James Watson - AVOID BORING PEOPLE - Lessons from a Life in Science

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «James Watson - AVOID BORING PEOPLE - Lessons from a Life in Science» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Биографии и Мемуары. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

5. Focus departmental seminars on new science

The quality of a scientific department is generally revealed by its weekly seminars. Star scientists likely will travel only when they see themselves benefiting from being away from their home base. Seminars that fail to attract broad student audiences will likely bore the largely faculty-constituted audiences, there only for reasons of department loyalty. It's best to invite speakers from emerging disciplines not yet established on your campus. Choosing too many speakers from friends of senior faculty risks giving your students no more than what they already have. Younger faculty members, for the most part, should be in charge of arranging and hosting potentially exciting speakers. They have more time and incentive to do this job well, as they anticipate meeting minds that could enrich their future intellectual lives.

6. Join the editorial board of a new journal

Editorial boards of preexisting journals seldom change fast enough to accommodate new scientific disciplines. A new discipline creates a new discourse and requires a new journal. Editors rooted in the past may not know how to assess the importance of new science, or even whom to approach as a referee. Only six years passed between the finding of the double helix and the founding of the Journal of Molecular Biology. At first I was hesitant to join its editorial board and spend the time looking for the wheat among the chaff. But when the protein crystallographer John Kendrew became its chief editor, I knew the JMB would attract high-quality papers. In return for executing the responsibility to see that important new ideas got out as soon as possible, I was also among the first to benefit from knowing about them.

7. Immediately write up big discoveries

We made a bad mistake in not immediately publishing our lab's February 1960 discovery of T2 messenger RNA. At the time Wally and I wanted the story filled out a bit more by the simultaneous demonstration of E. coli messenger RNA. But the latter task proved much trickier than initially expected. Meanwhile, at Cambridge, Sydney Brenner and Francois Jacob came independently to the concept of messenger RNA in late April, with Sydney soon proving its existence through experiments with Matt Meselson at Caltech. Though we published simultaneously, Sydney let it be known that I had delayed their publication, leading others to believe our Harvard experiments were derivative of theirs. In fact, they predated them by four months.

8. Travel makes your science stronger

No matter how prestigious your own institution, at any given moment the real action in your specialty is likely happening elsewhere. Living in Boston does not mean that you need not continuously monitor the action in other scientific hot spots such as Stanford, Caltech, or La Jolla. Turning down invitations to speak before their audiences works against your future. By moving out of your own turf, you are likely to spot clever graduate students and postdocs who might enhance your own environment. Learning first about clever brains through their publications likely means that someone else has already recruited them. Naturally, there is a point beyond which traveling becomes counterproductive. Whenever possible, you should not cancel lectures for key undergraduate courses. But when you don't have any to give, much time should be spent seeing high-level science done elsewhere.

9. MANNERS NOTICED AS A DISPENSABLE WHITE HOUSE ADVISER

IWAS to wait eight months before the Kennedy administration let me know, in September 1961, that my talents might be of use to them. After we had lunched at the long head table of the Faculty Club, Harvard's physical chemist, George Kistiakowsky, motioned me aside to ask whether I would like to assist the President's Science Advisory Committee (PSAC) in evaluating our nation's biological warfare (BW) capabilities. Curious ever since the end of World War II as to what BW weapons we might have developed, I indicated my availability whenever PSAC wanted me. Now some three years old, PSAC had been created by President Eisenhower as a response to the shock of Sputnik's moving the Soviets into space ahead of us. After James Killian, then president of MIT, George had served as its second leader, reflecting Ike's respect for his acumen at applying science to military purposes. At Los Alamos, his long experience with explosives was used in the fabrication of the first nuclear weapons.

PSAC was now headed by Jerome Wiesner of MIT's big Electronics Lab, who at the war's end was also at Los Alamos. Most of its members were physicists and chemists, reflecting a major preoccupation with nuclear weapons and missiles. George was still a member, as was Paul Doty, who was hopeful that with JFK as president we might be able to slow down, if not stop, the testing of ever bigger hydrogen bombs. Soon I filled out several White House forms for an FBI background check necessary to get me a top-secret security clearance. Only at that level of authorization could I get into Fort Detrick, the nation's big,

rambling biological warfare complex, twenty-five miles to the north of the D.C. line in the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains.

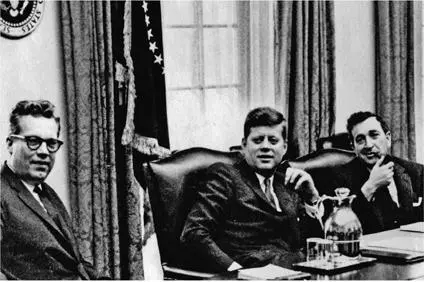

Paul Doty (left) with Jerry Weisner (right) and the president who gave them hope

That fall Wally Gilbert was increasingly in the Biolabs, coming over from the Physics Department, where he still had serious teaching responsibilities. The messenger RNA concept was on everyone's mind, with the previous June's Cold Spring Harbor symposium dominated by its implications. Seeing newly made mRNA molecules functioning in the E. coli cell-free systems made Alfred Tissières wonder whether RNA molecules containing only single bases might also stimulate protein synthesis. But to his disappointment, the polyadenylic acid, or poly A (AAA…), from Paul Doty's lab had no apparent template capabilities. Alfred then put synthetic RNA out of his mind until he came along with Wally and me to hear Marshall Nierenberg's electrifying announcement at the Biological Congress in Moscow in August that polyuridylic acid, or poly U (UUU …), coded for polyphenylalanine. Later poly A was also revealed to have template capabilities coding for polylysine. Its mRNA-like activity had been missed by Alfred, who had the misfortune of being given aggregated poly A incapable of binding to ribosomes.

Upon his return from Moscow, Wally moved into Alfred's former office lab to study interactions between poly U and ribosomes. Over the coming year, Alfred was to spend periods in Paris and Cambridge waiting for his new lab to be completed in Geneva. Several nights before the Tissières were to depart, they joined me and Franny Beer, again my summer technician, for an elegant private supper at the American Academy's new embassy-like home, Brandegee, southwest of Boston. Franny and I drove out in my MG, which I planned to let her borrow while I was away for the coming six weeks. After Moscow, I was to go on to Cambodia, where my sister's husband, Bob Myers, was our CIA station chief, and then to Japan, where Masayasu Nomura would give me an insider's tour of the country.That summer Franny was my daily sounding board about my new Radcliffe friends, the striking blond twins Sophia and Thalassa Hencken. Living in a large, comfortable house in posh Chestnut Hill, they existed in the perpetual shadow of their mother, a garden expert with her own TV show. Though seemingly destined to marry a Social Register type, Thalassa had just discovered a handsome young Pakistani engineer who possessed more panache than was usually dealt out to the suitors of future members of Boston's Vincent Club. Sophia, the less flamboyant of the two, had a boyfriend from New Orleans who, though not appropriate for the Brookline Country Club, did a skillful rendition of Gilbert and Sullivan.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.