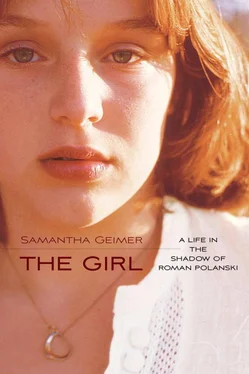

There were just two people involved in my rape in March 1977—the perpetrator Roman Polanski and me. I played my part—I was the kid who was raped. Polanski played his—he assaulted me, and was arrested and charged. And that should have been that. Still, even though I was only thirteen years old, I just knew this was turning into something far bigger than what happened that night. And somehow, what had happened, as bad as it was, was not going to be as bad as what was coming.

I hoped I was wrong. I must have been wrong, right?

Then I ran into the two-headed monster of the California criminal justice system, and its corrupt players whose lust for publicity overwhelmed their concerns with justice. To be fair, there are those who sincerely believe that laws must be enforced regardless of the consequences to the victims. For me, the consequences of the rape laws being vigorously pursued against Polanski would have meant I would be exposed to aggressive, damaging, and adversarial examination by Polanski’s lawyers, who would make the case that either it never happened, or that I was some trampy thirteen-year-old temptress and so it wasn’t that big a deal. My case would be tried not only in the court, but also in the media. All the stories about me would be salivated over again. My crime? Being the rape victim of a Hollywood celebrity. I realize that there are people who, in the pursuit of attention and notoriety, feel no shame. After all, the fame of both Kim Kardashian and Paris Hilton rests not on singing or dancing or acting, but on their ability to make a hot sex tape. I admire them for making the best of an uncomfortable situation, and if they can take the heat, then good for them. But it’s not as easy as it looks.

• • •

Larry and my family agreed that protecting the victim—me—was more important than Polanski being prosecuted to the full extent of the law. We were forced to fight to allow him to plead to the least serious of the charges to avoid my being splashed across every tabloid in the nation. And then we had to fight again, recently, when without any consultation with me whatsoever, efforts were renewed to have Polanski extradited to the United States. And by the way, even in 1977 it wasn’t a difficult decision. My family never asked that Polanski be punished. We just wanted the legal machinery to stop.

I was a young girl during the circus surrounding the rape in the late 1970s, and depended on the care of my parents and attorney. Now, thirty-five years later, I have my own judgment, developed over a long period of reflection, to guide me. Polanski made a horrible mistake and compounded it by fleeing the country. On the other hand, he has been publicly exposed as a rapist, his career has been damaged, and he has lived as an exile from the United States, the center of the movie universe. Enough punishment? There’s disagreement on the answer to that. But to me it’s the wrong question. I’m not interested in punishment; I’m interested in justice. And justice, I believe, starts with the interests of the victims—particularly when it is clear that the perpetrator is not a threat to the rest of society.

The brouhaha around Polanski’s extradition has become ever more curious. There’s simply no doubt that Judge Rittenband, the original presiding judge, was a shameless publicity seeker. DA David Wells has admitted to lying. Yet it appears that none of this will be investigated until Polanski surrenders.

I don’t think that is the way our system is intended to work. We have a Department of Justice, not a Department of Punishment. We have Lady Justice, not Lady Punishment. She is holding scales; I believe these indicate balance. Not a balance between the rights of the victim and publicity for the judge. Not a balance between the rights of the victim and a license to lie by the DA. Not a balance between the rights of the victim and the ambition of a public servant. If there’s to be any balance at all, it has to be between the rights of the victim (to end their suffering) and the interests of the state (to punish the crime), with the emphasis on protecting the innocent.

How can the state of California refuse to investigate the misconduct of a judge and a prosecutor, because a celebrity has broken the law? Shouldn’t officials of the court be held to a higher standard? I call for the investigation of what happened behind closed courthouse doors in 1977 and 1978. As a victim, the California Victims’ Bill of Rights provides me some consideration. But the district attorney’s office refuses to extend any. Instead they unconscionably withhold those rights. They treat my rights as privileges that must be earned. And I earn them only by submitting. I must follow their unwritten rules, while they don’t even follow their own laws. The offense they suffered at Polanski’s flight supersedes all else. My rights as a citizen and a victim, the misconduct of court officials, those are set aside, because the rule of law must apply to Polanski first. Why? Justice applied selectively, applied at the whim of the district attorney’s office. Why?

Punishing Polanski for what he did to me was only one motivation in many, and a relatively minor one at that. There were much more pressing concerns: politics, business, spectacle.

The analogy that always comes to mind when I think of the way I was treated is this: What if, instead of being raped, I were injured in a different way? Say I have a really bad cut on my arm that is covered by a bandage and that is just barely starting to heal. Would it be appropriate for anyone to say to me: Wow, will you tell me all about how that happened? Can you take the bandage off so I can look at it? It’s stopped bleeding, can you squeeze it a little so it starts to bleed again? Does it hurt worse now? That’s what it feels like to me, anyway.

The Polanski case was not a good, or even bad, example of justice. It was in some ways the opposite of justice. Justice is not intended for entertainment or the enrichment of public officials, pundits, and media corporations. I do not believe that punishment and spectacle can be substituted for justice. I do not believe that rules and laws for the sake of themselves are more important than justice. I do not believe that rules and laws applied in a vacuum for the sake of supporting a narrow point of view represent justice.

Because I am demanding justice for the victim, it would be hypocritical if I didn’t also demand justice for the defendant. Justice equals fairness for all concerned. Polanski and I are human beings, not political footballs, and neither of us should be misused by the system. It may seem odd that I’m campaigning for justice for Roman Polanski, the man who was, for that sliver of time, so selfish and self-serving. But it’s more bizarre to me that the system is such that, in this case anyway, the only way to get justice for the victim is to ask for relief from punishment for the criminal. It’s not perfect. But it’s right.

• • •

In April 2013, the London Feminist Collective staged a protest of a retrospective of Polanski’s films at the British Film Institute (BFI). Women marched with placards that said things like “Polanski’s Still on the Run/But That Don’t Bother the BFI None” and ran side-by-side photos of Polanski with Jimmy Savile, the knighted British entertainer, now deceased, who was recently found to have sexually molested hundreds of children. (Placard: “Would you run a Savile season?”) The Collective released a press statement that said, in part: “The British Film Institute has joined in with the minimization of Polanski’s crime by running a retrospective of his work without ever mentioning the fact that he is also a convicted child rapist [ sic ]…. The ‘he’s an artiste’ defense arises every time these issues are raised and it remains utter garbage. Being an ‘artiste’ has never been an acceptable excuse for an adult male to abuse a child and it never should be.”

Читать дальше