Boyfriend always had a darkroom in his bathroom, and toward the end of their relationship I discovered that he was freebasing cocaine in there all night long while “working.” It wasn’t always all bad over there, but once freebasing suddenly popped up in Boyfriend’s life, it proceeded to promptly halt his career—taking his relationship with my mom down with it. Boyfriend was tortured; he was miserable and misery loves company, so although I wasn’t fond of Boyfriend at all (and he knew it), he was determined to drag me along for the ride. We’d freebase together, then go out into the neighborhood and wander into other people’s garages. Usually we’d steal used furniture, old toys, and whatever odds and ends it seemed like the family had discarded. One of the items we found was a red couch that we carried all the way back to our house; we then spray-painted it black and put in the den. I can’t imagine what Ola thought when she woke up the next morning. I have no idea actually, because she never mentioned it. In any case, after our adventures, Boyfriend would keep at it, basing all morning and, I suppose, all day. I’d duck into my room by 7:30 a.m., pretend to sleep for an hour, then get up, say good morning to my mother, and head off to school as if I’d just had a good night’s sleep.

My mom had insisted that I live with her and Boyfriend because she disapproved of the conditions I’d been subjected to over at my dad’s place. Once my dad had acclimated to their separation, he got it together to rent an apartment where his friend Miles and a group of my parents’ mutual acquaintances lived. It seemed like everyone in that scene drank a lot, and my dad was dating a number of women, so my mother didn’t think it was a good environment for me. My dad dated a woman named Sonny on a regular basis during that period. Life had not been kind to Sonny; she’d lost her son in a horrible accident and though she was really sweet, she was really screwed up. She and my dad spent a lot of time together drinking and fucking. So for a while there, while I lived with Mom, I saw Dad only on weekends, but when I did, he always had something interesting waiting for me: some unusual dinosaur model or something more technical, like a remote controlled airplane that you had to build from scratch.

Later on, I saw more of him once he moved into an apartment on Sunset and Gardner, in a building of studio apartments with a shared bathroom. His art buddy Steve Douglas lived just down the hall. On the first floor was a guitar store, though at the time I hadn’t yet picked up the habit. My dad’s art studio filled the entire room, so he’d built a loft to sleep in on the far wall and I lived there with him for a while when I was in seventh grade, just after I got kicked out of John Burroughs Junior High for stealing a load of BMX bikes—but that is a story not worth telling. In any case, for that brief period I attended Le Conte Junior High, and since my dad didn’t drive, I walked the five miles to school and back each day.

I’m not quite sure what Dad or Steve did for money. Steve was an artist as well and as far as I could tell, all they did was spend their days drinking and their nights painting for their own benefit or talking about art. One of my more entertaining memories from that period involved Steve’s old-fashioned medicine bag full of vintage porn that he caught me looking at one day.

His place and our place were basically shared space, so it was entirely normal for me to wander down to his studio whenever I wanted to. One day he walked in and found me looking through his treasure chest of porn. “I’ll make you a deal, Saul,” he said. “If you manage to steal that bag out from under my nose, you can keep it. Think you’re up to it? I’m pretty quick; you’d better be good.” I just smiled at him; I’d already devised a plan to make it mine before he challenged me. I lived down the hall—compared to what I was already doing out in the world in terms of theft, this wasn’t much of a heist.

A couple of days later I went over to Steve’s place looking for my dad and at the time they were so engaged in conversation that they didn’t even notice that I’d come in. It was the perfect opportunity; I grabbed the bag, walked out, and stashed it up on the roof. Unfortunately it was a short-lived victory: my dad ordered me to give it back once Steve realized that it was gone. It’s too bad; those magazines were classics.

There were periods throughout my childhood when I insisted to my parents that they weren’t my parents, because I honestly believed that I’d been kidnapped. I also ran away a lot. One time when I was preparing to run away, my dad actually helped me pack my suitcase, which was a little plaid bag he’d bought me in England. He was so understanding about it and so helpful and kind that by doing so, he convinced me to stay. That kind of subtle reverse psychology is one of the traits of his that I hope I’ve inherited, because I’d like to use it on my kids.

I’D SAY MY BIGGEST ADVENTURE WAS the day I took off on my Big Wheel when I was six years old. At the time we lived at the top of Lookout Mountain Road and I rode it all the way down to Laurel Canyon, then all the way down Laurel Canyon to Sunset Boulevard, which, all in all, is just over two miles. I wasn’t lost, I had a plan: I was going to move into a toy store, and live there for the rest of my life. I guess I’ve always been determined. Sure, there were many times that I wanted to get away from home as a kid, but I have no regrets about how I was raised. If it had been any bit different, if I’d been born just one minute later, or been in the wrong place at the right time or vice versa, the life that I’ve lived and come to love would not exist. And that is a situation that I wouldn’t want to consider in the slightest.

