5. Nelly— Country Grammar. Nelly brought out the whole neighborhood in St. Louis in this video. There weren’t any Rolls-Royces or yachts. It was hundreds of people dancing at a block party with Cadillacs and St. Louis BBQ. They looked like they were having more fun with nothing fancy at all. This was the American neighborhood party I wanted to be at. It was the hip-hop party I could relate to.

Another BET show that absolutely fascinated me was Comicview . It was an “urban” stand-up comedy showcase with “urban” stand-up comedians performing in front of an “urban” audience, talking about “urban” stereotypes. This was my first exposure to stand-up comedy. It was more than just funny to me; it was unrestrained, dynamic and culturally relevant. I couldn’t really understand what the comedians were saying and I was lost on the stereotypes they were referring to. It was like a whole new language to me. I had no concept of the credit system in America, let alone the stereotype of black people having bad credit; I didn’t understand why white people were always doing crazy things, like skydiving and hiking, that black people would never do; and I didn’t understand what it meant when a comedian said, “Mama trippin’.” Did his mom trip and fall over on the floor? Is she okay? Even though I couldn’t understand half of the bits, I was enthralled by the performances. Comicview was a slice of real American culture that I’d never known before. I thought to myself, If I can understand Comicview, I will understand everything about America. So I watched BET Comicview religiously for three years. And I learned about this country from the realest American educators: comedians. They weren’t just telling jokes, they were making insightful observations from a unique point of view. Rap City taught me American English; Comicview enlightened me about American culture. These shows had such a huge influence on my life. I soon found my first love in making hip-hop music before I eventually became a stand-up comedian.

I couldn’t rap for shit, but I wanted so badly to be part of the glamorous rap game that I’d seen on Rap City. Chris downloaded a bootleg copy of Sony’s ACID Music Studio, a beat-making software, and he started cranking out some sick beats. Then Jeremy, Phil and I would go to Chris’s mom’s apartment and record our raps on his five-dollar computer microphone. Next thing you know, we’d formed a rap group just like N.W.A. Chris’s mom’s apartment and his Dell desktop became our recording studio. We felt like the real deal and we called ourselves Syndakit. The first time I recorded at Chris’s house, he played me a beat he had just made. It sounded like a real track I’d heard on Rap City. I pulled out my trigonometry notebook and I was ready to write my first rhymes, but I had no idea where to start.

“So… what do I write?”

“Just write anything you want.” Chris was the Dr. Dre to my Eazy-E.

“How much do I write?”

“I think you need sixteen bars.”

I understood that “bars” were some kind of quantifier for lyrics and not Snickers, but is a bar one word? Is it a full sentence? Or can it be a fragment? Chris saw the confusion on my face, and he explained:

“One bar is one line that is four beats.”

“Oh, yeah, totally, I got that.”

I had no idea what a beat was. This was like one of those stupid dictionary descriptions where they explain a word with the same word you don’t understand. Pathological — of or relating to pathology. If I knew what pathology meant I wouldn’t have asked for the definition of pathology! But I went with it. I flipped past the trigonometry homework in my notebook, and started writing down my first sixteen bars.

Don’t hate the player ’cause the player don’t play, haters talk shit but the bullet stays.

And those were the first two bars I ever wrote. It was two uninspired, fraudulent lines copied from what I’d heard on BET. What bullet? I was an A student in Beverly Hills High School. I should have been rapping about the Pythagorean theorem. But I wanted to be a gangsta-ass rapper, so I rapped about sex, drugs and gangbanging. In reality, I was a virgin who had a seven o’clock curfew. I scribbled down another fourteen bars of garbage and I was ready to make my first gangsta rap song. Chris held up the five-dollar computer mic and I started spitting my sixteen bars. Two seconds in, Chris stopped me.

“What happened?” I was curious as to why he had stopped my incredible flow.

“You’re not on beat.”

“What do you mean I’m not on beat?”

I wasn’t challenging him; I actually didn’t know what being on beat meant.

“Jimmy, you have to rap to the rhythm of the music.”

I had no idea that I was supposed to be matching the rhythm of the music. I was literally just talking over the music. When Chris played me the beat again, I mechanically bobbed my head to the kicks and snares, but I couldn’t follow the tempo. And that’s when I realized that this was exactly what the Comicview comedians meant when they said, “White people got no rhythm.” This Chinese boy got no rhythm.

