James Watson - AVOID BORING PEOPLE - Lessons from a Life in Science

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «James Watson - AVOID BORING PEOPLE - Lessons from a Life in Science» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Биографии и Мемуары. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

I always liked going to grammar school and twice skipped a half grade, graduating when I was just thirteen. Somewhat downcasting were the results of my two IQ tests, discovered by stealthy looks at teachers’ desktops. In neither test did I rise much above 120.1 got more encouragement from my reading comprehension scores, which placed me at the top of my class. I graduated from grammar school in June 1941, just after Germany invaded Russia. By then Churchill had joined Roosevelt as a hero of mine, and on most evenings we listened to Edward R. Murrow reporting from London on the CBS news. That summer was broken by my first time away from my family, going by train for two weeks in August to Owasippe Scout Reservation in Michigan above Muskegon on the White River. There I enjoyed working for nature-oriented merit badges that made me a Life Scout. Less fun were the overnight camping trips, in which I would invariably lag

behind the other hikers, catching up only when they stopped to rest. Nonetheless, I came home content to have spotted thirty-seven different bird species.

Russell Hart (center) and I on the way to Boy Scout camp in 1941

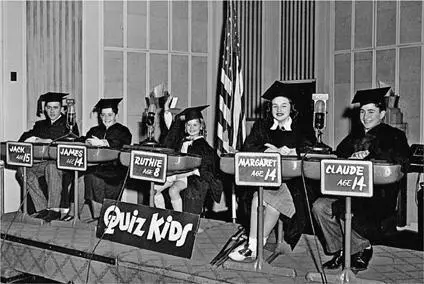

I could not help realizing, however, that as a boy expert on birds I was far behind the much younger Gerard Darrow, who thanks to a prodigious memory became a Chicago celebrity when as a four-year-old ornithologist his story and talent were written up in the Chicago Daily News. I would resent him even more when he became the first famous “Quiz Kid” of a Sunday afternoon radio program that first aired in June 1940. Groups of five children, each of whom received a $100 defense bond, were asked questions by the host, the third-grade-educated Jolly Joe Kelley Previously he had been emcee of the National Barn Dance, having first come to radio fame by reading the funnies on WLS. Almost instantaneously, Quiz Kids became a national sensation, with its weekly listenership between ten million and twenty million—almost half the giant audiences that listened to Jack Benny, Bob Hope, and Red Skelton.

Virtually every Sunday afternoon for over two years, I listened to Quiz Kids hoping that somehow I might get on the program and win a

war bond. Stoking this hope was the fact that one of the show's producers, Ed Simmons, lived in the apartment house next to our bungalow. Finally, because of a successful audition or because of Ed Simmons's influence, I became a fourteen-year-old Quiz Kid in the fall of 1942. My first two appearances went well, with lots of questions suited to my expertise. But my third time on, I was up against an eight-year-old called Ruth Duskin and a battery of questions on the Bible and Shakespeare dominating the thirty-minute horror. I had never been encouraged to know the plots of Shakespeare, and my early Catholic upbringing had furthermore shielded me from any knowledge of the Old Testament. So it was virtually preordained that I would not be one of the three contestants to come back for the next program. When we went home I bitterly felt the want of encyclopedic knowledge and quick wits needed for semipermanence as a Quiz Kid. But I was nevertheless three defense bonds richer. Later these were used to purchase a pair of 7×50 Bausch and Lomb binoculars to replace the ancient pair my father had used as a birder in his youth.

As a Quiz Kid in 1942, second from the left, doomed by my lack of familiarity with the Bible and Shakespeare

By then I was a sophomore at the newly built South Shore High

School. I continued as a largely S (superior) student, though I encountered much more competition than I had at Horace Mann. There was a great Latin teacher, Miss Kinney, who sent me off to the state Latin exams with the more stellar student Marilyn Weintraub, on whom I had a slight crush that no one ever knew about. I was then acutely conscious of my size, only five feet tall when entering high school, and shorter than my sister, who went through puberty early and reached her final height of five feet three inches while I was still only five foot one.

