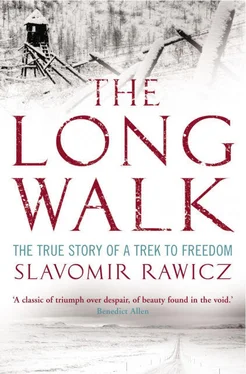

The soldiers walked down the train removing the seals and unbarring the trucks and ordering, ‘All out. The trip’s over.’

We stumbled out and a shrieking, whipping wind, and a sub-zero temperature made us gulp and gasp and cling to the small shelter afforded by the trucks. In a few minutes ears became icy cold, noses purple-red and eyes streamed tears. We shivered, all of us, uncontrollably. It was the second week in December and Siberia was already fast bound in winter. We met it still clad only in a pair of trousers, canvas shoes and a thin cotton blouse. The soldiers inspected each wagon to make sure it had been cleared. Some men, seized with cramp or worse, had to be lifted down. There was some milling about, a shouting of orders, repeated again down the line to each group and we formed into a long, untidy column — a crowd of perhaps four thousand prisoners, headed, tailed and flanked by soldiers. We shambled off, heads bent against the wind, trousers soaked to the knees in the snow and slush churned up by those ahead.

The march took us five miles across country, out of sight and sound of the railway. It was typical of the whole enterprise that our resting-place was to be no haven for drooping travellers. We stopped and broke out of ranks in a vast, wind-swept potato field. Nowhere, as far as the eye could see in any direction, was there a building of any sort. The field lay under two feet of crisp snow. A few wood-burning kolhoz lorries stood around. There was a single mobile field kitchen which seemed grossly inadequate for the needs of such a mass of prisoners. The wind had jagged teeth that made me feel quite naked to its attack. Men stood in the snow and looked bleakly at one another. All the tears were not caused by the cutting wind.

The period of aimless standing around did not last long. It was urgently necessary to do something to get out of the paralysing blast of the wind. One group near me started to scrape heaped snow into a windbreak. The idea spread rapidly. Soon there was feverish toiling to make little snow-ringed compounds. Men scraped and scratched away with numb fingers down to the rock-hard black earth and when their work was done crouched down behind the windbreak.

Outside the barbed wire, about a quarter of a mile away from the edge of the field, were some woods. When the transport commandant, that apostle of Soviet culture, walked round later in the day, spokesmen from some of the groups asked him if we could be allowed to gather branches to cover the freezing ground. He gave permission. The prisoners had automatically held together in their truck communities. A few volunteers from each group were formed up and under armed escort made several trips to the woods, returning with armfuls of small twigs and branches which were carefully spread out on the ground. Men were then able to stretch out below the level of the snow heaps and escape the full impact of the wind. Even so, it was only a barely tolerable position as we huddled tightly together. Food was doled out, about one pound of bread per man per day, and, remarkably, the food kitchen managed to produce two steaming tin mugs of unsweetened ersatz coffee a day for each man.

We spent three days in the potato field, in the course of which batches of hundreds more prisoners joined us. Some of these were Finns. Now and later they were unmistakable. They always clung tenaciously together in a solid racial group. When the assembly had been completed there were not fewer than five thousand men in the field, all wondering what was going to happen next and fearfully speculating on what might be in store. Events were to justify the worst of our fears.

On our camp followers, the lice which had lived on and with us from the prisons of Western Russia, the potato field inflicted heavy casualties. Their warm hiding-places on our bodies exposed to the lash of that all-pervading blast, they dropped off or were easily picked off, and died. We did not mourn them. We were in little shape to act as hosts. They might have fared better if they could have stuck it out until the third day — a memorable day indeed.

The kolhoz lorries, with their wood-fuelled gas-generator engines, drove in on that third day and the soldiers ran round. We felt something unusual was about to happen but we could never in our most hopeful dreams have guessed what it was. The word rippled out from those closest to the lorries, ‘Clothes! New clothes.’

And new clothes it was. It took hours to make the distribution, but when it was over each man had exchanged his flimsy rubashka for the Russian winter top garment, the fufaika, a thigh-length, buttoned-to-the-throat, kapok-padded jacket.

With the jackets came a pair of padded winter trousers and stout rubberised canvas boots, laced to a point a few inches above the ankle. The boots were available in three sizes only — small, medium and large. No attempt was made to give a man the size he needed. If he were lucky they fitted. If not, he exchanged his too-small or too-large boots with someone else who had the opposite kind of misfit. I was one of the lucky ones. My issue fitted. Our old blouses and trousers were all carefully collected. The excitement was wonderful. Men’s faces glowed. They hurried and fumbled to get into their handsome new jackets. They called out to one another, parading around. And those dear old jokers, who had been almost silent since we came to the potato field, gave us a mannequin display, hands on hips and beards flying in the wind. It is a laboured truism that all things and experiences are comparative. By all normal standards we were still abjectly dressed for a Siberian winter, but the additional warmth we felt from our fufaikas was extraordinary.

On the fourth day of our stay in the potato field, the issue of winter clothing was completed. We were each handed two pieces of linen which the soldiers explained were for wrapping up the feet inside our boots. A few of the men in our truck group knew about these ‘socks’ and how best to wind them, not too tightly, around the feet to stave off frostbite. There were little demonstrations all over the field.

Into the compound drove a whole convoy of some sixty powerful lorries, each with an Army driver accompanied in the cab by another soldier as driver’s mate. They were heavy duty vehicles requisitioned from the collective farms for hundreds of miles around and had painted on their sides the names of the various kolhozi. Just behind the cabin they carried tall, cylindrical gas generators, the fuel for which was eight-inch lengths of birch and ash, known to the Russians as churki. This wood, plentifully available throughout well-forested Siberia, was a cheap and efficient substitute for precious motor spirit and solved one of the many Russian transport and distribution problems. Clipped into brackets on the lorry sides was an assortment of spades and pickaxes. The load-carrying bodies were open to the weather. Apart from their odd-looking gas generators, they looked like the normal commercial Western three-tonner.

As we watched them bumping and rolling in, the orders started to fly and we knew that the last stage of our journey was about to begin. For many of those jostling around it would be the last stage of any journey they would know on this earth.

ON THAT last day in the potato field there was an air of some big — and for the five thousand prisoners, ominous — event ahead, some major Russian transportation enterprise. The soldiers were in battalion strength, hooded in balaclavas, wearing warm sheepskin gloves and each carrying his distinctive khaki sack slung across the back and held in place by a piece of string. There were at least fifty lorries parked in a long, well-spaced line. They were open and mounted machine-gun platforms against the drivers’ cabins. If the issue of new warm clothing had not been enough warning, the presence of so many troops and vehicles removed any doubt that a fresh ordeal lay ahead.

Читать дальше

![Джеффри Арчер - The Short, the Long and the Tall [С иллюстрациями]](/books/388600/dzheffri-archer-the-short-the-long-and-the-tall-s-thumb.webp)