Lev Rosenblum, “Kamenev,” well-off Tiflis engineer’s son, moderate Bolshevik

Mikhail “Misha” Kalinin, peasant, butler, early Bolshevik in Tiflis

Suren Spandarian, son of well-off Armenian editor, Bolshevik, womanizer, Stalin’s best friend

Stepan Shaumian, well-off Armenian Bolshevik, Stalin’s ally and rival

Grigory “Sergo” Ordzhonikidze, poor nobleman, nurse, Bolshevik hard man, Stalin’s longtime ally

Sergo Kavtaradze, young henchman of Stalin in western Georgia, Baku, St. Petersburg

WIVES AND IN-LAWS

Alexander “Alyosha” Svanidze, seminarist, Stalin friend, early Bolshevik and later brother-in-law

Alexandra “Sashiko” Svanidze, sister of above and Stalin friend

Mikheil Monoselidze, Sashiko’s husband and Bolshevik ally of Stalin

Maria “Mariko” Svanidze, sister of Sashiko and Alyosha

Ekaterina “Kato” Svanidze Djugashvili, youngest of family, Stalin’s first wife and mother of

Yakov “Yasha” or “Laddie” Djugashvili, Stalin’s son

Sergei Alliluyev, railway and electrical manager, early Bolshevik, Stalin ally in Tiflis, Baku and St. Petersburg

Olga Alliluyeva, wife of Sergei, early Stalin friend, possibly mistress, later mother-in-law

Pavel Alliluyev, son of Olga

Anna Alliluyeva, daughter of Olga

Fyodor “Fedya” Alliluyev, son of Olga

Nadezhda “Nadya” Alliluyeva, daughter of Sergei and Olga, Stalin’s second wife

GANGSTERS, MASTERMINDS AND FIXERS

Kamo, Simon “Senko”Ter-Petrossian, Stalin’s friend, protégé, then bank robber and hitman

Kote Tsintsadze, Stalin’s hitman and brigand in western Georgia and later bank-robbery chief

Leonid Krasin, Lenin’s master of bomb-making, money-laundering, bank robberies and elite contacts, later fell out with Lenin

Meyer Wallach, “Maxim Litvinov,” Bolshevik arms-dealer and money-launderer

Andrei Vyshinsky, well-off Odessa pharmacist’s son, brought up in Baku, Stalin’s enforcer and later Menshevik

THE TITAN OF MARXISM

Georgi Plekhanov, father of Russian Social-Democracy

THE BOLSHEVIKS

Vladimir Illich Ulyanov, “Lenin,” or “Illich” to his intimates, Russian SD leader and founder of Bolsheviks

Nadezhda Krupskaya, his wife and assistant

Grigory Radomyslsky, “Zinoviev,” Jewish milkman’s son, Lenin’s sidekick in Cracow, then ally of Kamenev

Roman Malinovsky, burglar, rapist and Okhrana spy, Bolshevik leader in the Imperial Duma

Yakov Sverdlov, Jewish Bolshevik leader and Stalin’s roommate in exile

Lev Bronstein, “Trotsky,” leader, orator and writer, independent Marxist, Menshevik Chairman of the Petersburg Soviet in 1905, joined Bolsheviks in 1917

Felix Dzerzhinsky, Polish nobleman, veteran revolutionary, joined Bolsheviks in 1917

Elena Stasova, “Absolute” and “Zelma,” noblewoman and Bolshevik activist

Klimenti Voroshilov, Lugansk lathe-turner, Bolshevik friend of Stalin, roommate in Stockholm

Vyacheslav Scriabin, “Molotov,” young Bolshevik and founder with Stalin of Pravda

THE MENSHEVIKS

Yuli Tsederbaum, “Martov,” Lenin’s friend then bitter enemy, founder of Mensheviks

Noe Jordania, founder of Georgian Social-Democracy and leader of Georgian Mensheviks

Nikolai “Karlo” Chkheidze, moderate Menshevik in Batumi and later in St. Petersburg

Isidore Ramishvili, Menshevik enemy of Stalin

Said Devdariani, Seminary friend then political enemy and Menshevik

Noe Ramishvili, tough Menshevik enemy of Stalin

Minadora Ordzhonikidze Toroshelidze, Menshevik friend of Stalin and wife of Bolshevik ally Malakia Toroshelidze

