Slash with Anthony Bozza

SLASH

To my loving family, for all their support through the good times and the bad

And to Guns N’ Roses fans everywhere, old and new; with out their undying loyalty and limitless patience, none of this would matter

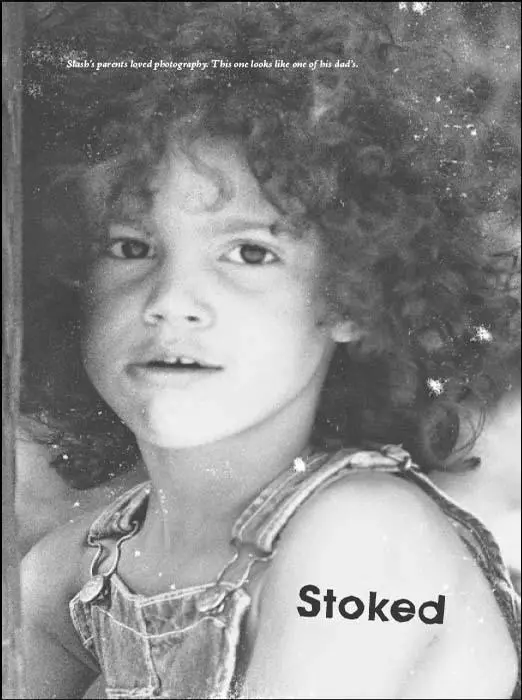

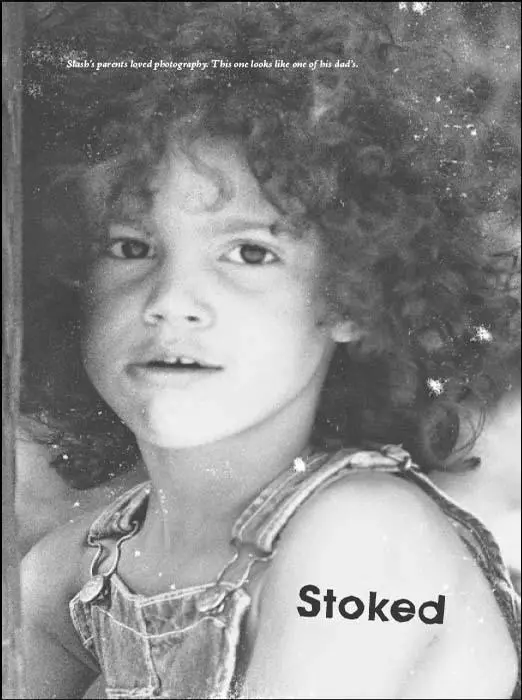

Slash’s parents loved photography. Tis one looks like one of his dad’s.

I was born on July 23, 1965, in Stoke-on-Trent, England, the town where Lemmy Kilmister of Motörhead was born twenty years before me. It was the year rock and roll as we know it became greater than the sum of its parts; the year a few isolated bands changed pop music forever. The Beatles released Rubber Soul that year and the Stones released Rolling Stones No. 2 , the best of their collections of blues covers. There was a creative revolution afoot that has never been equaled and I’m proud to be a by-product of it.

My mom is an African American and my dad is English and white. They met in Paris in the sixties, fell in love, and had me. Their brand of interracial intercontinental communion wasn’t the norm; and neither was their boundless creativity. I thank them for being who they are. They exposed me to environments so rich and colorful and unique that what I experienced even while very young made a permanent impression on me. My parents treated me as an equal as soon as I could stand. And they taught me, on the fly, how to deal with whatever came my way in the only type of life I’ve ever known.

Tony Hudson and his sons, 1972. Slash looks exactly like his son London here.

My mom, Ola, was seventeen and my dad, Anthony (“Tony”), was twenty when they met. He was born a painter, and like painters historically do, he left his stuffy hometown to find himself in Paris. My mom was precocious and exuberant, young and beautiful; she’d left Los Angeles to see the world and make connections in fashion. When their journeys intersected they fell in love, then got married in England. And then I came along and they set about creating their life together.

