They sat on the grass of the towpath, leaning their backs against the wall, watching the barges go by. Mary said she was tongue tied. She felt overwhelmed by this kind, handsome youth who seemed to like her, and she couldn’t think of a thing to say, even though for four or five days she had been longing for someone to talk to.

“He talked all the time, and laughed, and threw bits of bread to the sparrows and pigeons, and called them ‘my friends’. I thought someone who is friends with the birds must be very nice. Sometimes I couldn’t understand quite what he was saying, but the English accent is different to the Irish accent, you know. He told me he was a buyer for his uncle, who had a nice café in Cable Street and who sold the best food in London. We had such a lovely meal sitting there on the towpath in the sunshine. The rolls were delicious, the apple pies were delicious, and the chocolate cake was out of this world.”

She leaned back on the stone wall, and sighed with contentment. When she woke up the sun was behind the warehouse, and his jacket was over her. She found that she was leaning on his shoulder.

“I woke up with his strong arm around me, and his beautiful brown eyes looking down at me. He stroked my cheek, and said, ‘You’ve had a nice big sleep. Come on, it’s getting late. I had better take you home. Your mother and father will wonder what has happened to you.’

“I didn’t know what to say then, and he didn’t talk either. After a bit, he said: ‘We must get going. What will your mother think, you being out with a stranger all this time?’

“Me mam’s a long way off in Ireland.’

“Well, your dad then.’

“Me dad’s dead.’

“You poor little thing. I suppose you are living with an auntie in London?’

“He stroked my cheek again when he said ‘you poor little thing’, and I thought I would melt with happiness. So I snuggled up in his arms, and told him the whole story - but I didn’t tell him about me mam’s man and what he’d done to me, because I was ashamed, and didn’t want him to think badly of me.”

“He didn’t say anything. For a long while he just stroked my cheek and my hair. Then he said: ‘Poor little Mary. What are we going to do with you? I can’t leave you here by the Cuts all night. I feel responsible for you now. I think you had better come back with me to my uncle’s place. It’s a nice café. My uncle is very kind. We can have a good meal and then we can plan your future.’”

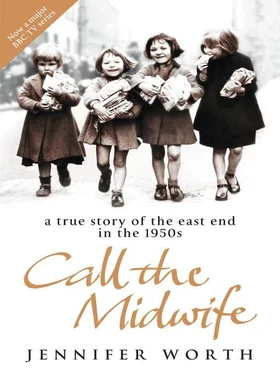

Pre-war Stepney, just east of the City, with Commercial Road to the north, the Tower and Royal Mint to the West, Wapping and the Docks to the South, and Poplar to the east, was the home of thousands of respectable, hard-working, but often poor East End families. Much of the area was filled with crowded tenements, narrow unlit alleyways and lanes and old multi-occupant houses. Often the old houses had only one tap, and one lavatory in the yard, to serve between eight and a dozen families, and sometimes a whole family of ten or more might occupy one or two rooms. The people had lived like this for generations, and were still doing so in the 1950s.

This was their inheritance and their accepted lifestyle, but after the war, things changed dramatically, for the worse. The area was scheduled for demolition, which did not actually take place for another twenty years. In the meantime, the area became a breeding ground for vice of every description. The condemned houses, which were privately owned, could not be sold on the open market to responsible landlords, so they were bought up by unscrupulous profiteers of all nationalities, who let out single, derelict, rooms for fantastically low rents. The shops were bought up in the same way and turned into all night cafés, with their ‘street waitresses’. They were, in fact, brothels, making life hell for the decent people who had to live in the area, and bring their children up in the midst of it all.

Overcrowding had always been part of the East Ender’s life, but the war made it far worse. Many homes had been destroyed by the bombing and not replaced, so people lived anywhere they could find. On top of this, in the 1950s, thousands of commonwealth immigrants poured into the country with no provision made for where they were going to live. It was not uncommon to see groups of ten or more West Indians, say, going from door to door, begging for a room to let. If they did find one, in no time at all it would be filled with twenty to twenty-five people, all living together.

This sort of thing the East Enders had seen before, and could absorb. But when it came to the blatant widespread use of their streets, their alleys and closes, their shops and houses, as brothels, it was a very different matter. Life became sheer hell, and women were terrified to go out of doors, or to let their children out. The tough, resilient East Enders, who had lived through two world wars, lived through the Great Depression of the 1930s, survived the Blitz of the 1940s, and come up smiling, were to be crushed by the vice and prostitution that descended in their midst in the 1950s and ’60s.

Try to imagine, if you can, living in a derelict building, renting two rooms on the second floor, with six children to bring up. And then try to imagine that there is a new landlord, and through threats, intimidation, fear, or genuine rehousing, one by one, all the families you have known since childhood have moved out. All the rooms of the house in which you live have been divided up and filled with prostitutes, as many as four or five to each room. The general store, which used to be the ground floor of the building, has been turned into an all-night café with noise and loud music, parties, swearing, fights, going on all night. The trade of prostitution goes on all night and all day, with men tramping up and down the stairs, and hanging around on the stairways or landings, waiting their turn. Imagine it, if you can, and imagine the poor woman who has to take her toddlers out shopping, or get the children off to school, or go down to the basement alone to get a couple of buckets of water with which to do her washing.

Many such families were on the council waiting list for rehousing for as much as ten years, and the biggest families had the least chance of getting other accommodation because the council (under the Housing Act) was not allowed to put a family of ten into a four-room flat, even though the two room conditions under which they were living had been condemned for human habitation.

Into this environment came Father Joe Williamson, who was appointed Vicar of St Paul’s in Dock Street in the 1950s. He devoted the rest of his life, his considerable energies, his powerful mind and above all his Godliness, to cleaning up the area and helping the East End families who had to live there. Later, he began his work of helping and protecting the young prostitutes, whom he loved and pitied with all his heart. It was he who opened the doors of Church House, Wellclose Square, as a home for prostitutes, and this was the place Mary went the day after I had picked her up at the bus stop. I visited her there several times, and it was during these visits that she told me her story.

“Zakir put his coat around my shoulders, because it was getting chilly, and he carried my bag. He put his arm round me, and led me through the crowds of men leaving the docks. He escorted me over the road like a real gentleman, and I can tell you I felt like the greatest lady in London by the side of such a handsome young man.”

He took her down a side street off Commercial Road, which led into other side streets, each one narrower and dirtier than the last. Many windows were boarded up, others broken, others so dirty that it would have been impossible to see through them. There were very few people around, and no children played in the streets. She looked up the height of the black buildings. Pigeons flew from ledge to ledge. A few of the windows looked as if someone had tried to clean them, and had curtains. One or two even had washing hanging out on a little balcony. It looked as though the sun never penetrated these narrow streets and alleys. Filth and litter were everywhere; in the corners, the gutters, piled up against railings, blocking doorways, half filling the little alleys. Zakir carefully led Mary through all this dirt, telling her to be careful, or to step over this or that. The few other people they met were all men, and he protectively drew her closer to him as they passed. One or two of them he obviously knew, and they spoke to each other in a foreign language.

Читать дальше