Why would all this be happening now? True, the United States could have sought Polanski’s arrest and extradition worldwide at any time since 1978. But at that moment, we knew nothing. I never even realized Polanski could leave France; I had no idea he had a chalet in Switzerland and traveled, semi-covertly, in and out of several countries. At the moment all I could think was, Why would he do something so stupid? And why should I have to live through it all—again?

I called my lawyer, Larry Silver, who said, “I don’t know what this is about, either. Do nothing. I’ll find out.”

Something, or someone, had stirred up old wounds. Maybe Steven Cooley, the Republican district attorney of Los Angeles—who, not coincidentally, was running for state attorney general—felt he had to show everyone who was the big macher and push for resolution in this famously unresolved case.

I suddenly recalled how uncomfortable I’d felt for many years in California, and in Los Angeles in particular. Celebrity didn’t just count for a lot; to a certain segment of the population, it was everything. And wherever a celebrity was involved, all emotions loomed large. Adulation, yes. But retribution, too. I had this sense that the entire legal system was saying to Polanski, You think you’re better than us? Well, just wait.

The purpose of the legal system is to punish criminals, of course, and there were many ideas about what this meant for Polanski—had he been punished enough for what he did? Did he still deserve to be held accountable? Or had the punishment been bungled so stupendously that anything further was cruel and unusual? And then there was the other purpose of the judicial system: to protect victims and protect society from criminals. So what was the sense of arresting Polanski now? Did society need to be protected from him? Did I?

Over the years, I have had bad dreams about the legal morass, the publicity, the questioning in the courtroom. But I don’t think I ever dreamed about Roman or that night at Jack Nicholson’s house. That doesn’t mean it wasn’t terrible. It was. But its terribleness didn’t haunt me. Other aspects of that time did. When Roman was arrested in Switzerland, it wasn’t exactly déjà vu, but it reminded me of the sense of powerlessness I had experienced as a thirteen-year-old girl. With the passing years, it had come to seem less and less likely that Roman would ever return to the States. He would live and die a celebrated director in France, where he was beloved, and I would hold on to the anonymity I cherished. And if he were to return, I assumed it would be because he’d resolved his legal problems and come back voluntarily. How could he be arrested again, thirty-two years later?

In a blink everything had returned nearly to the way it was decades before. Roman was sitting in a jail cell, and I was being hounded by the press. It was just like all those many years ago when we first met Judge Rittenband, the man who oversaw the case: we were bound again by a legal system that valued the headlines it could generate more than the effect its actions had on individuals. His rights as a defendant, my rights as a victim, were being stomped into the ground.

As the case moved again through the courts and old atrocities were revisited, my lawyer, Larry Silver, again beseeched the court to finally make the whole thing go away.

“The victim is once again the victim,” he wrote. “Everyone claims that they are acting to vindicate justice, but Samantha sees no justice. Everyone insists that she owes them a story, but her story continues to be sad.

“She endures this life because a corrupt judge caused, understandably, Polanski to flee. No matter what his crime, Polanski was entitled to be treated fairly; he was not. The day Polanski fled was a sad day for American justice. Samantha should not be made to pay the price. She has been paying for a failed judicial and prosecutorial system.”

“This statement makes one more demand, one more request, one more plea: Leave her alone.”

• • •

Now listen: I am not naïve. If you write a book, you’re not asking to be left alone. You’re inviting people into your life. I know that. Welcome.

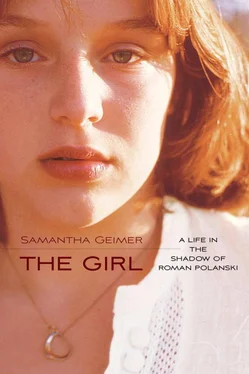

But I do have a reason. So much has been written about the Polanski case, but none of it has been written by me, the person at the center of it. So many years have gone by; it’s time. I’ve had so many years to rage, to laugh, to marvel at what people say and why they say it. In a sense I want to take back ownership of my own story from those who’ve commented on it, without rebuke, for so long. Because my story is not just pure awfulness. It’s crazy and sad, but yes, sometimes funny, too. It may have been messy at times, but it’s my mess and I’m taking it back.

There is even, as we parents say, a teachable moment. We have what I think of as a Victim Industry in this country, an industry populated by Nancy Grace and Dr. Phil and Gloria Allred and all those who make money by manufacturing outrage. I’ve been part of it. If you spent years reading about yourself in the papers with the moniker “Sex Victim Girl,” you’d have a lot to say about this issue, too. But for now I’ll leave it at this: It is wrong to ask people to feel like victims, because once they do, they feel like victims in every area of their lives.

I made a decision: I wasn’t going to be a victim of anyone or for anyone. Not Roman, not the state of California, not the media. I wasn’t going to be defined by what is said about me or expected from me. I was going to tell my story, my truth, through nobody else’s perspective but my own.

And that is what I have done.

I was born Tami Sue Nye on March 31, 1963, eight months before President Kennedy was assassinated and the ground shifted under all of us a little. I have no memory of my biological father, though he called the house once, after he’d been drinking. I’d always assumed my mother decided to change my name, partially to erase him from her life. Later I learned that’s not what happened at all. It was my adoptive father, Jack Gailey, who wanted it changed. Smart girls weren’t named Tami Sue. Dad wanted a smart girl.

We are from York, Pennsylvania, a factory town where the people, mostly of Pennsylvania Dutch descent, produce flooring, water turbines, and Harley-Davidsons. Astroturf was invented here; it’s where York barbells are manufactured, and where the USA Weightlifting Hall of Fame has its headquarters. People born in York usually die in York.

In a town where Ozzie and Harriet were the standard-bearers for family life, we were the oddballs. Dad, who adopted me at three, was in the state legislature for twelve years and later a prominent criminal defense attorney. He was eleven years older than my mother, who was his third wife. Six feet one, bearded and bow-tied, he wore jeans and a macramé belt and a black cape in winter and was radical in his grooming—by which I mean his hair fell below his collar. A prosperous intellectual, he refused to move to a tonier area. Instead my mother, sister, and I were ensconced in an enormous Munsters -like rowhouse in the center of a working-class neighborhood. He held progressive views about race in a town that was deeply divided, where blacks and whites lived on separate sides of the city and you didn’t dare go a few blocks in the wrong direction unless you wanted a beating. These views made him suspect. He also had left his wife and three children and married an actress—my mother. That made him suspect, too.

But then, who wouldn’t fall in love with my mother? She looked like a Hitchcock blonde, but had the effervescence and charm of a car salesman. Which, in a sense, she was: In addition to the jobs she got as a spokesperson in industrial films (she could sell the hell out of a piece of linoleum), she was the Ourisman Chevrolet Girl for their Maryland dealership, declaring cheekily, “You Get Your Way at Ourisman Chevrolet.” Mom was a local celebrity: She had her own glam poster, which the dealerships sold. (Recently, she got a note from someone with an attached photo—“this was my dorm room”—and the posters on the wall were her and Farrah Fawcett.) Her notoriety for those commercials extended to the Oval Office. Mandell “Mandy” Ourisman, the owner of the huge dealership and probably a big Republican donor, was at a White House event; on the receiving line President Nixon reportedly said, “That little girl who does your commercials does a good job. I’d like to meet her someday.”

Читать дальше