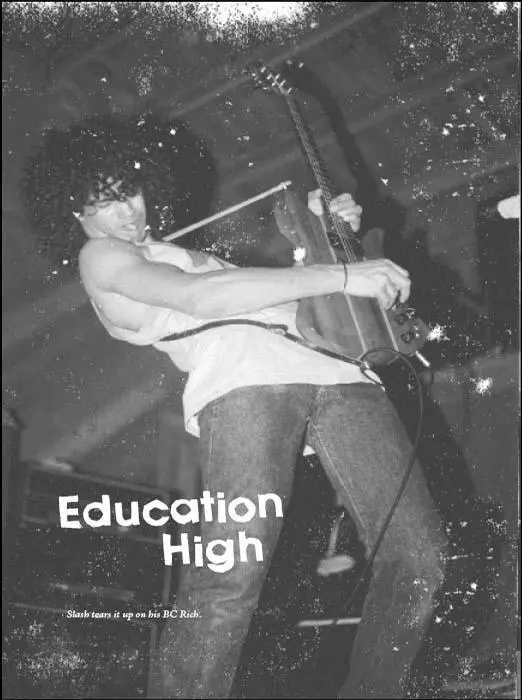

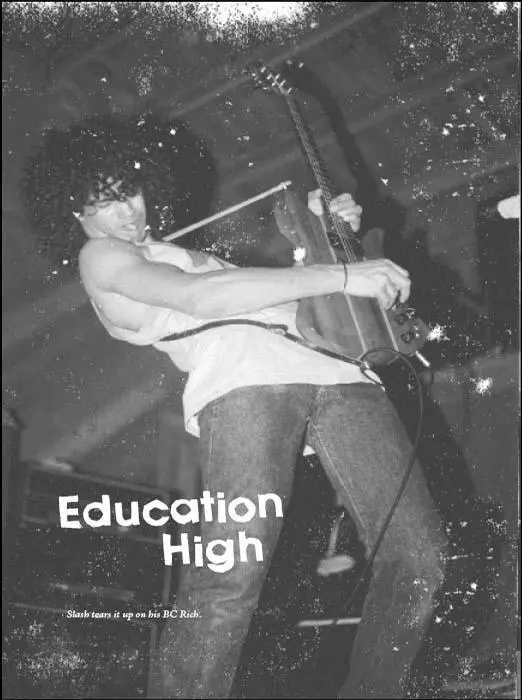

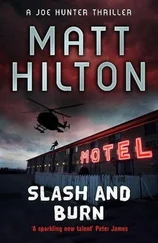

Slash tears it up on his BS Rich.

Institutional hallways are all the same, they’re just different colors. I’ve seen the inside of several rehab centers, some more upscale than others, but the clinical sobriety of their walls was identical. All of them were predominantly white and plastered with optimistic slogans like “It’s a journey, not a destination” and “One day at a time.” I found that last one ironic considering the road that Mackenzie Phillips has been down. The rooms were generic backdrops engineered to inspire hope in people from every walk of life, because, as those who have been there know, rehab is a more accurate cross section of society than jury duty. I never learned much from “group”; I didn’t really make any new buddies in rehab and I didn’t take advantage of multiple opportunities to make new drug connections either. After I’d spent days in bed with my body in purgatorial knots, unable to eat, speak, or think, I wasn’t up for small talk. To me, the communal aspect of rehab was forced—just like high school. And just like high school, I didn’t fit in. Neither institution taught me their intended lessons, but I learned something important from each of them. On my way back down their hallways toward the exit, I was confident that I left knowing exactly who I was.

Ientered Fairfax High in 1979. It was an average American public high school—linoleum floors, rows of lockers, a courtyard, a few around-back spots where kids have snuck cigarettes and done drugs for years. It was painted a very institutionally neutral light gray color. There was a good spot to get high out by the football field, there was also a continuation school on the other side of campus called Walt Whitman, where all the real fuck-ups went, because they had to. That seemed like the end of the line, so although it was more interesting, even from afar, than the normal campus, I tried to stay away from that place as much as possible.

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу

![Сол Слэш Хадсон - Slash. Демоны рок-н-ролла в моей голове [litres]](/books/387912/sol-slesh-hadson-slash-demony-rok-n-thumb.webp)