James Watson - AVOID BORING PEOPLE - Lessons from a Life in Science

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «James Watson - AVOID BORING PEOPLE - Lessons from a Life in Science» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Биографии и Мемуары. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

During its more than thirty-year slumber since 1910, President William L. Bryan had not presided over the construction of even one major new dormitory. So Wells moved quickly to shake things up, recruiting new faculty and using Depression-fighting federal funds to build important new facilities, including a grand four-thousand-seat student auditorium. For science faculty recruiting, Wells tapped Fernandus Payne, who until then had been badly underutilized by the graduate school. A Hoosier born and bred, Payne, like almost all the senior faculty, had gone east to earn his Ph.D., which was awarded in 1909 by Columbia University, where Drosophila, the tiny fruit fly, had just been introduced into the laboratory of T. H. Morgan. Payne had the bad luck to return to Indiana just before Morgan and his students Alfred Sturtevant and Calvin Bridges began their seminal

experiments, mapping genes to fixed locations along the Drosophila chromosomes.Though never a major player in genetics, Payne knew where the action was. He made offers to major talents not yet adequately discovered or recognized by major institutions. From Goucher, the women's college in Baltimore, he recruited the respected cytologist Ralph Cle-land in 1938 for the Botany Department. A year later he brought to the Zoology Department the extraordinary protozoologist Tracy Sonneborn from Johns Hopkins. Then late in 1943, the bacteriology department acquired the Italian-born Salvador Luria, initially trained as an M.D. but by then exploring the genetics of viruses. Even more spectacular was Payne's ability in 1946 to persuade the already world-famous Drosophila geneticist Hermann J. Muller to join ITJ's ranks.

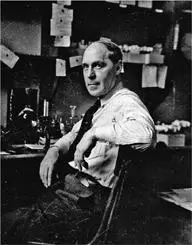

In appointing Sonneborn and Luria, Payne took no notice of the Jewish heritage that had kept Sonneborn from a tenured appointment at Johns Hopkins and Luria from an invitation to join the faculty at the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Columbia University, where he had been given a temporary position upon his arrival as a wartime refugee. Müller, then working with Sewall Wright, the most accomplished of American geneticists, suffered from a double whammy. Not only was he Jewish, but his departure from Texas to Moscow in the early 1930s had indelibly marked him as an unemployable leftist. Upon his return to the States in 1940, only by the intervention of his friend H. H. Plough could he secure a temporary position at Amherst. He had asked many other friends for help, but no major research university made him an offer, even though Müller had by then turned totally against the Soviet government. So it was with great relief that Müller accepted the IU professorship. Soon Indiana would have even greater reason to be pleased when Muller was given the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.

To get to Bloomington I took the Monon, the railroad most identified with Indiana's past and one whose original tracks went past the Gleason farm near La Porte where my grandmother was raised. Along these tracks Nana saw Lincoln's funeral train as it slowly crisscrossed the Midwest toward Springfield, Illinois, where the president was buried. I had signed up to live and eat at the Rogers Center, a

postwar utilitarian dormitory complex located a mile east of the campus center. Its two-story buildings were of necessity built too quickly to have the permanent elegance that comes with Indiana limestone. My $900 fellowship would more than cover room and board fees, leaving me enough for the occasional movie and meal out.

Herman J. Muller, 1941

Some twenty thousand students were then enrolled at IU. All Indiana high school graduates were entitled to enroll there or at rival Purdue, the engineering and agriculture-oriented university a hundred miles north. The state saw its obligation to offer everyone who wanted one a good education. But each year half the freshman class did not go on to be sophomores. Poor grades were behind most dropouts, but a significant number of girls transferred to other schools because of their failure to be accepted by a suitable sorority.

