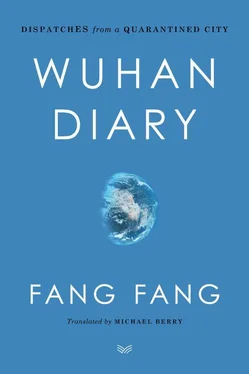

Fearful of being censored, it seems as if I am turning into someone who only reports the good news but ignores the bad. In actuality, these bits of good news are things that I genuinely want to share with my readers. We have been yearning for some good news for so long. Online, there are all kinds of discussions and scary controversies that people are sharing; there are also all these experts trying to analyze everything logically, and then there are all those ridiculous rumors floating around. For those of us here in Wuhan, we really don’t want to hear about any of that stuff. All we worry about is ourselves; we worry about whether or not the number of infected patients has declined, whether or not people who need to be admitted can get a bed in the hospital, whether or not they have received effective treatment, whether or not the number of fatalities has decreased, when will the next food delivery come, and when we can finally leave our apartments.

The bad news continues to worry me. This afternoon Professor Lin Zhengbin, an organ transplant specialist from Tongji Hospital, passed away. He was 62 years old, full of energy, and had an incredible wealth of experience in his field; it is such a terrible shame to lose him. Tongji Hospital is connected to Huazhong University of Science and Technology. They have lost two top professors in just three days; everyone on campus is quite heartbroken. I also heard that Central Hospital—that is where Li Wenliang worked in the ophthalmology department—now has two more doctors whose conditions have deteriorated to the point that they both had to have breathing tubes inserted. Even worse, because of lingering anger over the death of Li Wenliang, I heard that some donations have come with stipulations not to give any supplies to Central Hospital because of the way they treated Dr. Li. (I’m not sure of the accuracy of this yet.) Right now Central Hospital is in desperate need of more supplies. My goodness, if Li Wenliang were able to hear this news, he would be more upset than anyone else.

February 11, 2020

The arrival of a new life is the best hope that heaven can give us for the future.

The weather today is just like yesterday—still gloomy, but not quite as overcast.

This afternoon I saw a photograph of some of the donations coming in from Japan, and the boxes had a couplet from an old classical Chinese poem printed on them: “A mountain may separate us, yet we share the same clouds and rain; The bright moon belongs to both my village and yours.” [12] These lines are taken from Wang Changling’s poem “Seeing Off Imperial Censor Chai” (“Song Chai shiyu”), which dates from the Tang Dynasty.

I was so moved to see that. I also saw a clip of Joaquin Phoenix’s Oscar acceptance speech where he seemed to be fighting back tears to say how he wanted to use “the opportunity to use our voice for the voiceless,” which also really touched me. I also read a line from Victor Hugo today: “It is not so easy to keep silent when the silence is a lie.” But this time I wasn’t moved; instead I felt a sense of shame.

That’s right; I have no choice but to go with shame.

There are even more videos out there filled with people crying out for help that make you want to scream; but I can’t stand watching them anymore. I know that no matter how rational I may be, I too have my breaking point. And those people who might be somewhat less rational than me are even more prone to losing it. Right now, the single most pressing thing for us to do is to raise up our heads and look toward wherever we might find a glimmer of hope. I hope we can look toward those people who continue to move forward even in the face of danger, like those who built the Huoshenshan and Leishenshan Hospitals. I hope we can look toward those people who continue to do their best even when they themselves are struggling, like those people with so little to their name yet who commit to leaving their life savings to help the poor (I also approve of those appeals not to accept their money). I hope we can look toward those people who stand by their post even when they are on the brink of exhaustion, such as those medical professionals who continue working even with the threat that they themselves might get infected. And I look to those people out there day and night in the streets volunteering to help with all kinds of tasks that need to be done. And then there are so many more…. Looking at what they do helps me understand that, no matter what, we cannot be scared and we cannot fall apart. If that happens, everything we have fought for will be for nothing. So no matter how many heartbreaking videos you see and no matter how many terrifying rumors you hear, you must not be afraid and you must not break down. The only thing we can do is to protect ourselves and take care of our families. We need to follow instructions and cooperate completely with whatever is asked of us. Just shut the door, grin and bear it. No one will blame you if you want to have a good cry to just let it out or even stop following the news about the outbreak. Watch some TV or put on a movie, watch some of those lousy variety shows, do whatever you have to do to get through this. Perhaps that is our contribution.

