James Watson - AVOID BORING PEOPLE - Lessons from a Life in Science

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «James Watson - AVOID BORING PEOPLE - Lessons from a Life in Science» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Биографии и Мемуары. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Despite a brief stopover in Fiji, I felt and looked haggard when I arrived in Sydney just after New Year's. The short brown beard that I had grown in September while lecturing in Ravello led a Sydney newspaper article to describe me as “haunted and Mephistophelean” and “as introverted as his host the physicist Harry Messel was extroverted.” It went on to characterize me as difficult to entertain, a portrayal reflecting several dinner parties given for me by senior academics, not one graced by the face of a pretty girl. In desperation I suggested an evening of nightclubbing only to find that in prudish Sydney chorus girls still danced fully clothed.

My life improved dramatically when a reporter for the Mirror arranged for me to be led around the Paddington art scene by the young painter and critic Robert Hughes. In the Rudy Komen Gallery, I bought the large blue painting Kings Cross Woman by the former boxer Robert Dickerson and a de Kooning-like green-faced woman by the equally talented Jon Molvig. Then we popped into the Kellman Gallery, where I acquired a life-size wooden man from the Sepie River

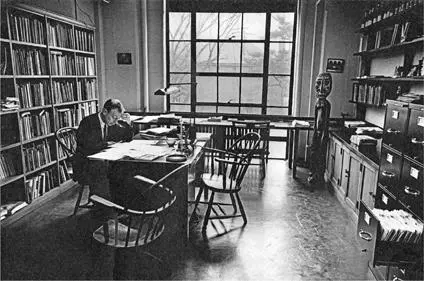

peoples of Papua New Guinea. Its painted Dubuffet-like face later sat across from me at my Biolabs desk. At last in high spirits, I looked forward to a second day of gallery hopping, but Hughes pulled out, making me suspect that women did not make him tick, a notion since copiously disproved.Even before my arrival back at Harvard, I feared my Australian lectures and their written versions were for college, not high school, students and that audiences would get lost. My three completed chapters, I decided, would work better as the start of a little college-level text on how DNA provides the information that enables cellular existence. A chance meeting at the Wursthaus in Harvard Square led me to learn that MIT's molecular biologist, Cyrus Levinthal, was advising the new science textbook company W. A. Benjamin. The firm was eager to expand its initial physics and chemistry list to encompass biochemistry and molecular biology. Less than a week later, its main editor, the young Canadian Neil Patterson, came to my office to make me a Benjamin author, as he had earlier the über-physicist Murray Gell-Mann.

Soon after, I was in W. A. Benjamin's grubby New York City offices, above a bowling alley on Upper Broadway. My discomfort abated when I was told they would soon move to 2 Park Avenue, below Grand Central Station. Liking the way in which Neil Patterson sought out books by clever young scientists, I signed a contract that gave me a $1,000 advance for a 125-page book to be completed late in the year. In addition, I was offered options to buy five thousand shares of Benjamin stock; there seemed reason to hope the stock price would rise as new books rolled out. By then I had given my prospective book the title The Molecular Biology of the Gene (MBG). I was first tempted to call it This Is Life, a titular rejoinder to Erwin Schrödinger's What Is Life? On reflection, however, that would have been promising more than I could deliver.

In writing my new chapters, I used boldface sentences to summarize the main idea conveyed by paragraphs below it (e.g., “Molecules are restrictively sticky;” “Enzymes cannot be used to order amino acids in proteins;” “Template interactions are based on weak bonds

over short distances”). I hit upon “concept heads” as a teaching device when writing the chapter “A Chemist's Look at the Living Cell” before going off to Australia. They naturally emerged from lists of ideas I prepared in outlining what topics each chapter should include. Almost from the start I saw the need to expand upon my Australian chapters, coming up with snappy concept heads such as “The 25-year loneliness of the protein crystallographer.”

In the right-hand corner of my office, the Sepie River wood carving I bought shortly after winning the Nobel Prize supervises my labors.

Equally important to the final readability of MBG was the artwork done by the young Keith Roberts, about to begin his university studies. Early in 1964, Keith had come from England to work as a temporary lab technician prior to reading botany at Cambridge. When I happened to ask his opinion of my first draft chapters, he revealed that he had almost chosen to study art over science, and volunteered to do the necessary illustrations. As my manuscript steadily grew in length, Keith's preoccupation with drawing became full-time, and he continued to draw for me after commencing his freshman year.

At that time, Benjamin was using two-color printing and professional artists. Here I was lucky to have the New York painter Bill Prokus help me transfer Keith's artistic ideas into fixed artwork. Bill then had a studio on Twenty-third Street in Chelsea, where in addition to his own work he did commercial artwork for Benjamin. To speed Bill along, I began coming down regularly to New York City and staying at the Plaza, where the inside rooms never cost more than $20. Even so, Bob Worth, the steel heir who was Benjamin's financial officer, called on me to stop such visits, having read an unfavorable opinion of my then almost finished manuscript. Neil Patterson had sent it to the cell biologist Bob Allen at Dartmouth, who found it unsuitable for his students. Fortunately, Neil prevailed over Bob, and I did not have to stay at the dingy Chelsea Hotel, sited across from Bill Prokus's studio.All my chapter drafts were greatly improved in editing done by the Radcliffe senior Dolly Garter. She had taken George Wald's first-year general-education biology course and so was exposed to the DNA way of thinking. That she was an English major interested in writing was a big plus, and she was able to change many a turgid phrase into freer-flowing language. My challenge became getting the chapters to the point that Dolly could understand them without recourse to Keith's illustrations, often not yet done. If Dolly could follow the words alone, I figured less bright students would not have difficulty with my arguments suitably illustrated. Dolly worked right through the fall of 1964 revising chapters as I wrote them. By then I had expanded MBG's scope, adding the chapters “The Importance of Weak Chemical Interactions” and “Coupled Reactions and Group Transfers” for students coming from biology with weaker backgrounds in chemistry. Together with many later chapters, they needed constant rewriting to keep pace with the latest scientific advances. The countless revisions of the initial galley proofs led to most of MBG being completely reset. Even in page proofs I made many more changes than my publishers wanted, and they threatened to dock me with the charges involved. In the end, they never did so, realizing the value on balance of an up-to-the-minute book.

A wisp of pale, fragile flesh, the Brooklyn-born Dolly belonged to the circle of Harvard's literary magazine The Advocate. So I had her read the first chapters of my memoir about finding the double helix. The book's original title was Honest Jim, since Alfred Tissières earlier had reminded me that Maurice Wilkins's collaborator, Willy Seeds, had cynically addressed me as “Honest Jim” when in August 1955 he met Alfred and me by chance on a path in the Alps. Now, Honest Jim was my way to face head-on the controversial question prompting Seeds's cynicism, over whether Francis and I had improperly used confidential King's College data in working out the structure of DNA. I had in mind the way Joseph Conrad used Lord Jim to pose the basic question as to its hero's character.Dolly's enthusiasm for Honest Jim's first chapters encouraged me to get back to writing once the essential features of MBG were in place. By the time she and her boyfriend, a math major and fellow Brooklynite called Danny, graduated in June, Dolly had read half of Honest Jim. From her new publishing job with Van Nostrand in Princeton, she later wrote telling me that the Harvard Advocate would like to publish its opening chapters. Though the life of a scientist, in her opinion, was of necessity dull, the Advocate's readership would benefit from reading about my exhilarating experiences.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.