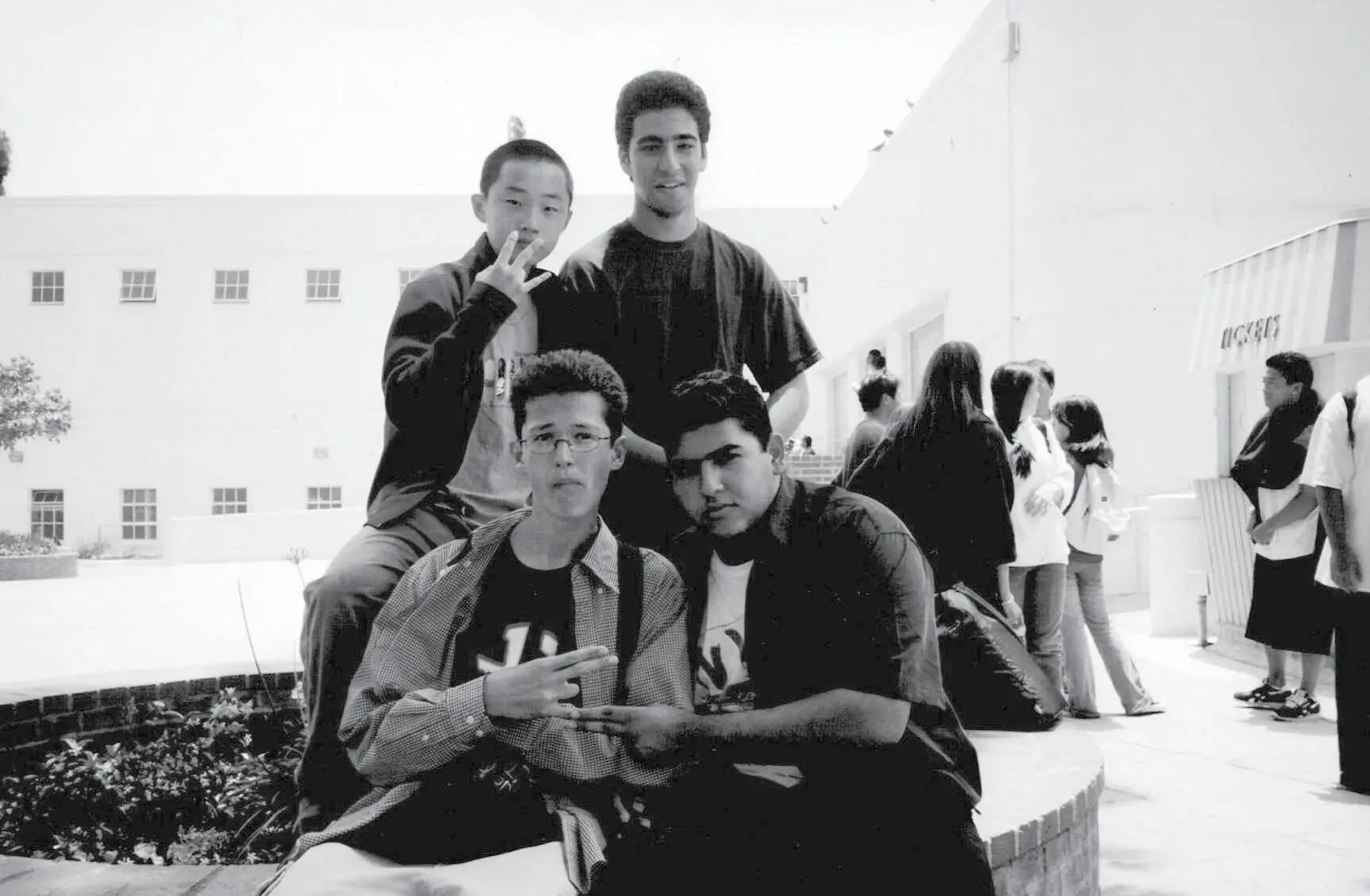

When the other kids were busy chasing girls and scoring booze, we went to Chris’s house to make music. The thought of maybe getting on BET Rap City one day gave us something to strive for, but more importantly, making music gave us an identity. We weren’t the random kids who hung out by the cafeteria anymore; we were now the kids who made hip-hop. We made a full-length rap album with that five-dollar microphone and we pushed those CDs to everyone we knew in class. We’d burn the CDs and each carry a Walkman in class, showing people the songs. “Hey, check out our tracks, get it before we blow up. We gonna go platinum, homie.” That was my sales pitch. I think we ended up selling three copies of the album for a total proceed of fifteen dollars, so technically we were only 499,997 records away from going platinum. We made just enough money to recoup for the five-dollar computer mic and a ten-dollar stack of CD-ROMs.

