While Polanski protested that the photo had been cropped, and in fact all the women surrounding him were also surrounded by their husbands and boyfriends, it was too late. Rittenband was seething. He was being played the fool, he said, and told a reporter from the Los Angeles Herald Examiner that “Roman Polanski could be on his way to prison this weekend,” adding, “I didn’t know when I let him go that the movie would be impossible to finish in 90 days. I do feel that I have very possibly been imposed upon.”

Polanski, at Judge Rittenband’s orders, returned, and when he did, the judge gave him the ninety days for that diagnostic study. Predictably, this was all accompanied by another media scramble and more debate about whether Polanski was getting his just rewards or was the victim of persecution. Judge Rittenband angrily let it be known to the lawyers that he alone held Polanski’s fate in his hands, that he still had the power to put him away for fifty years.

On December 16—after a farewell bash attended by Tony Richardson, Jack Nicholson, and Kenneth Tynan, among others—Polanski was escorted through a phalanx of photographers and reporters to the state prison by his entertainment lawyer, Wally Wolf, and Hercules Bellville, his friend and second unit director on several of his films. Polanski believed Judge Rittenband, in a fit of pique, tipped the media off as to the date and time of his arrival.

Years later, in his autobiography, Polanski claimed he actually found a certain contentment in jail, and while various stories leaked into the rags courtesy of other on-the-take inmates (including a story that he’d promised a prisoner’s four-year-old daughter a part in his next movie, with a sinister insinuation of his love for the very young), the time he passed there was relatively trouble-free. “I felt secure and at peace,” he wrote.

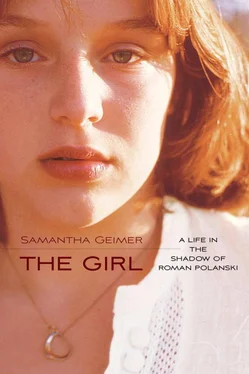

At the beginning of tenth grade, everything was wrong. Everything. First and most important, I was back in California, back where I was The Girl, missing my friends and boyfriend back in York. I was in a new high school where I knew virtually no one, since my junior high friends had dispersed to other schools. I wasn’t friends with the popular girls, whom we called the Guccis. (The designer of the moment; you had to have those jeans, plus the gold chains and hoop earrings, or you were nothing.) I cut my hair short and gained some weight; I told myself I wanted a different look—and I did—but I also had some ideas about looking tougher. It had always been easy for me to get good grades, but now the grades meant nothing. I became cozy with the stoners—a low-pressure group of kids who never asked me any questions, partially because they didn’t know about what had happened over the past year, but also because they didn’t care. In some sense we were losing ourselves in drugs, but still finding great solace in each other. My mother was constantly worried about me, but felt powerless to help. As she told me many years later, her attitude toward me at the time was “What can I do for you? Can I give you more? How can I make you happy?” It was total, total, guilt.

I don’t think this escalation of acting out was a conscious choice, but I was angry at the world and, with any thoughts of becoming an actress dashed, I didn’t want to be a cute little child anymore.

Not that I had to worry there. Before we learned there wouldn’t be a trial, my mother was very worried: I had grown and looked a lot older in the course of the year, and she felt that while I looked younger than thirteen at the time of the assault I really could now be mistaken for a teenager who was at least sixteen or seventeen. This would make the press even more hostile and would make it more believable that Polanski assumed I was of age.

I became more easily upset about everything, and spent a great deal of time crying in my bedroom. I didn’t want to be in California, I didn’t want to be in school… I just wanted to get off this train to Crazytown.

When my mother told me Polanski was locked up in jail undergoing psychiatric evaluation, I didn’t feel the slightest sense of satisfaction or justice served. To the contrary. I wished no one had ever found out. I continually kept second-guessing myself about that night. Why didn’t I put up more of a fight? Why did I drink? Why did I take the Quaalude? I felt certain I could have made him stop. I know it wasn’t rational but I felt responsible for it all. After months of this I came to see that blaming myself was wrong and useless, so I decided to sort of put these feelings aside, lock them in a box. When Mom told me about Polanski, I nodded and just walked away.

I was determined to get on with life. But it would become a life of “look away.”

• • •

Polanski was released from Chino State Prison on January 29, 1978, after having served forty-two days. The psychiatric report from Chino was, if anything, even more flattering than the original probation report. I’m sure he was an exemplary prisoner. Yet it’s pretty clear the prison officials were no more immune to the power of celebrity than the average groupie.

Philip S. Wagner, Chino’s chief psychiatrist, portrayed prisoner Polanski as more the victim than the violator. “There was no evidence that the offense was in any way characterized by destructive or insensitive attitude toward the victim,” he wrote. “Polanski’s attitude was undoubtedly seductive, but considerate. The relationship with his victim developed from an attitude of professional, to playful mutual eroticism…. Polanski seems to have been unaware at the time that he was involving himself in a criminal offense, an isolated instance of naiveté, unusual in a mature, sophisticated man.”

It’s not that I disagreed with much of that statement… but “ mutual eroticism”? “Isolated instance of naiveté”? Please.

When officials at Chino released Polanski less than halfway through his ninety-day “sentence” and said the diagnostic study was complete, the press was not happy. And when the press was unhappy, so was Rittenband. He called the lawyers back to his chambers for one more wild ride.

Larry had no formal role in the ensuing negotiations, but he was there, as he would say, to bring a conscience to all the mayhem—to remind them that there was a girl whose entire life could be affected by their decisions. On January 31, 1978, the day before Roman was scheduled to return to Judge Rittenband’s courtroom, the lawyers answered the judge’s summons. As usual, Gunson and Dalton took the two seats in front of Rittenband’s desk, and Larry took his place at the side of the large desk, next to the judge.

Larry recalls that Judge Rittenband began angrily and pompously lecturing them about how he wouldn’t allow Polanski to make a mockery of the courts. When his intercom buzzed, Rittenband growled to his secretary that he had directed her not to interrupt him under any circumstances and now she was interrupting him.

“Sir,” she said, over the intercom, “Bill Farr is on the phone.”

William Farr was a youngish (now deceased) reporter for the Los Angeles Times, and he’d been following the case. Known among fellow journalists for his gutsiness—he had served jail time during the Manson trial for refusing to disclose a source in one of his articles on the family that revealed they were plotting to kill Elizabeth Taylor and Frank Sinatra—he was also apparently a confidant of Rittenband. When Farr called, the conversation between the judge and Gunson and Dalton halted. “Yes,” he said. “I’ll take the call.”

Gunson and Dalton whispered to one another so as not to interfere with Rittenband’s phone call. Larry (as he explained to me later) couldn’t take part in their conversation where he was seated, so short of leaving the room or putting his fingers in his ears, he couldn’t help but hear the conversation between Farr and Rittenband. It sounded to Larry that they were involved in some kind of high-level decision making—but how could that be? One person on the call was the judge who ruled over the case, and the other person was a reporter.

Читать дальше