Axl and Izzy were a unit, so any other players coming into their band had to work well with both of them, and Izzy had left Hollywood Rose too quickly to get to know me at all. I liked Izzy. He was, after all, the first guy I met and I enjoyed his style and admired his talent. In dealing directly with Izzy, I’d have something of a buffer with Axl. Axl and I got along in so many ways but we had innate personality differences. We were attracted to each other and worked together tremendously well yet we were a study in polar opposites. Izzy (and later Duff ) would help. At the time, Izzy was enough to take the pressure off.

I showed up at Izzy’s apartment a few days later and he was working on a song called “Don’t Cry,” which I immediately took to. I wrote some guitar parts for it and we fine-tuned it for the rest of the evening. It was a cool session; we both got a lot out of jamming with each other.

We found ourselves a rehearsal space in Silverlake: Duff, Izzy, Axl, Rob Gardner, and myself. Everyone knew one another, so we started throwing songs together that evening and it just gelled quickly; it was one of those magic moments that musicians speak of where every player naturally complements the other and a group becomes an organic collective. I had never felt it that intensely in my life. It was all about the kind of music I was into: ratty rock and roll like old Aerosmith, AC/ DC, Humble Pie, and Alice Cooper. Everyone in the band wore their influences on their sleeves and there was not a bit of the typical L.A. vibe going on where the goal is to court a record deal. There was no concern for the proper poses or goofy choruses that might spell pop-chart success; which ultimately guaranteed endless hot chicks. That type of calculated rebellion wasn’t an option for us; we were too rabid a pack of musically like-minded gutter rats. We were passionate, with a common goal and a very distinct sense of integrity. That was the difference between us and them.

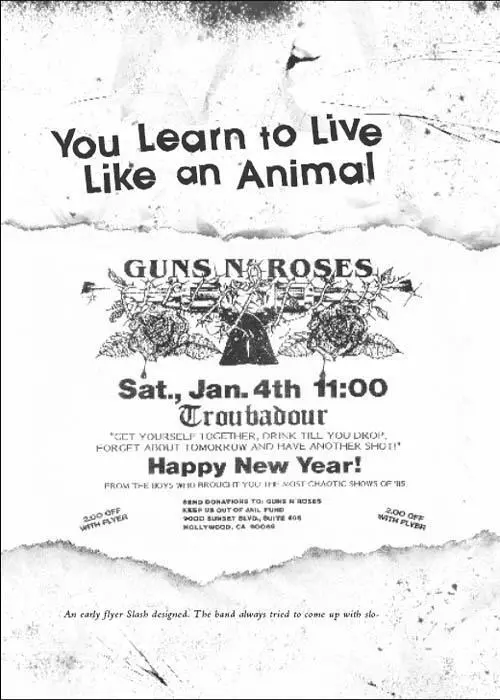

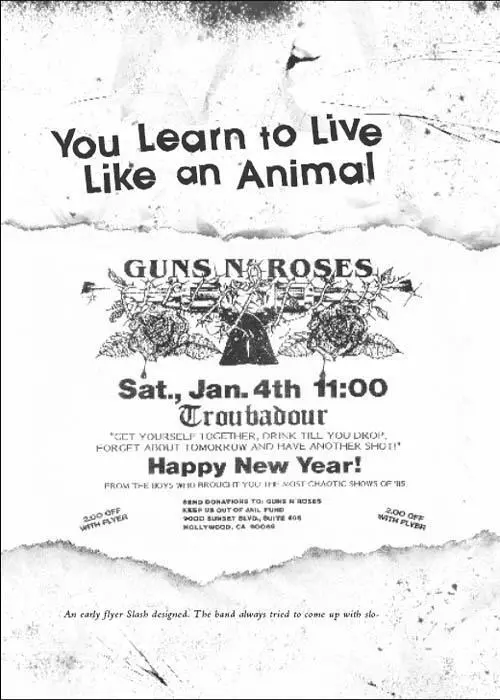

6. You Learn to Live Like an Animal

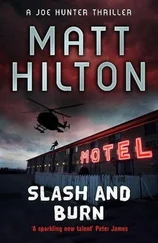

An early flyer Slash designed. Te band always tried to come up with slo—

We weren’t exactly the type of people who took no for an answer. We were much more likely to give no for an answer. As individuals, each of us was street-smart, self-sufficient, and used to doing things his way only—death before compromise. When we became a unit that quality multiplied by five because we’d have one another’s backs as fiercely as we’d stood up for ourselves. All three of the common definitions of the word gang definitely applied to us: 1) we were a group who associated closely for social reasons such as delinquent behavior; 2) we were a collection of people with compatible tastes and mutual interests who gathered to work together; and 3) we were a group of persons who associated for criminal or other antisocial purposes. We had a gang’s sense of loyalty, too: we only trusted our oldest friends, and found everything we needed to get by in one another.

