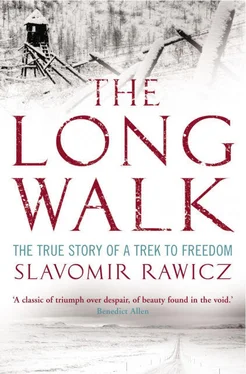

For twenty-four hours we lived out the full force of the blizzard, the lorries hopelessly snowed in. Only the fires and the still-functioning field kitchen preserved us. The tufts of hardy broad-bladed grass, a roadside feature all through the march, bent over, swung and gyrated under the whiplash of the wind with a constant swishing and whistling. The snow hissed and sizzled as it drove against the fires. We stamped around to save our frozen feet from frostbite, huddled our hands in our fufaikas, damned the storm and wondered how we were to get out of this place.

When the wind eventually abated and the snow began to thin, the first impression I had was of the silence. It was possible again to hear clearly ordinary camp noises, to pick up the murmur of low conversation. There was still a sharp wind, keening quietly through the trees, but its sound was nothing to the hammering whine of the blizzard which had assaulted us through the long hours. I do not remember just how long we stayed under the lee of the woods. It seemed a long time. Maybe it was no more than two days. At any rate, there came a morning which was clear with that extraordinary clarity one gets on a fine Siberian winter day, a very cold day when the breath is expelled in clouds of steam, when the eye can see for vast distances. A knot of Russian officers stood talking, occasionally looking back in the direction whence we had come, from time to time glancing at their watches. There was an air of waiting for something to happen and because we had not the remotest idea of what the next move could be, we were all stirred with curiosity and a growing excitement.

We heard before we saw what we were waiting for — the sound of men’s voices yipping and yelling in the distance. Everyone turned in the direction of the sounds. We stood looking for perhaps five minutes before the first of them came over the ridge about a quarter of a mile away. We shouted our surprise and excitement. Reindeer! Reindeer and sledges! Dozens of them. Reindeer, two, three and even four to a sled in line ahead, driven by little brown men, barely five feet tall, with smooth Mongoloid faces, the nomadic Ostyaks, the primitive herdsmen of the Siberian steppes. The novelty of it all was like a tonic. Men came out of their discomfort and apathy with shouting and laughter. Near me was a man who jumped up and down and kept saying over and over again, ‘Well, I’m damned. Look at that lot.’ New faces, new sights, new sounds. The cries of the Ostyaks, the unharnessing of the reindeer, the hobbling of the forefeet and the setting of the animals free to feed and look for their staple diet of moss under the covering of the thick snow — all these activities absorbed our interest. It was all new in surroundings and conditions where we thought there could be nothing new. The man near me was still talking to himself in a tone which suggested, ‘What will they think of next?’

It took the Ostyaks only a short time to release their reindeer from the primitive harness, a neck collar of reindeer hide, thong-fastened to two long, curved shafts which swept down and back to form the runners of the simple, wood-platformed sled, on which were sable and other skins. The little men had brought food with them in small sacks and they joined us round the fire as we received our morning issue of bread and coffee. They wore warm skin clothing. They looked at us with pity, their sharp, twinkling eyes puckered into slits as is the manner of men who spend their lives facing hazards of the world’s worst weather.

I spoke to one of them in Russian. He might have been sixty, but it is difficult to tell with these Mongol types. He told me they had been visited at their winter camp by the Red Army men and they were not pleased to be sent on this trip. He thought they had made a fast journey of nearly a hundred miles to meet us. They had brought soldiers with them, a couple to each sledge. He told me about reindeer, that you could not ride on their backs because they were weak there, but their necks and the humps of their shoulders were very strong and an Ostyak could vault up there with the help of his long pole, the gentle goad they used in driving the sledge, and ride without strain or fatigue to the animal. He told me his name, but to a mind used only to Western and Russian names it left no impression on the memory.

On several occasions I was to talk to this little man. He would quietly seek me out. He had not a great deal to say. He would think hard and with obvious effort to put over any idea. But he called us, as did all the Ostyaks, the Unfortunates. Traditionally, from the time of the Czars we were, to his people, the Unfortunates, the prisoners of a régime which always sought to wrest the riches of Siberia by the use of unpaid labourers, the political prisoners who could not fit in the framework of successive tyrannies.

‘We are your friends always,’ he once said to me. ‘Since a long time ago, before me and my father and his father before him, we placed outside our dwellings at night food for the wandering Unfortunates who had fled away from their camps and knew not where to go. In my time, too, because I am becoming an old man, I remember the placing of food.’

‘These men like us,’ I said, ‘have they always tried to escape from the Russians?’

‘Always men who are young and strong and hate slavery have tried to escape,’ said the Ostyak. ‘Perhaps you will try to escape, I think.’

Escape. I turned the word over in my mind and knew that it had been with me as an idea since the day I left the Lubyanka. Yes, old Ostyak, I thought, all men who are young and strong and do not want to die must think of escape. Step to the right, step to the left… the Russians knew it too. But only a madman could entertain any serious hopes of a break on this wintry trek to the North. If a man were not shot — and there were chances of getting away as security slackened in the last stages, with the soldiers as preoccupied as anyone in keeping fit and alive and completing the march — there could only be death in attempting to live off this country in winter, weak and half-starved as we already were. Nevertheless, the old reindeer man left me with one thought I was to cherish later: men did attempt to escape.

The old man talked of the way of life of his people, the animals whose skins were so valuable to them, about the reindeer which they looked after with such care. ‘Once,’ he said, ‘we were allowed to shoot animals with a gun, but now the Soviets will not let us use guns and we catch all our animals in traps.’

The day we moved off behind the sledges there was some laughter at the protests of the Ostyak whose four-reindeer team had been selected to draw the field kitchen, which was only a wood-fired steel boiler and oven combined. He swore that his animals and his light sledge would never be able to cope with so difficult a load. The Russian cooks went stolidly on with the job and we watched with amused sympathy for the Ostyak but with a tinge of concern lest his fears became justified. It was all right, though. We trudged off, our chains now fastened to the sledges, and the field kitchen, to our relief, came too. Some of the soldiers stayed with the lorries and I was sorry to see those big, dependable vehicles left behind. What happened to them I do not know. Perhaps they were able to turn back, or the kolhoz tractors came to their rescue.

The novelty of marching behind the wagging rumps of reindeer and watching their antlered heads swinging along the trail never quite wore off. We learned that by gently leaning back on the chain all together we could slow the pace considerably. We picked up that trick in a somewhat disorderly crossing of a small river bounded by steep banks. The reindeer made a great scramble of it, the guards bawled at the drivers to hold their charges to a reasonable pace and we, half-enjoying the confusion, threw our combined weight back against the speeding sledges. We got down one bank at a rush and then tore up the opposite side at a shambling trot. It took the best part of an hour to get the crazy circus back into line and ready to move again.

Читать дальше

![Джеффри Арчер - The Short, the Long and the Tall [С иллюстрациями]](/books/388600/dzheffri-archer-the-short-the-long-and-the-tall-s-thumb.webp)