With the first clap of thunder, my dad flinched.

I grinned nervously at him.

Then:

Bong!

Bong!

Bong!

My dad coughed.

Bong!

Bong!

Bong!

He coughed again.

Bong!

Bong!

Bong!

‘Son, when does—’

BLAM! Dow! Dowwwwwww!!! Dooooowwwwww!!!!!

My poor old man turned white. I think he’d been expecting something along the lines of

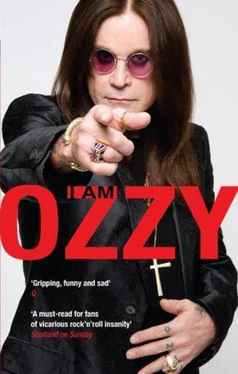

‘Knees up Mother Brown’. But I left the record on anyway. Finally, after six minutes and eighteen seconds of Tony and Geezer thrashing away on their guitars, Bill beating the shit out of his drums, and me howling on about a man in black coming to take me away to the lake of fire, my dad rubbed his eyes, shook his head and looked at the floor.

Silence.

‘What d’you think, Dad?’

‘John,’ he said, ‘are you absolutely sure you’ve only been drinking the occasional beer?’

I went bright red and said something like ‘Oh, er, yeah, Dad, whatever.’

Bless him, he just didn’t get it at all.

But it broke my heart, y’know? I’d always felt as though I’d let my father down. Not because of anything he’d ever said to me. But because I was a failure at school, because I couldn’t read or write properly, because I’d been sent to prison, and because I’d been fired from all of those factory jobs. But now, finally, with Black Sabbath, I was doing something I was good at, that I enjoyed, that I was prepared to work hard at. I suppose I just really wanted my old man to be proud of me. But it wasn’t his fault—it was the way he was. It was his generation.

And I think deep down he was proud of me, in his own way.

I can honestly say that we never took the black magic stuff seriously for one second. We just liked how theatrical it was. Even my old man eventually played along with it: he made me this awesome metal cross during one of his tea breaks at the factory. When I turned up to rehearsals with it, all the other guys wanted one, so I got Dad to make three more.

I couldn’t believe it when I learned that people actually ‘practised the occult’. These freaks with white make-up and black robes would come up to us after our gigs and invite us to black masses at Highgate Cemetery in London. I’d say to them, ‘Look, mate, the only evil spirits I’m interested in are called whisky, vodka and gin.’ At one point we were invited by a group of Satanists to play at Stonehenge. We told them to fuck off, so they said they’d put a curse on us. What a load of bollocks that was. Britain even had a ‘chief witch’ in those days, called Alex Sanders. Never met him. Never wanted to. Mind you, we did buy a Ouija board once and have a little seance. We scared the shit out of each other.

That night, at God knows what hour, Bill phoned me up and shouted, ‘Ozzy, I think my house is haunted!’

‘Sell tickets then,’ I told him, and put the phone down.

The good thing about all the satanic stuff was that it gave us endless free publicity. People couldn’t get enough of it. During its first day of release, Black Sabbath sold five thousand copies, and by the end of the year it was on its way to selling a million worldwide.

None of us could believe it.

Not even Jim Simpson could believe it—the poor bloke ended up getting completely over-whelmed. His office was in Birmingham, miles away from the action in London, and he had other bands to look after, no staff, and Henry’s Blues House to run. So it didn’t take long for us to start getting pissed off with him. For starters, we weren’t getting any dough. Jim wasn’t robbing us—he’s one of the most honest people I’ve ever met in the music business—but Philips were taking forever to cough up our royalties, and Jim wasn’t the kind of bloke who could go down there and bully them into paying. Then there was the issue of America: we wanted to go, immediately. But we had to get it right, which meant going easy on all the satanic stuff, ’cos we didn’t want to come across like fans of the Manson Family.

We’d get strung up by our balls if we did.

It didn’t take long for all the sharks down in London to realise there was blood in the water, as far as Jim was concerned. So, one by one, they started circling. They looked at us and they saw big fucking neon-lit pound signs. Our first album couldn’t have cost more than five hundred quid to make, so the profit margins were astronomical.

The first call we got was from Don Arden. We didn’t know much about him apart from his nickname—‘Mr Big’. Then we heard stories about him dangling people out of his fourth-floor Carnaby Street office window, stubbing cigars out on people’s foreheads, and demanding all his contracts be paid in cash and delivered by hand in brown paper bags. So we were shitting ourselves when we went down to London to meet him for the first time. When we got off the train at Euston Station, he had his blue Rolls-Royce waiting to pick us up. It was the first time I’d ever been in a Roller. I sat there in the back seat, like the King of England, thinking, Three years ago, you were a puke remover in a slaughterhouse, and before that you were doling out slop to child molesters in Winson Green. Now look where you are.

Don had a reputation as the kind of guy who could make you world famous but would rip you off while he was at it. It’s not like he was pulling any complex, high finance, Bernie Madoff-type scams. He just wouldn’t fucking pay. Simple as that. It would be like, ‘Don, you owe me a million quid, can I have the money please?’ And he’d go, ‘No, you can’t.’ End of conversation. And if you ever went to his office to ask for the dough in person, there was a good chance you’d leave in the back of an ambulance.

But the thing with us was, we didn’t really need anyone to make us world famous—we were already halfway there. Still, we sat in Don’s office and listened to his pitch. He was a short bloke, but with the build and presence of a pissed-off Rottweiler, and he had this incredible shouty voice. He’d pick up the phone to his receptionist and scream so loud the whole planet seemed to shake.

When the meeting was over we all stood up and said how great it was to meet him, blah-blah-blah, even though none of us wanted anything more to do with him. Then, as we filed out of his office, he introduced us to the chick he’d spent half the meeting bawling at over the phone.

‘This is Sharon, my daughter,’ he growled. ‘Sharon, take these lads down to the car, will you?’

I grinned at her, but she gave me a wary look. She probably thought I was a lunatic, standing there in my pyjama shirt, with no shoes and a hot-water tap on a piece of string around my neck.

But then, when Don huffed back to his office and closed the door behind him, I cracked a joke and made her smile. I just about fell on the floor. It was the most wicked, beautiful smile I’d ever seen in my life. And she had the laugh to go with it, too. It made me feel so good, hearing her laugh. I just wanted to make her do it again and again and again.

To this day, I feel bad about what happened with Jim Simpson. I think he got the wrong end of the stick with us. I suppose it’s easy to say what he should or shouldn’t have done with hind-sight, but if he’d admitted to himself that we were too big for him to handle, he could have sold us off to another management company, or contracted out our day-to-day management to a bigger firm. But he wasn’t strong enough to do that. And we were so desperate to go to America and get our big break that we didn’t have the patience to wait for him to sort himself out.

In the end it was a wide boy called Patrick Meehan who nabbed us. He was only a couple of years older than us, and he’d gone into the management racket with his father, who’d been a stuntman on the TV show Danger Man and then worked for Don Arden, first as a driver, then as a general lackey, looking after the likes of the Small Faces and the Animals. Patrick had another ex-Don Arden henchman working with him too: Wilf Pine. I liked Wilf a lot. He looked like a cartoon villain: short, built like a slab of concrete, and with this big, tasty, hard-boiled face. I think his hardman routine was all a bit of an act, to be honest with you, but there was never any doubt that he could do some serious damage if he was in the mood. He’d been Don’s personal bodyguard for a long time, and when I knew him he’d often go down to Brixton Prison to see the Kray twins, who’d only just been put away. He was all right, was Wilf. We’d have a laugh. ‘You’re crazy, d’you know that?’ he’d say to me.

Читать дальше