I wrote to the magazine, enumerating some of the fabrications—that my mother did not sleep with Polanski, I did not have a “love bite” on my neck when Polanski met me, Polanski did not choose my clothes while I stood there in panties and bra—and of course, the fact that I was not exchanging trips to Disneyland for access. The Molly Brown allusion is the most baffling. If I, like Molly Brown, were a relentless social climber, I must have been the worst social climber in history, leaving Los Angeles to live quietly and happily and anonymously on a remote island.

I was not the only one to take exception to this piece. Polanski weighed in—objecting, among other things, to being called an “exile” from the United States when in fact he is and always was a French citizen. And Anjelica Huston’s note rather hilariously and succinctly sums up how much the author had gone off the rails. “I would like to set the record straight. At no point have I ever described Roman Polanski as a freak, nor have I ever seen him in the nude.”

Vanity Fair issued a snotty non-apology: “We apologize for any possible misunderstanding, but have no reason to believe that one did occur.”

(Several years later, Polanski sued and won an $84,000 judgment against Vanity Fair for a 2002 article on Elaine’s restaurant where the writer claimed that Polanski had stopped by the watering hole and tried to pick up a hot blonde on the way to his wife’s funeral. Polanski was nowhere near the restaurant at the time. Oops!)

The most upsetting part of the story wasn’t the lies. It was the version of the truth they dredged up and published—the intimate sexual questions and answers from the original grand jury testimony when I was thirteen years old. Good work, Robinson. Nice move, Vanity Fair . Bet it sold a lot of magazines.

• • •

By the late 1990s I had finally decided to come out of hiding: I did an interview with Inside Edition where I revealed my identity. This was a relief, even if it did cause a flood of ancillary articles—particularly whenever Polanski, who now had a beautiful young wife, two little children and a flourishing film career in Europe, attempted again to broker a return to the United States without being arrested and thrown in jail. But I was tired of hiding and being afraid, tired of people making up lies about me. So I figured I’d say here I am. If you have a question, ask it. If you have something to say, don’t think I won’t say something back.

The whole issue flared in 2003 when Polanski was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Director for his 2002 film, The Pianist . This partly autobiographical movie about a Polish-Jewish musician struggling to survive the destruction of the Warsaw Ghetto during World War II was by all accounts extraordinary (I haven’t seen it; as you can imagine, I’m not exactly sitting around waiting for the next Polanski release). But there was, predictably, outrage in certain quarters that a child rapist and fugitive would be nominated for best director. Never mind the absurdity of asking me whether Polanski should win an Oscar for a movie I’d never seen; this time, with the onslaught of calls and instructions to my children not to answer the phone, there was a great deal of upset for my children: Oh, something bad happened to Mom. Oh, now we’re all a part of it. Mom is damaged.

(The controversy had its own life, of course, but it might have been fueled by the not-dissimilar incident a few years earlier involving Woody Allen, who was found to be having an affair with the adopted daughter of his lover Mia Farrow. Mia Farrow then accused him of molesting the daughter they adopted together. He was vilified, but that didn’t keep him from being nominated for six Academy Awards as a director and a screenwriter in the years following.)

The question is this: Should a man’s personal life dictate the way we judge his work? I gave my own answer in an op-ed piece I wrote for the Los Angeles Times in February 2003, right before the Oscars. It was titled “Judge the Movie, Not the Man.”

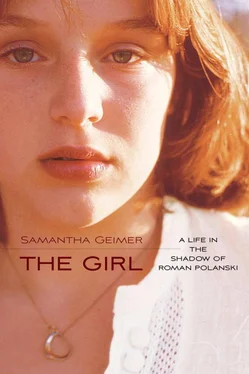

I met Roman Polanski in 1977, when I was 13 years old. I was in ninth grade that year, when he told my mother that he wanted to shoot pictures of me for a French magazine. That’s what he said, but instead, after shooting pictures of me at Jack Nicholson’s house on Mulholland Drive, he did something quite different. He gave me champagne and a piece of a Quaalude. And then he took advantage of me.

It was not consensual sex by any means. I said no, repeatedly, but he wouldn’t take no for an answer. I was alone and I didn’t know what to do. It was scary and, looking back, very creepy. Those may sound like kindergarten words, but that’s the way it feels to me. It was a very long time ago, and it is hard to remember exactly the way everything happened. But I’ve had to repeat the story so many times, I know it by heart.

We pressed charges, and he pleaded guilty. A plea bargain was agreed to by his lawyer, my lawyer and the district attorney, and it was approved by the judge. But to our amazement, at the last minute the judge went back on his word and refused to honor the deal.

Worried that he was going to have to spend 50 years in prison—rather than just time already served—Mr. Polanski fled the country. He’s never been back, and I haven’t seen him or spoken to him since.

Looking back, there can be no question that he did something awful. It was a terrible thing to do to a young girl. But it was also 25 years ago—26 years next month. And, honestly, the publicity surrounding it was so traumatic that what he did to me seemed to pale in comparison.

Now that he’s been nominated for an Academy Award, it’s all being reopened. I’m being asked: Should he be given the award? Should he be rewarded for his behavior? Should he be allowed back into the United States after fleeing 25 years ago?

Here’s the way I feel about it: I don’t really have any hard feelings toward him, or any sympathy, either. He is a stranger to me.

But I believe that Mr. Polanski and his film should be honored according to the quality of the work. What he does for a living and how good he is at it have nothing to do with me or what he did to me. I don’t think it would be fair to take past events into consideration. I think that the academy members should vote for the movies they feel deserve it. Not for people they feel are popular.

And should he come back? I have to imagine he would rather not be a fugitive and be able to travel freely. Personally, I would like to see that happen. He never should have been put in the position that led him to flee. He should have received a sentence of time served 25 years ago, just as we all agreed. At that time, my lawyer, Lawrence Silver, wrote to the judge that the plea agreement should be accepted and that that guilty plea would be sufficient contrition to satisfy us. I have not changed my mind.

I know there is a price to pay for running. But who wouldn’t think about running when facing a 50-year sentence from a judge who was clearly more interested in his own reputation than a fair judgment or even the well-being of the victim?

If he could resolve his problems, I’d be happy. I hope that would mean I’d never have to talk about this again. Sometimes I feel like we both got a life sentence.

My attitude surprises many people. That’s because they didn’t go through it all; they don’t know everything that I know. People don’t understand that the judge went back on his word. They don’t know how unfairly we were all treated by the press. Talk about feeling violated! The media made that year a living hell, and I’ve been trying to put it behind me ever since.

Today, I am very happy with my life. I have three sons and a husband. I live in a beautiful place and I enjoy my work. What more could I ask for? No one needs to worry about me.

Читать дальше