Then we had to go and find the Hirschen Club, which turned out to be even sleazier than the Star Club. They had this tiny little stage with the bar just a few feet away, and it was dark and there were hookers hanging around all over the place. The four of us had to share one crappy room upstairs, so getting a chick with her own place was the order of the day.

One night, these two girls in fishnets invited me and Geezer back to their apartment. They were obviously on the game, but I was up for anything that would spare me from another night of sharing a bed with Bill, who spent the whole time complaining about my smelly feet.

So when they sweetened the deal by saying they had some dope, I said, ‘Fuck it, let’s go.’ But Geezer wasn’t so sure. ‘They’re hookers, Ozzy,’ he kept saying. ‘You’ll catch something nasty. Let’s find some other chicks.’

‘I ain’t gonna bonk either of ’em,’ I said. ‘I just wanna get out of this fucking place.’

‘I’ll believe that when I see it,’ said Geezer. ‘The dark-haired chick isn’t so bad-looking.

After a few beers and a few puffs of the magic weed, she’ll have her way with me.’

‘Look,’ I said, ‘if she makes a move on yer, I’ll kick her up the arse and we’ll leave, all right?’

‘Promise?’

‘If she makes one move towards your knob, Geezer, I’ll pull her off you and we’ll fuck off.’

‘All right.’

So we go back to their place. It’s all dimly lit, and Geezer’s on one side of the room with the dark-haired chick, and I’m on the other side with the ugly one, and we’re smoking weed and listening to the album by Blind Faith, the ‘supergroup’ formed by Eric Clapton, Ginger Baker, Steve Winwood and Ric Grech. For a while it’s all serene and trippy—the music’s playing and everyone’s snogging and fumbling around. Then, all of a sudden, this deep Brummie voice rises out of the mist of dope smoke.

‘Oi, Ozzy,’ says Geezer. ‘Time to put the boot in.’

I looked over and this hooker was straddling him as he lay there with his eyes closed and this pained expression on his face. I honestly thought it was the funniest thing I’d ever seen in my life.

I don’t even know if he shagged her in the end. I just remember laughing and laughing and laughing until I cried.

Jim Simpson wanted to see us at his house as soon as we got back from Switzerland.

‘I’ve got something you need to see,’ he said, in this ominous voice.

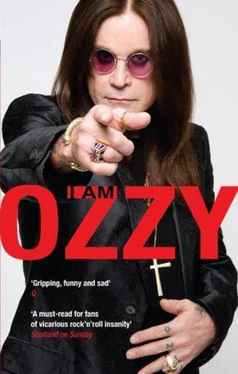

So that afternoon we all met up in his living room and sat there, twiddling our thumbs, wondering what the fuck he was going to say. He reached into his briefcase and pulled out the finished record of Black Sabbath. We were speechless. The cover was a spooky-looking fifteenth-century watermill (I later found out it was the Mapledurham Watermill on the River Thames in Oxfordshire), with all these dead leaves around it and a sickly looking woman with long dark hair, dressed in black robes, standing in the middle of the frame with a scary look on her face. It was amazing. Then, when you opened the gatefold sleeve, there was just black everywhere and an inverted cross with a creepy poem written inside it. We’d had no input with the artwork, so the inverted cross—a symbol of Satanism, we later found out—had nothing to do with us. But the stories that you hear about us being unhappy with it are total bullshit. As far as I can remember, we were immediately blown away by the cover. We just stood there, staring at it, and going, ‘Fucking hell, man, this is fucking unbelievable.’

Then Jim went over to his record player and put it on. I almost burst into tears, it sounded so great. While we’d been in Switzerland, Rodger and Tom had put these sound effects of a thunderstorm and a tolling bell over the opening riff of the title track, so it sounded like something from a film. The overall effect was fabulous. I still get chills whenever I hear it.

On Friday the thirteenth of February 1970, Black Sabbath went on sale.

I felt like I’d just been born.

But the critics fucking hated it.

Still, one of the few good things about being dyslexic is that when I say I don’t read reviews, I mean I don’t read reviews. But that didn’t stop the others from poring over what the press had to say about us. Of all the bad reviews of Black Sabbath, the worst was probably written by Lester Bangs at Rolling Stone. He was the same age as me, but I didn’t know that at the time. In fact, I’d never even heard of him before, and once the others told me what he’d written I wished I still hadn’t. I remember Geezer reading out words like ‘claptrap’, ‘wooden’ and ‘dogged’. The last line was something like, ‘They’re just like Cream, but worse’, which I didn’t understand, because I thought Cream were one of the best bands in the world.

Bangs died twelve years later, when he was only thirty-three, and I’ve heard people say he was a genius when it came to words, but as far as we were concerned he was just another pretentious dickhead. And from then we never got on with Rolling Stone. But y’know what?

Being trashed by Rolling Stone was kind of cool, because they were the Establishment.

Those music magazines were all staffed by college kids who thought they were clever—which, to be fair, they probably were. Meanwhile, we’d been kicked out of school at fifteen and had worked in factories and slaughtered animals for a living, but then we’d made something of ourselves, even though the whole system was against us. So how upset could we be when clever people said we were no good?

The important thing was someone thought we were good, ’cos Black Sabbath went straight to number eight in Britain and number twenty-three in America.

And the Rolling Stone treatment prepared us for what was to come. I don’t think we ever got a good review for anything we did. Which is why I never bother with reviews. Whenever I hear someone getting upset about reviews, I just say to them, ‘Look, it’s their job to criticise. That’s why they’re called critics.’ Mind you, some people just get so wound up they can’t control themselves. I remember one time in Glasgow this critic showed up at our hotel, and Tony goes over to him and says, ‘I wanna have a word with you, sunshine.’ I didn’t know it at the time, but the guy had just written a hit-piece on Tony, describing him as ‘Jason King with builder’s arms’—Jason King being a private-eye type character on TV at the time who had this stupid moustache and dodgy haircut. But when Tony confronted him, he just laughed, which was a really stupid thing to do. Tony just stood there and said, ‘Go on, son, finish laughing, ’cos in about thirty seconds you ain’t gonna be laughing any more.’ Then he started to laugh himself. The critic didn’t take him seriously, so he kept on laughing, and for about two seconds they were both just standing there, laughing their heads off. Then Tony swung his fist back and just about put this bloke in hospital. I never read his review of the show, but I’m told it wasn’t very flattering.

My old man wasn’t too impressed with our first album, either.

I’ll always remember the day I took it home and said, ‘Look, Dad! I got my voice on a record!’

I can picture him now, fiddling with his reading specs and holding the cover in front of his face. Then he opened the sleeve, went ‘Hmm’ and said, ‘Are you sure they didn’t make a mistake, son?’

‘What d’you mean?’

‘This cross is upside down.’

‘It’s supposed to be like that.’

‘Oh. Well, don’t just stand there. Put it on. Let’s have a bit of a sing-along, eh?’

So I walked over to the radiogram, lifted the heavy wooden lid, put the record on the turntable—hoping the dodgy speaker that I’d put in there from the PA would work—and cranked up the volume.

Читать дальше