After school, I hung out at bike shops and became part of a team riding for a store called Spokes and Stuff, where I began to collect a bunch of much older friends—some of the other older guys worked at Schwinn in Santa Monica. Ten or so of us would ride around Hollywood every night and all of us but two—they were brothers—came from disturbed or broken domestic situations of some kind. We found solace in one another’s company: our time spent together was the only regular companionship any of us could count on.

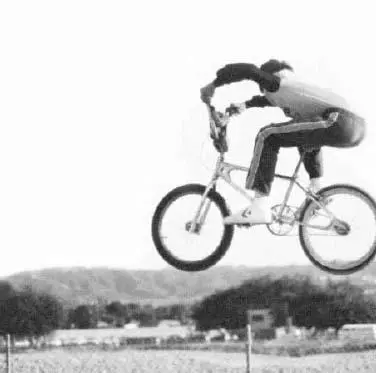

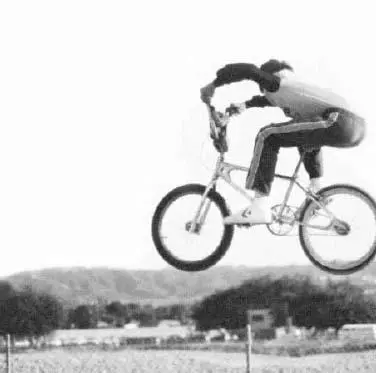

We would meet up every afternoon in Hollywood and ride everywhere from Culver City to the La Brea Tar Pits, treating the streets as our bike park. We’d jump off every sloped surface we could find, and whether it was midnight or the middle of rush hour, we always disrespected the pedestrians’ right of way. We were just scrappy kids on twenty-inch-high bikes, but multiplied by ten, in a pack, whizzing down the sidewalk at top speed, we were a force to be reckoned with. We’d jump onto a bus bench, sometimes while some poor stranger was sitting there, we’d hop fire hydrants, and we’d compete constantly to outdo one another. We were disillusioned teenagers trying to navigate difficult times in our lives, and we did so by bunny-hopping all over the sidewalks of L.A.

We’d ride this dirt track out in the Valley, by the youth center in Reseda. It was about fifteen miles away from Hollywood, which is an ambitious goal on a BMX bike. We used to hitch rides on bumpers over Laurel Canyon Boulevard to cut down on our travel time. It’s nothing I’d advise, but we treated passing cars like seats on a ski chairlift: we’d wait on the shoulder, then one by one we’d grab a car and ride it up the hill. Balancing a bike, even one with a low center of gravity, while holding on to a car driving thirty or forty miles an hour is thrilling but tricky on flat ground; attempting it on a series of tight uphill S curves like Laurel Canyon is something else. I’m still not sure how none of us were ever run over. It surprises me more to remember that I did that ride, both up and down hill, without brakes more often than not. In my mind, being the youngest meant that I had something to prove to my friends every time we rode: judging by the looks on their faces after some of my stunts, I succeeded. They might have been only teenagers but my friends weren’t easily impressed.

To tell you the truth, we were a gnarly little gang. One of them was Danny McCracken. He was sixteen; a strong, heavy, silent type, he was already a guy everyone instinctively knew not to fuck with. One night Danny and I stole a bike with bent forks and while he deliberately bunny-hopped it to break the forks and make us all laugh, he fell over the handle-bars and slashed his wrist wide open. I saw it coming and watched it as if in slow-motion as blood started squirting everywhere.

“Ahhh!” Danny shouted. Even in pain, Danny’s voice was oddly soft-spoken considering his size—kind of like Mike Tyson’s.

“Holy shit!”

“Fuck!”

“Danny’s fucked up!”

Danny lived just around the corner, so two of us held our hands over his wrist as blood kept squirting out between our fingers as we walked him home.

We got to his porch and rang the bell. His mom came to the door and we showed her Danny’s wrist. She looked at us unfazed, in disbelief.

“What the fuck do you want me to do about it?” she said, and slammed the door.

We didn’t know what to do; by this time Danny’s face was pale. We didn’t even know where the nearest hospital was. We walked him back down the street, blood still spurting all over us, and flagged down the first car we saw.

I stuck my head in the window. “Hey, my friend is bleeding to death, can you take him to the hospital?” I said hysterically. “He’s gonna die!” Luckily the lady driving was a nurse.