The aged zoology and botany laboratories that dated from the 1880s were in no way adequate for IU's new genetics thrust. Ralph Cleland, upon his 1938 move to the Botany Department, however, had to make do. Tracy Sonneborn had the better fortune a year later of being given space in the relatively new chemistry building. Salvador Luria, coming in 1943, found his new Microbiology Department lab sited in the attic of the early-twentieth-century Kirkwood Hall, originally designed for physics and chemistry, though by then foreign languages and nutrition were taught on lower floors. Hermann J. Muller's lab was hastily created in 1946 in the basement of the equally out-of-date psychology building. As a first-year graduate student, I was given a desk on the top floor of the zoology building, whose original elevator was still operated by pulling ropes to go up and down.

On the first floor of the zoology building were the offices of Alfred Kinsey, much esteemed for his studies on gall wasps, and until recently

the teacher of the undergraduate course on evolution. By 1947, however, his focus had turned exclusively to human sexuality, then a daring topic for any university, particularly one almost in the South. Fortunately, Kinsey's recently published book summarizing his findings was so heavily statistical as to be more likely purgative than prurient. In fact, subsequent criticism that Kinsey seemed ignorant of the emotional aspects of sex later led his Institute of Human Sexuality to accumulate a highly restricted library of erotica. This backfired when some books later purchased in France were seized by U.S. Customs and, despite much pleading by Herman Wells, never released for their scholarly aims.The day after my arrival, I arranged my courses for the coming term. Naturally I signed up for Muller's Advanced Genetics—Mutations and the Gene. I was also urged by Fernandus Payne to take as soon as possible Microbial Genetics with Tracy Sonneborn, since he was zoology's brightest young star. But that term he was only teaching an elementary genetics class, and so I registered for Salvador Luria's course on viruses. Soon I heard faculty gossip that Luria treated his students like dogs. This worried me until I listened to his first several lectures and found them mesmerizing. Less comprehensible to my Zoology Department advisers was my desire to register for Advanced Calculus, a course usually taken only by physics and math majors. But unless I took it, I feared, I would never have the courage to learn more physics, without which I might be precluded from pursuing possible high-powered ways to probe the gene. Ironically, my teacher was to be Lawrence Graves, on sabbatical from the University of Chicago, where I never would have dared enter into one of his courses. But at the more low-key Indiana I would not be competing with real math whizzes— and besides, grades were rather beside the point.

The required text of Muller's course was the lucid and still highly relevant Introduction to Modern Genetics (1939) by the English biologist C. H. Waddington. The heart of the course, however, was Muller's lecture account of his career starting from his days as a student in the “fly room” of Columbia University between 1910 and 1915. Emanating from a short, heavyset man almost the shape of a Drosophila himself, Muller's lectures were streams of consciousness rather than prepared

orations. His agitated speech mingled clever genetic reasoning with details of his frustrations over, say, not initially being accepted into T. H. Morgan's lab, and later when finally a member having his ideas given short shrift. Much less absorbing were the lab sessions, in which we were chaotically run through an increasingly complex set of genetic crosses. The insights of such experiments seemed rather arcane, pointing to a truth that could not be avoided: Drosophila's days as a model organism were over. Indeed, a new one would soon supplant it as the premier tool for studying the gene.Through Luria's virus course lectures, I saw the genetic wave of the future unfolding. The key would be microorganisms, whose short life cycles would permit genetic crosses to be done and analyzed in a matter of days instead of weeks or months. Luria was particularly excited about the future of research using the common intestinal bacterium Escherichia colt and its parasitic viruses, the bacteriophages (or phages for short, as they were more often called). Soon after his 1943 arrival in Bloomington Luria, then thirty-one, was the first to systematically show that both E. coli and its phages gave rise to easily identifiable spontaneous mutants. Only three years later, in 1946, was genetic recombination between different E. coli strains demonstrated by the precocious twenty-one-year-old Joshua Lederberg, then a medical student in Edward Tatum's laboratory at Yale. The same year Alfred Hershey at Washington University found genetic recombination for the E. colt phages T2 and T4 and soon constructed the first genetic maps of phage chromosomes.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.