James Watson - AVOID BORING PEOPLE - Lessons from a Life in Science

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «James Watson - AVOID BORING PEOPLE - Lessons from a Life in Science» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Биографии и Мемуары. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Then the laboratory was effectively divided into two parts: a year-round Department of Genetics, supported by the Carnegie Institution of Washington, and the Biological Laboratory, a largely summertime effort under the patronage of the wealthy local estate owners. The latter body organized the summer courses and prestigious June meeting, the Cold Spring Harbor Symposium on Quantitative Biology, as well as providing housing and lab benches for summer visitors such as Luria and Delbrück. In 1941, the Yugoslav-born and Cornell-trained Milislav Demerec, the new director of the Department of Genetics, also took control of the community-supported Biological Laboratory, changing its emphasis from physiology and natural history to the study of the gene, his own interest. During his first year as director, Demerec staged the 1941 Cold Spring Harbor Symposium on Genes and Chromosomes. To this seminal meeting came both Hermann J. Müller and Sewall Wright, as well as Max Delbrück and Salvador Luria, for whom Demerec provided space to work together on phages in the Jones Laboratory.

After America entered World War II later that year, Demerec deployed most Biological Lab space to war-related activities. Jones Laboratory, however, being unheated, remained unoccupied and was thus still available to Delbrück and Luria by the time summer came. There were effectively no other wartime summer visitors except for the German-born ornithologist Ernst Mayr, then based at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City, whose research on evolution was complementary to Demerec's interest in genetics. With the director's natural affinity for European-born scientists, Cold Spring Harbor's atmosphere rapidly changed from that of a Yankee bastion, with a history of research in eugenics and an unmistakable anti-Semitic bias, to an international institution whose vigor much depended on foreign visitors, the matter of whose being in some cases Jewish posed no impediment to either scientific involvement or social acceptance.

Cold Spring Harbor was a place where reasoning through numbers was paramount long before Demerec's rule. In 1930 the biophysicist Hugo Fricke was appointed to the Biological Laboratory's staff, and 1933 saw the first Cold Spring Harbor Symposium on Quantitative Biology, its main purpose being to bring physicists and chemists together with biologists to help decipher the molecular basis of life phenomena. It was in this sense quite natural that physicists such as Delbrück and later Szilard were so warmly welcomed into the Cold Spring Harbor community.

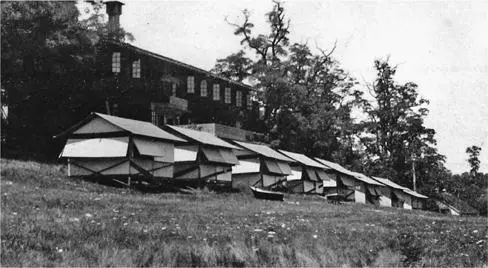

My first afternoon's inspection of the digs and labs for the summer visitors revealed much physical dilapidation, the general atmosphere being that of a run-down summer camp. In fact, some visitors lived in tented cabins sited on the grass behind Blackford Hall, itself centrally heated only many years later. Both Hooper House and Williams

House, then used to house summer scientists with families, were built in the 1830s as “tenements” for workers in the antebellum whaling industry. Equally rundown was the three-story Firehouse, whose name dated from its original use as the town's first fire station before the Biological Lab bought it in 1930 for $50 and transported it across the harbor on a barge to provide more summer housing.

Canvas tents behind Blackford Hall sheltered some summering scientists.

The Laboratory towed in the Cold Spring Harbor Firehouse to house summer scientists in 1930.

The research buildings housing the Department of Genetics dated from the first decade of its existence and, while of far sturdier construction, had an unmistakable turn-of-the-century smell. The main laboratory, an Italianate 1904 building, had a library on the first floor with labs on the top floor and in the basement. On two sides it was surrounded by the cornfields of the Brooklyn-raised and Cornell-trained geneticist Barbara McClintock, whom Demerec had recruited in 1941. Before coming to the symposium that June, she had resigned from the University of Missouri, where her sharp, independent mind was not so well appreciated. Demerec, however, with his eye for real talent, soon got Carnegie's permission to offer her a modest salary and second-floor space in the 1912 Animal House. There mice strains predisposed to cancer had been under intensive study since the early 1920s.