Our group willpower drove us to succeed on our own terms but never made the ride any easier. We were unlike the other bands of the day; we didn’t take kindly to criticism from anyone—not our peers, not the charlatans that tried to sign us to unfair management contracts, not the A&R reps vying to hand us a deal. We did nothing to court acceptance and we shunned easy success. We waited for our popularity to speak for itself and for the industry to take notice. And when it did, we made them pay.

We rehearsed every day, working up songs that we knew and liked from one another’s bands, like “Move to the City” and “Reckless Life,” which were written by some version or another of Hollywood Rose. We had a piece of shit PA, so we composed most of the music without Axl actually singing with us. He’d sing under his breath and listen and provide feedback on what we were talking about in the arrangements.

After three nights we had a fully realized set that also included “Don’t Cry” and “Shadow of Your Love,” and so we unanimously decided that we were now fit for public consumption. We could have booked a gig locally, because, collectively, we all knew the right people, but no, we decided that after three rehearsals, we were ready for a tour . And not just a long weekend tour of clubs close to L.A.; we took Duff up on his offer to book us a jaunt that stretched from Sacramento all the way up to his hometown of Seattle. It was completely improbable but to us it seemed like the most sensible idea in the world.

We planned to pack the gear and leave in a few days, but our zeal scared the shit out of our drummer, Rob Gardner, so much that he more or less quit the band on the spot. It didn’t surprise anyone because Rob could play well enough but he didn’t fit in from the start; he wasn’t of the same ilk, he wasn’t one of us: he just wasn’t the sell-your-soul-for-rock-and-roll type. It was a polite departure—we couldn’t imagine anyone who had played those last three rehearsals not wanting to tour the coast as an unknown band with nothing but our gear and the clothes on our backs, but we accepted his decision. We would not be stopped, however, so I called the one drummer that I knew who would leave that night if we asked him to: Steven Adler.

We watched as Steven set up both of his silver-blue bass drums and loosened up with a few typical double-bass fills at rehearsal the next day. His aesthetic touchstones were off, but it wasn’t an insurmountable problem. It was a situation rectified in a typically Guns fashion: when Steven ducked out to take a piss, Izzy and Duff hid one of his bass drums, a floor tom, and some small rack toms. Steven returned, sat down, and started counting in the next song before he realized what was missing.

“Hey, where’s my other bass drum?” he asked, looking around as if he’d dropped them on the way to the bathroom or something. “I came here with two… and my other drums?

“Don’t worry about it, man. You don’t need them, just count off the song,” Izzy said.

Steven never got his extra bass drum back and it was the best thing that ever happened to him. Of the five of us, he was the most conventionally contemporary, which, all things considered, lent a key element to our sound—but we weren’t going to let him hammer that point home all night long. We bullied him into being a straight-ahead, 4/4 rock-and-roll drummer, which complemented and easily locked in with Duff’s bass style, while allowing Izzy and me the freedom to mesh blues-driven rock and roll with the neurotic edge of first-generation punk. Not to mention what Axl’s lyrics and delivery brought to it. Axl had a unique voice; it was brilliant in range and tone, but even though it was often intense and in your face, it had an amazingly soulful, bluesy quality to it because he had a choir background from singing in church when he was in grade school.

By the end of his tryout, Steven was hired and the original Guns N’ Roses lineup was locked and loaded. Duff had booked the tour; all that we needed was wheels. Anyone who knows a musician well, successful or otherwise, knows this: generally, they are adept at “borrowing” from their friends. It took one phone call and very minor convincing for us to enlist our friends Danny and Joe, whose car and loyalty we made use of very regularly. To sweeten the deal, we christened Danny our tour manager and Joe our roadie and the next morning drove Danny’s weathered green tank of an Oldsmobile out to the Valley to pick up a U-Haul trailer that we filled with the amps, guitars, and drum kit.

Seven of us packed into this mid-seventies Olds and set out on what I don’t think anyone but Duff realized was a trip of over a thousand miles. We were outside of Fresno, two hundred miles from L.A. and two hundred short of Sacramento, when the car broke down. Danny wasn’t the type of guy to have splurged for AAA, so luckily we broke down within pushing distance of a gas station, where we discovered that it would take four days to get the necessary parts to fix a beast that old. At that rate, we wouldn’t make any of the shows.

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу

![Сол Слэш Хадсон - Slash. Демоны рок-н-ролла в моей голове [litres]](/books/387912/sol-slesh-hadson-slash-demony-rok-n-thumb.webp)