Things are gradually starting to take a turn for the better, even though everyone knows it will still take some time, but isn’t a slight improvement already a form of hope? Besides Hubei, almost all other provinces in China have begun to see a marked improvement. But now with the help of so many people, Hubei is also headed in the right direction. Just today quite a few patients were discharged from the temporary hospitals. Some of those who have recovered had smiles on their faces as they left the hospital; you could tell they weren’t just hamming it up for the media, those were smiles of genuine happiness. It wasn’t that long ago that you would often see people smiling like that on the street, but it has now been a long time since I have seen that. But I figure this is just the beginning; perhaps before too long we will see the streets filled with smiling faces again?

Now that I mention it, I have been living here in this city of Wuhan for more than 60 years. This city has been my home ever since my parents brought me here from Nanjing when I was two years old, and I have never left. I went to kindergarten here, elementary school, middle school, high school, university, and even stayed here to work after graduating. I have worked here in this city as a porter (I worked at Baibuting!), a reporter, an editor, and a writer. I lived in Hankou, just north of the river, for more than 30 years and south of the river in Wuchang for another 30 years. I lived in Jiang’an District, I went to school in Hongshan District, I worked in Jianghan District, eventually settled down in Wuchang District, and spent a lot of time writing in Jiangxia District. In the 30-odd years since I graduated from college, I attended countless conferences in a variety of capacities. My neighbors, classmates, colleagues, and fellow writers are spread out deep in every corner of this city. When I’m out I run into people I know all the time. There was a girl writing an online diary who was crying out for someone to save her father; I suddenly realized that I actually know her father, he is a fellow writer. I once met him back in the 1980s at a television station. For the past few days I’ve been having trouble getting the image of her father out of my head. If it hadn’t been for his death, I probably would have never remembered him. I’m always saying that all my memories are deeply rooted in this city, each memory planted by the people I met in this city from my childhood all the way into my old age. I’m a Wuhan native, through and through. Two days ago an internet friend of mine sent me an instant message with a short essay attached. Contained in that document were words that I had completely erased from my mind. One year sometime during the last century, Chen Xiaoqing hosted a documentary series on CCTV called One Person, One City ; [13] One Person, One City ( Yigeren he yizuo chengshi ) was a 2002 CCTV documentary series directed by Wei Dajun and written by Li Hui and Feng Jicai. The series contained 17 episodes to approach various cities in China through the personal lens of famous writers; including Liu Xinwu (Beijing), Sun Ganlu (Shanghai), and Zhang Xianliang (Yinchuan). The episode on Wuhan featured Fang Fang.

I wrote the script for the episode on Wuhan. I wrote: “Sometimes I ask myself, compared to other cities in the world, why is Wuhan such a difficult place to live? Perhaps it has to do with the terrible weather here? Then what is it that I like about this city? Is it the city’s history and culture? Or is it the local sites and customs? Or is it the natural scenery? Actually, it is none of that. The reason I like Wuhan starts with the fact that this is the place I am most familiar with. If you line up all the cities in the world before me, Wuhan is the only place I really know. It is like a crowd of people walking toward you and amid that sea of unfamiliar faces you catch sight of a single face flashing you a smile that you recognize. To me, that face is Wuhan.” I remember when that episode first aired, the painter Tang Xiaohe [14] Tang Xiaohe (b. 1941) was born in Wuchang and is regarded as one of China’s leading oil painters active during the Mao period. Many of his revolutionary-themed paintings were widely reprinted and circulated as posters and murals; many of his works have been included in the collection of the China Art Gallery.

called me to tell me how much he admired those lines I wrote for the show’s narration. That’s because Mr. Tang and his wife, Mrs. Cheng Li, understood exactly what I was trying to say; the two of them have lived in this city even longer than me; they are true Wuhan natives.

Читать дальше

![О Генри - Закупщик из Кактус-Сити [The Buyer from Cactus City]](/books/405348/o-genri-zakupchik-iz-kaktus-thumb.webp)