David Sagirashvili, Georgian Menshevik and memoirist

Grigol Uratadze, Georgian Menshevik and memoirist

Razhden Arsenidze, Georgian Menshevik and memoirist

Khariton Chavichvili, Menshevik memoirist

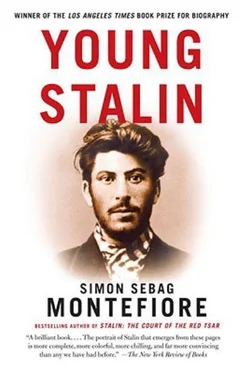

STALIN

Stalin did not start to use his renowned name until 1912: it only became his surname after October 1917. His real name was Josef Vissarionovich Djugashvili. His mother, friends and comrades called him “Soso” even after 1917. He published poems as “Soselo.” He increasingly called himself “Koba,” but he used many names in the course of his secret life.

For the sake of clarity, “Stalin” and “Soso” are used throughout the book.

NAMES AND TRANSLITERATIONS

I have followed the same principles as I did in my other books on Russia. Wherever possible, I have tried to use the most recognizable, best-known and most easily transliterated versions of the Georgian and Russian names. Of course, this leads to many inconsistencies—for example, I call the Georgian Menshevik leader Noe Jordania, not Zhordania, and use Jibladze, not Djibladze, yet I feel I must spell Stalin’s real name Djugashvili because it is so well known by that spelling. I use the French spellings of Davrichewy and Chavichvili (instead of Davrishashvili and Shavishvili) because their memoirs are published under these names. I apologize to the many linguists who may be appalled by this.

DATES

Dates are given in the Old Style Julian Calendar, used in Russia, which ran thirteen days behind the New Style Gregorian Calendar used in the West. When describing events in the West, both dates are given. The Soviet government switched to the New Style Calendar at midnight on 31 January 1918 with the next day declared 14 February.

MONEY

In early-twentieth-century rates, 10 roubles = £1. The simplest way to convert this into today’s money is to multiply by five to get pounds sterling and by ten to get U.S. dollars. A couple of examples: as a labourer in the Rothschild refineries in Batumi, young Stalin received 1.70 roubles per day, or 620 per annum ($6,000 or £3,000 per annum today). Tsar Nicholas II paid himself a personal allowance of 250,000 roubles a year while the bodyguard of the Tsarevich Alexei was paid a salary of 120 roubles a year ($1,200 or £600 per annum today). Yet these numbers are meaningless: the figures give little idea of real buying power and value. For example, Nicholas II was probably the richest man in the world, certainly in Russia. Yet his entire personal wealth of land, jewels, palaces, art and mineral deposits were calculated in 1917 as being worth 14 million roubles which, transferred into today’s money, is a mere $140 million or £70 million—clearly an absurdly small figure.

TITLES

There are not always equivalents of Tsarist titles and ranks but I have tried to use as close an equivalent as possible. For the Russian autocrats, I use “Tsar” and “Emperor” interchangeably. Tsar Peter the Great crowned himself “Emperor” in 1721. The title of the ruler of the Caucasus varied. Grand Duke Mikhail Nikolaievich, son and brother of emperors, was the viceroy. His successor, Prince Grigory Golitsyn, in office during Stalin’s seminary days, had the lesser rank of governor-general. His successor Count Illarion Vorontsov-Dashkov would again be viceroy in 1905–16.

DISTANCES/WEIGHTS

10 versts = 6.63 miles

1 pud = 36 lb.

Prologue

The Bank Robbery

At 10:30 a.m. On the sultry morning of Wednesday, 26 June 1907, in the seething central square of Tiflis, a dashing moustachioed cavalry captain in boots and jodhpurs, wielding a big Circassian sabre, performed tricks on horseback, joking with two pretty, well-dressed Georgian girls who twirled gaudy parasols—while fingering Mauser pistols hidden in their dresses.

Raffish young men in bright peasant blouses and wide sailor-style trousers waited on the street corners, cradling secreted revolvers and grenades. At the louche Tilipuchuri Tavern on the square, a crew of heavily armed gangsters took over the cellar bar, gaily inviting passers-by to join them for drinks. All of them were waiting to carry out the first exploit by Josef Djugashvili, aged twenty-nine, later known as Stalin, to win the attention of the world. {2}

Читать дальше