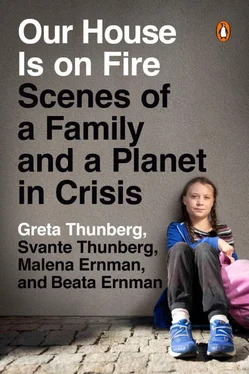

Greta Thunberg - Our House Is on Fire - Scenes of a Family and a Planet in Crisis

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Greta Thunberg - Our House Is on Fire - Scenes of a Family and a Planet in Crisis» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 2020, ISBN: 2020, Издательство: Penguin Books, Жанр: Биографии и Мемуары, Публицистика, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Our House Is on Fire: Scenes of a Family and a Planet in Crisis

- Автор:

- Издательство:Penguin Books

- Жанр:

- Год:2020

- Город:New York

- ISBN:978-0-14313-357-5

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Our House Is on Fire: Scenes of a Family and a Planet in Crisis: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Our House Is on Fire: Scenes of a Family and a Planet in Crisis»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Our House Is on Fire: Scenes of a Family and a Planet in Crisis — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Our House Is on Fire: Scenes of a Family and a Planet in Crisis», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

On the way to work.

At the supermarket.

At the shopping centre.

Or on the way to a TV recording in Tokyo.

Some of them are going to hover around up there for a thousand years.

Some will be bound up in trees and plants.

And some may be vacuumed up and stored deep down in the bedrock by means of some invention and some smart logistics that haven’t been created yet.

Perhaps a magic vacuum cleaner will be invented for the oceans too; a machine that can clean our oceans of all the CO 2that has been absorbed there. It will no doubt be needed, because up to 40 per cent of our CO 2emissions are soaked up by the oceans and cause acidification that many consider to be an even greater threat than the greenhouse effect taking place in the atmospheric layers above the surface.

So we will all live on for centuries – but perhaps not in the way we’ve imagined.

Because, with very few exceptions, the memory of our existence is not going to survive the ecological traces we’ve already left behind.

If these thoughts feel a little dark and hopeless right now, keep in mind that all it may take is a single big pop star or influencer to start redrawing this map. The power of celebrities is by all means controversial, but this is the reality we live in today and we don’t have time to change it. The advantage is that, in today’s connected world, it’s enough for just one king, superstar or pope to choose to strive towards zero emissions – with all the veganism, rejection of flying and solar panels on the roof that entails – for change to feel more possible.

No one can create a change in our whole system on their own. But one single voice could be enough to start a chain reaction that can set everything in motion – if that one voice is powerful enough.

IV

Imagine If Life Is for Real and Everything We Do Means Something

‘But man is a part of nature, and his war against nature is inevitably a war against himself.’

– Rachel Carson, Silent SpringSCENE 87.

Further North, July 2018

It’s hot in Luleå. Really hot. Svante wipes the sweat from his brow, flaps his shirt to air it and exhales loudly and demonstratively. But the woman at the reception desk wants no part of that kind of wordless comment.

‘Now that it’s finally really warm up here I don’t want to hear anyone complaining,’ she says, as if this was about a topic of greater importance than some old weather.

‘Of course,’ he replies, entering the code on the card reader. It’s important to pick your battles.

Greta and Roxy are waiting on the street outside the hotel and together she and Svante drag the luggage to the electric car and open the boot. Svante hoists up the suitcase next to the microwave oven, induction hob and all the groceries Greta can conceivably need during the coming two weeks. Then Roxy jumps in and settles down, Greta feeds the destination into the satnav, and they drive out of the car park.

‘The battery range is twenty kilometres short,’ Greta says while they slowly and almost soundlessly roll towards the highway.

‘Today we’ll just drive on the battery,’ Svante says. ‘Slowly. We’ll minimize electricity consumption and see how far we get.’

They drive on towards Kalix and turn north towards Gällivare.