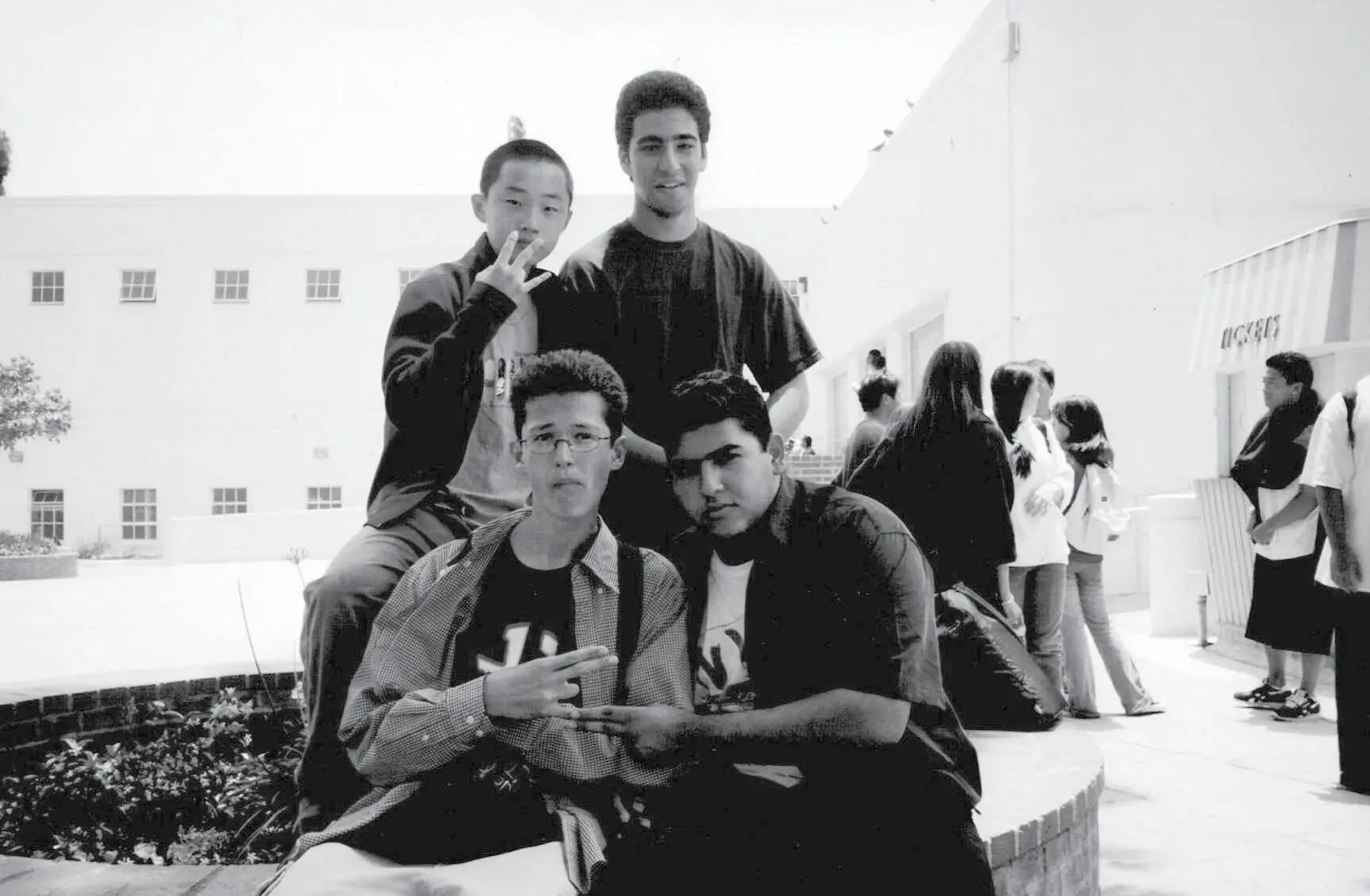

The Syndakit gang. Jeremy (top right), Phil (bottom right), Chris (bottom left). Throwing up random gang signs that we’d seen on BET. Needless to say, I never got laid in high school.

We even performed at the battle of the bands in our high school wearing ridiculous iron-on matching Syndakit T-shirts. Most people thought we were completely ridiculous, and rightfully so, but it was the first time anyone even noticed us. A skinny half-white guy, two Persian dudes and a Chinese immigrant rapping about gangster shit. We looked more like a sketch comedy group than a rap group.

Chris decided to take music more seriously, so he recruited two other friends from our school to our rap group who could actually rap: Yuji, a half-black, half-Japanese dude who acted like two black dudes, and Julian, a quietly cool black dude who was a great rapper. Jeremy, Phil and I would eventually get fazed out of Chris’s songs, and rightfully so; we sucked. So I took matters into my own hands and downloaded a bootleg beat-making program called Fruity Loops and started to make my own beats. I came up with a producer name, Doc West. An uninspired attempt to combine my two favorite hip-hop producers’ names, Dr. Dre and Kanye West. I sat in front of my computer for four hours a day in an attempt to come up with something decent. Then in an ultimate coup d’état, I recruited Julian and Yuji to join my own rap group. The three of us would be a perfect balance of 1.5 Asian guys and 1.5 black guys. I named our rap group the

Читать дальше