Despite the extraordinarily beautiful surrounding harbor and hills, the state of the labs and residences gave first-time visitors the distinct impression that Cold Spring Harbor would not likely long remain a site of high-powered science. But I then had no concern for the state of the buildings as long as they had the facilities needed for my phage experiments. Our IU contingent was to work in the 1927 Colonial Revival-style Nichols Building, which housed the Biological Laboratory's only two scientists, Vernon Bryson and Albert Keiner. Both did experiments on mutagenic agents in bacteria, and we could use their steam sterilizer (autoclave) and oven to prevent unwanted contamination of our bacterial cultures.

Several days later, Luria arrived with his New York-born wife, Zella, a Ph.D. student in psychology whom he'd met soon after arriving at IU. She was expecting their child at the end of the summer and welcomed the prospect of Blackford meals over preparing food in their Williams House apartment, furnished with castoffs from local estate

owners. Renato Dulbecco by then also was on hand, having driven east in a secondhand Pontiac that he subsequently would use to take his wife and two young children back to Bloomington after their arrival from Italy. One of its first uses on the East Coast was to drive Max Del-briick and his wife, Manny, to the Marine Terminal at La Guardia Airport, where they boarded a Pan Am flying boat to England. From there they were to go on to Germany, where Max's family had suffered badly in the war, his brother, Justus, dying of diphtheria in a Russian prison camp after earlier being incarcerated by the Nazis.

Tracy M. Sonneborn and Barbara McClintock at Cold Spring Harbor in 1946

Back for their sixth straight summer were Ernst Mayr, his wife, Gretel, and their two almost teenage daughters. He had long been one of my heroes, not only for his ornithological expeditions in the late 1920s to New Guinea and the Solomon Islands, but even more because of his seminal 1942 book, Systematics and the Origin of Species. I had excitedly read it during my last year at the University of Chicago, along with the equally influential Genetics and the Origin of Species by Theo-dosius Dobzhansky, a professor at Columbia University and frequent visitor to Cold Spring Harbor to see his close friend Demerec.

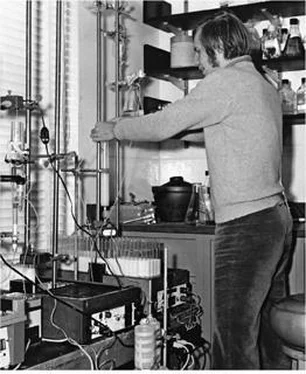

In our Nichols Lab room, Dulbecco and I soon began daily experiments to see whether UV light and X-rays inactivate phages by causing localized damage to one or more of their genes. Luria had arrived hoping that the phenomenon he observed, called multiplicity reactivation (whereby UV-damaged phage particles could somehow still multiply), was best explained by the independent replication of undamaged

genetic determinants. But Renato's experiments soon began to show that the genes surviving a given UV dose replicated more slowly than their unirradiated counterparts. Conceivably there were no independently multiplying sets of phage genes. Instead they might linearly arrange on one or several chromosomes. If so, multiplicity reactivation was the result of crossing-over events between phage chromosomes, with genetic determinants from different particles coming together as a complete set of undamaged phage genes.The summer session mood suddenly transformed when the three-week phage course started on June 28. Attendance in the dining hall almost doubled. It was the fourth year the course was given, and the first time without Delbrück. In his place the main instructor became Mark Adams from New York University's School of Medicine, who had taken the course two years earlier and been converted to full-time phage research. The fourteen students included the medically trained Bernard Davis, working on tuberculosis at Cornell Medical School; Seymour Benzer, a physicist from Purdue University; and Günther Stent, a newly minted polymer chemistry Ph.D. from the University of Illinois, who was to start phage research with Delbrück in the fall at Caltech. I already knew much of what was presented, with the exception of the very new results of August (Gus) Doermann. Prior to coming to Cold Spring Harbor as a junior staff member, Doermann had learned to work with phages as a postdoc under Max at Vanderbilt. Gus described new experiments that for the first time could reveal the number of progeny phages present in infected bacteria as a function of the time following infection. Most exciting, he found that after attachments to their host bacteria, infecting phage particles become transformed into noninfectious replicating bodies. But there was no way then to know what these “replicating forms” were at the chemical level.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.