My mom’s career as a costume designer started around 1966, and over the course of it, her clients included Flip Wilson, Ringo Starr, and John Lennon. She also worked for the Pointer Sisters, Helen Reddy, Linda Ronstadt, and James Taylor. Sylvester was one of her clients, too. He is no longer with us, but he was once a disco artist who was like the gay Sly Stone. He had a great voice and he was a supergood person in my eyes; he gave me a black-and-white rat that I named Mickey. Mickey was a badass. He never flinched when I fed rats to my snakes. He survived a fall from my bedroom window after he was tossed out by my younger brother, and was no worse for the wear when he showed up at our back door three days later. Mickey also survived the accidental removal of a section of his tail when the inner chassis of our sofa bed cut it off, as well as close to a year without food or water. We left him behind by mistake in an apartment that we used as storage space, and when we eventually popped in to pick up some boxes, Mickey came up to me congenially as if I’d been gone only a day, as if to say, “Hey! Where you been?”

Mickey was one of my more memorable pets. There have been many, from my mountain lion, Curtis, to the hundreds of snakes I’ve raised. Basically I am a self-taught zookeeper and I definitely relate to the animals I’ve lived with better than to most of the humans I’ve known. Those animals and I share a point of view that most people forget: at the end of the day life is about survival. Once that lesson is learned, earning the trust of an animal that might eat you in the wild is a defining and rewarding experience.

SOON AFTER I WAS BORN, MY MOTHER returned to L.A. to expand her business and to lay the financial foundation our family was built upon. My dad raised me in England at his parents’, Charles and Sybil Hudson’s, home for four years—and it wasn’t easy on him. I was a pretty intuitive kid, but I could not discern the depth of the tension there. My dad and his dad, Charles, from what I understand, had less than the best relationship. Tony was the middle of three sons, and he was every bit the middle child upstart. His younger brother, Ian, and his older brother, David, were much more in step with the family’s values. My dad went to art school; he was everything his father wasn’t. Tony was the sixties; and he stood up for his beliefs as wholeheartedly as his father condemned them. My grandfather Charles was a fireman from Stoke, a community that had somehow skated through history unchanged. Most residents of Stoke never leave; many, like my grandparents, had never ventured the hundred or so miles south to London. Tony’s unyielding vision of attending art school and making a living through painting was something Charles could not stomach. Their clash of opinion fueled constant arguments and often led to violent exchanges; Tony claims that Charles beat him senseless on a regular basis for most of his youth.

My grandfather was as consummately representative of 1950s Britain as his son was of the sixties. Charles wanted to see everything in its right place while Tony wanted to rearrange and repaint it all. I imagine that my grandfather was properly appalled when his son returned from Paris in love with a carefree black American. I wonder what he said when Tony told him that he intended to be married and raise their newborn child under their roof until he and my mom got their affairs in order. All things considered, I’m touched by how much diplomacy was displayed by the parties involved.

MY DAD TOOK ME TO LONDON AS SOON as I could handle the train ride. I was maybe two or three, but instinctively I knew how far away it was from Stoke’s unending miles of brown brick row houses and quaint families because my dad was into a bit of a bohemian scene. We’d crash on couches and not come back for days. There were Lava lamps and black lights, and the electric excitement of the open booths and artists along Portobello Road. My dad never considered himself a Beat, but he had absorbed that kind of lifestyle through osmosis. It was as if he had handpicked the highlights of that type of life: a love of adventure, hitting the road with nothing but the clothes on your back, finding shelter in apartments full of interesting people. My parents taught me a lot, but I learned their greatest lesson early—nothing else is quite like life on the road.

I remember the good things about England. I was the center of my grandparents’ attention. I went to school. I was in plays: The Twelve Days of Christmas ; I was the lead in The Little Drummer Boy . I drew all the time. And once a week I watched The Avengers and The Thunderbirds . Television in late sixties England was extremely limited and reflected the post–World War II, Churchill view of the world of my grandparents’ generation. There were only three channels back then, and aside from the two hours a week that any of them played those two programs, all three played only the news. It’s no wonder that my parents’ generation threw themselves headfirst into the cultural shift that was afoot.

Once Tony and I joined Ola in Los Angeles, he never spoke to his parents again. They disappeared from my life quickly and I often missed them growing up. My mother encouraged my father to stay in touch but it made no difference; he had no interest. I didn’t see my English relatives again until Guns N’ Roses became well known. When we played Wembley Stadium in 1992, the Hudson clan came out in force: backstage before the show I witnessed one of my uncles, my cousin, and my grandfather, on his very first trip to London from Stoke, down every drop of liquor in our dressing room. Consumed in full, our booze rider in those days would have killed anyone but us.

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу

![Сол Слэш Хадсон - Slash. Демоны рок-н-ролла в моей голове [litres]](/books/387912/sol-slesh-hadson-slash-demony-rok-n-thumb.webp)