She put Danny in the front seat and we followed her car on our bikes. When he got to the emergency room, Danny didn’t have to wait; blood was pumping out of his wrist like a victim in a horror movie so they admitted him immediately, as the mob of people in the waiting room looked on, pissed. The doctors stitched up his wrist but that wasn’t the end of it: when he was released into the waiting room where we were waiting for him, he somehow popped one of his newly sewn stitches, sending a stream of blood skyward that left a trail across the ceiling, which freaked out and disgusted everyone in range. Needless to say, he was readmitted; his second round of sutures did the trick.

THE ONLY STABLE ONES IN OUR GANG were John and Mike, who we called the Cowabunga Brothers. They were stable for these reasons: they were from the Valley, where the typical American suburban life thrived, their parents were intact, they had sisters, and all of them lived together in a nice quaint house. But they weren’t the only pair of brothers: there were also Jeff and Chris Griffin; Jeff worked at Schwinn and Chris was his younger brother. Jeff was the most adult of our crew; he was eighteen and he had a job that he took seriously. These two weren’t as functional as the Cowabungas, because Chris tried desperately to be like his older brother and failed miserably. Those two had a hot sister named Tracey, who had dyed her hair black in response to the fact that her entire family was naturally blond. Tracey had this whole little Goth style going before Goth was even a scene.

And there was Jonathan Watts, who was the biggest head case among us. He was just insane; he would do anything, regardless of the bodily harm or potential incarceration that might befall him. I was only twelve, but even so, I knew enough about music and people to find it a bit odd that Jonathan and his dad were dedicated Jethro Tull fans. I mean, they worshipped Jethro Tull. I’m sorry to say that Jonathan is no longer with us; he died tragically of an overdose after he’d spent years as both a raging alcoholic and then a flag-waver for Alcoholics Anonymous. I lost touch with him way back, but I saw him again at an AA meeting that I was ordered to attend (we’ll get to all of that in just a little bit), after I was arrested one night in the late eighties. I couldn’t believe it; I walked into this meeting and was listening to all of these people speak and, after a while, realized that the guy leading the meeting, the one who was as gung ho about sobriety as Lieutenant Bill Kilgore, Robert Duval’s character in Apocalypse Now, had been about surfing, was none other than Jonathan Watts. Time is such a powerful catalyst for change; you never know how kindred souls will end up—or where they might see each other again.

Back then, those guys and I spent many an evening at Laurel Elementary School, making very creative use of their playground. It was a hangout for every Hollywood kid with a bike, a skateboard, some booze to drink, or some weed to smoke. The playground had two levels connected by long concrete ramps; it begged to be abused by skaters and bikers. We took full advantage of it by deconstructing the playground’s picnic tables to make them into jumps that linked the two levels. I’m not proud of our chronic destruction of public property, but riding down those two ramps and launching over the fence on my bike was a thrill that was well worth it. As delinquent as it was, it also drew creative types, many kids in Hollywood who went on to do great things hung out there. I remember Mike Balzary, better known as Flea, hanging out, playing his trumpet and graffiti artists putting up murals all the time. It wasn’t the right forum, but everyone there took pride in the scene we created. Unfortunately, the students and teachers of that school were left paying the bill and cleaning up the aftermath every morning.

Slash jumping out at the track on his Cook Bros. bike.

The principal unwisely decided to take matters into his own hands by lying in wait to confront us one night. It didn’t go over well; we kept taunting him, he got too worked up, and my friends and I got into it with him. It got out of hand so quickly that a passerby called the cops. Nothing scatters a pack of kids like the sound of a siren, so most of those present escaped. Unfortunately, I wasn’t one of them. Another kid and I were the only two who were caught; we were handcuffed to the handrail in the front of the school, right on the street, on display for all to see. We were like two hogtied animals, going nowhere and none too happy about it. We refused to cooperate: we cracked wise, we gave them fake names, we did everything short of oinking at them and calling them pigs. They kept asking and did their best to scare us, but we refused to reveal our names and addresses, and since twelve-year-olds don’t carry ID, they were forced to let us go.

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу

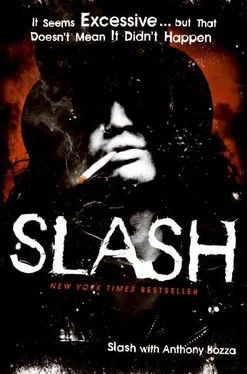

![Сол Слэш Хадсон - Slash. Демоны рок-н-ролла в моей голове [litres]](/books/387912/sol-slesh-hadson-slash-demony-rok-n-thumb.webp)