The summer landscape zips past the car window at 80 kilometres an hour. The forest looks different to them now. A few years back they saw trees and nature and untouched fields. Now they see clear-cutting, plantations and monocultures that have deprived the soil of its diversity and resistance.

Greta would have preferred to take the train, because no personal vehicle in the world can be considered sustainable, however electric it may be. But it’s still an impossibility because of her eating disorders and compulsions, and the simple fact of being able to travel like this is such enormous progress that would have been unthinkable even a few months ago. Greta’s energy has increased a little every day since last spring. Since the writing contest in the newspaper Svenska Dagbladet . Since she started planning her school strike.

Farms are sunk in 27°C summer heat. Abandoned farms. Working farms. Farms with livestock and people.

Farms with heaps of broken-down motor vehicles. Cars, tractors, campers, snowmobiles, snow-blowers, mopeds and motorcycles. Every other driveway is a potential motor museum.

But in some places, just beyond the road, you can still sense the dream of a different, simpler and perhaps better life. Small red houses rise out of the scraggy earth and give shape to the silhouette of an era that almost seems to have been frozen in time.

They are listening to This Changes Everything by Naomi Klein. Periodically they pause the audiobook to talk about what she’s saying. Then they back up and listen again.

Play, listen, pause.

The bushes, thickets and the green pine forest extend almost all the way up to the Arctic Circle and an exotic white road sign announces that you are crossing the ‘cultivation boundary’. The road is almost perfectly straight and deserted. Mile after monotonous mile. Scrawny trees that slowly shrink in size the further from the Gulf of Bothnia they get.

Some kind of black, long leaves are hanging from the pines; they don’t know what they are. Greta takes some pictures and says that they can ask someone tomorrow when they arrive.

Driving conditions are perfect for the electric car and the battery’s range gets longer and longer relative to the destination.

‘But we’ll stop and charge in Kiruna anyway. We have to buy bread and vegetables, don’t we?’

‘Mmm,’ Greta answers.

At the Co-op in Kiruna a sign boasts of ‘Steps Forward for the Climate’. So far it consists of two electric-car chargers in one corner of the enormous car park at the Kiruna shopping centre. One of them is broken and plaintively blinking red, but the other one works and Svante politely asks the person idling there in an SUV if they can wait at one of the other vacant spots so he can get out of the car and plug it in. The car charges at 50 kilometres an hour and they walk slowly across the crowded car park towards a grove where Roxy gets to run off some energy and sniff the surroundings. She is far from County Cork and the backyard where she grew up.

It’s hot in Kiruna too. Just as hot as in Luleå. It reeks of exhaust, frying oil and freshly cut grass. A man comes out of the DIY store with a hedge-trimmer under one arm. He is wearing cut-off jeans and a white T-shirt, and under his other arm he is carrying an empty box, which he sets down right outside the shop door. He is ready to go out into the neighbourhood and give the Arctic vegetation what it deserves.

They use the toilets at Burger King, squeezing through overflowing trays, chairs and tables loaded with Whoppers, Coca-Colas and French fries. The floor is sticky with ketchup and spilled soft drinks.

Men in hiking gear are standing outside the state off-licence with beer crates, fishing rods and backpacks spread out on the pavement in front of them. In anticipation of being in the wilderness they have transformed their little corner of the shopping centre into a men’s changing room – they swear, spit and laugh loudly. It’s fishing time. Time for the great outdoors. And time to drink.

Greta and Svante buy what needs to be bought and then drive on. The radio is playing Beata’s favourite song, ‘Whatever It Takes’ by Imagine Dragons, and Svante misses her so much it hurts.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Our House Is on Fire: Scenes of a Family and a Planet in Crisis»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Our House Is on Fire: Scenes of a Family and a Planet in Crisis» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Our House Is on Fire: Scenes of a Family and a Planet in Crisis» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.

![Корнелл Вулрич - Murder at Mother’s Knee [= Something That Happened in Our House]](/books/398097/kornell-vulrich-murder-at-mother-s-knee-somethin-thumb.webp)