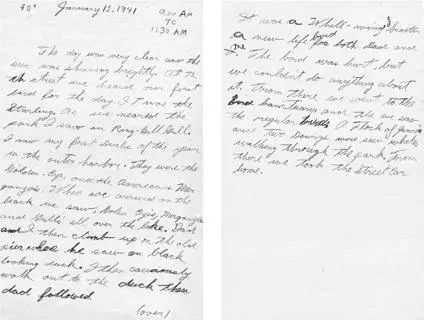

Dad and I spotted the seldom-seen white-winged scoter off Jackson Park in Lake Michigan.

I worked on and off behind a neighborhood drugstore soda fountain making Cokes from syrup and carbonated water. The other conventional teenage job possibility was as a bicycle newspaper delivery boy. But that would have prevented my going on early bird walks with my father and was never seriously considered. Particularly in May, we would routinely get up while it was still dark so we could arrive in Jackson Park soon after sunrise. That way we would have almost two

hours to go after the rarer warblers, principally in the region of Wooded Island. Dad's ear for birdsongs was much better than mine— upon hearing, say, the rough sound of the scarlet tanager, he never mistook it for the more melodious Baltimore oriole, which also migrates into Chicago just after the leaves come out. Afterward, Dad would catch a northbound streetcar to his work, while I would get a trolley going in the opposite direction, which would let me off near school.It was in Jackson Park in 1919 that Dad had met the extraordinarily talented but socially awkward sixteen-year-old University of Chicago student Nathan Leopold, who was equally obsessive about spotting rare birds. In June 1923, Leopold's wealthy father financed a birding expedition so Nathan and my dad could go to the jack pine barrens above Flint, Michigan, in search of the Kirkland warbler. In their pursuit of this rarest of all warblers, they were accompanied by their fellow Chicago ornithologists George Porter Lewis and Sidney Stein, as well as by Nathan's boyhood friend Richard Loeb, whose family helped form the growing Sears, Roebuck store empire.

I had just entered high school when Dad and Mother first told me of Nathan and how for a thrill he and Richard Loeb had brutally killed a younger acquaintance, Bobby Franks. After offering Bobby a ride home from school, they fatally struck him in the head, disposing of the body in a culvert adjacent to the Eggers Wood birding site to which Dad later often brought me. Some six months before Nathan's senseless though nearly perfect crime of May 24,1924, his father contacted mine expressing worry about his son's obsessive fascination with Loeb. Nathan by then was already at the University of Chicago Law School and Dad had no acquaintance with the rich college youths that Leopold and Loeb moved among. In July, Leopold and Loeb were defended in a Chicago courtroom filled with newspapermen by the celebrated Clarence Darrow, who asked Dad to appear as a character witness. But his family advised against this action, saying it would mark him for life in Chicago.

After Darrow had saved his clients’ necks—they were sentenced to life imprisonment without possibility of parole—Nathan wrote Dad proposing a correspondence. But Dad never replied, still horrified by

the crime that had gripped Chicago as none before. Many Leopolds and Loebs changed their names, and my father and Sidney Stein ceased all communication. Many years later, I came across Stein searching, as I was, for May warblers and flycatchers in the dunes near Waukegan above Chicago's North Shore. By then a very successful investment banker, later to be a trustee of the University of Chicago, Stein was acutely embarrassed when I identified myself as Jim Watson's son.There was constant talk at home about the University of Chicago, especially since my father knew its president, Robert Hutchins, whose own father had been a professor of divinity at Oberlin when my father was an undergraduate there. Hutchins had recently enacted an exciting plan for admitting students who had only finished two years of high school and whose brains had not already been rotted out by the banality of high school life. Mother took the lead in seeing that I took the scholarship exam, administered one winter morning in 1943. Soon after, I was invited back to the campus for a personal interview, at which I talked about the books I had lately read, concentrating on Carlo Levi's antifascist statement, Christ Stopped at Eboli. Afterward I was very nervous until the director of admissions, a friend of my mother's, reassured her that I had a decent chance at a full-tuition scholarship. When I got the good news officially, I was too happy to care that my good fortune might have been related to my mother's being well liked by the members of the scholarship committee. Moving on to a world where I might succeed using my head—not based on personal popularity or physical stature—was all that could have mattered to me.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.