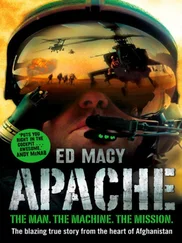

Taff had a big smile, an eight-man arming team, many thousands of cannon rounds, hundreds of rockets, over twenty missiles, two Apache pilots and over forty million pounds’ worth of helicopter under his command and control. It was a lot of responsibility for a corporal who got paid the same as our squadron clerk.

‘All the blanks are out and the tee-fifty pin is stowed, sir.’

The small metal T50 pin sat under a cover on the Apache’s nose, just in front of the co-pilot gunner’s window. It had a long red and white flag attached to make sure we didn’t take off with it still in place. With the pin removed, the yellow-and-black, dog-bone shaped initiation device – the same as the ones in both cockpits – was automatically armed. Their job was to initiate the detonation cord threaded round the side windows, blasting both canopies fifty metres. In an emergency, it would be Taff’s job to initiate the explosion if we couldn’t.

Billy yelled his thanks.

‘I’m going in the front, Ed – jump in and get her started.’

Billy began to run round the Apache checking that all the blanks that kept dust and debris from every orifice had been removed and she was ready to fly.

I was still trying to take in what he’d said. We had fully briefed the mission, monitored whatever we could of the battle and authorised the flight, gearing everything towards me being in the front seat as the gunner and commander, and Billy in the back seat as the pilot and captain.

Every military flight required prior authorisation signed by both the aircraft captain and the authorising officer. It declared the exact conditions of the flight: which Apache was being flown, the flight date, who was captain, who was in which seat, which survival jacket they were wearing for escape and evasion purposes, the ETD and the ETA. It then outlined the mission: takeoff location, route, landing location, mission number, outline mission details, any limitations (like the minimum height), and if there were any fuel restrictions. If any of these details were altered, the authorising officer had to be informed and the authorising sheet amended before the flight.

I was puzzled by the late change, but the flight was on Billy’s authorisation as he was captain. I wasn’t in a position to order him into the back seat as briefed. I could have refused to fly until we went back to Plan A or changed our authorisation – but the time for that had long since passed. I wasn’t being anal. If we got shot down, the authorisation sheet would wrongly identify which of us was where – and that could have serious repercussions in the post-crash, escape and evasion phase.

I knew Billy would have some reasonable justification – but that didn’t stop me wondering if he just wanted to go in the front so he could do the shooting. Either way, there was no time to argue. We needed to get off the ground asap, then tell Ops and have the appropriate discussion when we got back.

It was only early summer, but the weather was unbelievably hot and taking its toll on our troops. Everyday tasks appeared a hundred times more difficult and ten times slower to perform. The sun only seemed to have one goal – to punish us for being somewhere we couldn’t call home.

My combats were already damp with sweat and clung uncomfortably to my body. As I climbed up the blisteringly hot skin of the starboard side of the aircraft I noticed that Billy was also struggling. Grape-sized beads of sweat tumbled down his face, which was contorted with concentration.

I felt much older than my forty years in this heat, but my brain felt like an eighteen-year-old’s, buzzing with adrenalin and fired up by the prospect of the impending battle. I knew Billy felt the same; we didn’t need to discuss it. We were both WO1s and had a shitload of military experience between us.

656 Squadron Army Air Corps was the first and currently the only Apache squadron in the British Forces capable of deploying to a combat zone. We lived to outwit the enemy and survive to fight another day. It was utterly addictive and nothing could compare to it. At that moment I genuinely believed it would be better to die today at the hands of the Taliban than to rot into old age, swapping war stories in my retirement home.

Today would be fun.

I heaved open the door and clicked it into place above the entrance to the rear cockpit. I stretched across, inserted the ignition key and twisted it to On.

The beast began to stir as it sucked life from the battery and the relays kicked over. The Up Front Display sparked up and confirmed that there was full fuel – no faults so far.

The UFD also had a digital clock fed by two GPSs:

13:10:08… 13:10:09… 13:10:10…

SUNDAY, 4 JUNE 2006

1310 hours local

CO 3 Para lands in his Chinook at the now quiet and well-protected target compound. He orders Patrols Platoon to get out of the close country and move south-west to more open ground where they can employ their .50 cals without the restrictions of alleyways and orchards.

Still kneeling beside the cockpit, I bellowed, ‘Pylons… stabilator… APU clear?’

We were now officially late. I hoped 3 Flight could push their fuel a bit longer.

Taff checked there was no one near the weapons pylons, the slab-like stabilator, or within range of the hot exhaust gases the Auxiliary Power Unit would be spitting out very shortly.

In his broad Welsh accent he reported back, ‘Pylons, stabilator and APU clear-clear to start the APU.’

The APU was the Apache’s third engine, only used to get all the systems up and running and to provide compressed air with which to start the main engines.

Back in the UK it used to take us about an hour to start an Apache and be ready to taxi. It could take as little as forty-five minutes if you cut corners and all went well. Out here, in a rush, on a good day, with no snags and if the TADS cooled quickly enough, it could be done in as little as twenty minutes, but between thirty and forty was more usual. With the APU running, to all intents and purposes the Apache was ready to go. We could sort out any problems and get the TADS and PNVS ice cold so it could see properly. All we needed to do then was switch on the main engines and pull power – a two-minute job.

Stretching back across the cockpit I lifted a small clear cover and pushed the recessed button beneath it. The APU was startled into life. Within a few seconds the acronym on the button glowed green, and it was soon screaming away at full power.

I flipped my helmet onto my head, making sure my ears weren’t folded, and then buttoned the chinstrap tight. A bent ear now would drive me to distraction later.

I grimaced as the internal harness pushed down on the weeping egg on the top of my head.

I dragged my life-support jacket from my seat and pulled it on. It felt cumbersome and tight as I zipped it up, and became even more uncomfortable when I slipped a triangular armoured plate into the sheath on the front.

The ‘chicken plate’ was designed to shield the vital organs within the chest cavity from bullets and shrapnel. As I pulled up the outer zip holding it in place, it pressed heavily on my bladder, making me even more uncomfortable and irritable than before.

It fitted so tightly that it was impossible to take an extra-deep breath. But if it were slacker it would become a snag hazard if I had to be dragged from the cockpit in an emergency. I tried to look on the bright side: it would stop my organs spilling out if I were shot. The pressure would stem the flow of blood and keep me conscious for a few more valuable seconds.

The heat was getting to me good style; I could actually smell it. The cockpit stank like a workshop. The wiring, glues, resins, metals and a whole host of other materials came under immense temperatures in the glass cocoon.

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу