* * *

On June 6, Bob Shumaker was nearing his fourth month of isolation in Room Nineteen when Owl surprised him with paper and a pen. The Camp Authority was at last permitting him to write home. He wrote two pages to his young wife in clear cursive. He explained how he’d thought about their every experience, reliving even their disagreements, and how he treasured the time they’d had together.

By good fortune, Shu was among a handful of aviators the U.S. military had clandestinely trained to use a cipher that remains classified to this day. It was, and is, intended precisely for situations such as captivity. Now, in his first letter home, he used his training to arrange his words and letters, encrypting the initials of confirmed POWs to inform U.S. intelligence whom the North Vietnamese held. Mentally composing the encrypted letter before writing it took tremendous focus, but in Room Nineteen, Shu had no distractions.

By the time Shu had written his first letter, seven other prisoners had joined him and Ron Storz in the Hanoi Hilton. With other sections of the prison full of Vietnamese civilians or being otherwise utilized, the growing American population forced the North Vietnamese to end Bob Shumaker’s solitary imprisonment. After four months—133 days—of loneliness, Shu watched his door open to reveal an American POW. From behind, a guard nudged Captain Carlyle “Smitty” Harris, USAF, into the room, then closed the door. At the sight of each other, wide smiles broke across the two pilots’ haggard faces. Several minutes later, guards ushered in Lieutenant Phil Butler from the USS Midway. Air Force Lieutenant Bob Peel followed to round out the new foursome. Shu grinned at his roommates until his cheeks hurt. Together with other Americans for the first time since their shootdowns, the men talked for nearly three straight days.

After the euphoria subsided, Butler told Shu about Operation Rolling Thunder, which President Johnson had launched in early March. He explained that the president intended the eight-week air offensive against North Vietnam to cut the insurgency’s lifelines without a costly ground campaign. The air operation had extended long past the eight-week mark; nobody saw an end in sight. More captives would arrive, and Shu suspected that the Camp Authority would separate Room Nineteen’s residents at the earliest opportunity. While he and his new roommates could converse safely in their shared room, camp policy strictly forbade communication elsewhere. Shu—the senior officer in Room Nineteen—knew they would need to exchange information covertly in the days ahead. Demonstrating exactly why the North Vietnamese would want to isolate their captives, the men of Room Nineteen collaborated and devised a plan to maintain contact.

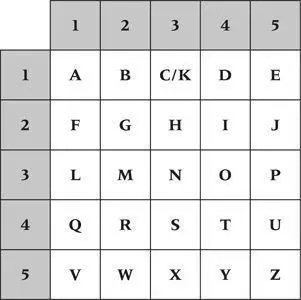

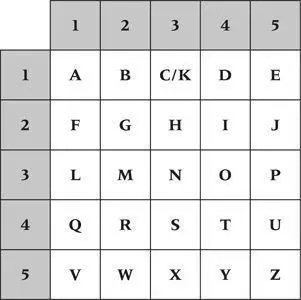

The foursome already knew Morse code, but that required sending and receiving short and long transmissions, called dots and dashes. Telegraph or signal lamp operators did this quite easily, but the men knew distinguishing between longs and shorts would prove difficult for prisoners tapping with their hands. Besides, the entire world used Morse code, including the North Vietnamese. Harris suggested an alternative. Back in the United States, he’d attended the Air Force Survival, Evasion, Resistance, and Escape (SERE) School and a course led in part by a former POW from the Korean War. During a coffee break, Harris had overheard him explain how prisoners in Korea used a code that the instructor called AFLQV, which stood for the first letter in each row of a five-by-five alphabetic grid. The phrase “American Football League Quid Victorious” served as a mnemonic to remember the grid. Harris explained that a combination of taps represented each letter of the English alphabet (except K, for which C substituted) and related to the letter’s position in the grid. A prisoner’s first set of taps represented the letter’s horizontal row. Then he’d pause briefly. His second set would denote the letter’s vertical column. The group decided that the code’s simple grid and the numerous ways one could transmit it suited the POWs’ situation in North Vietnam perfectly. The four men in Room Nineteen committed it to memory. In the conflict that was to come, few things would prove more valuable—not just to those four, but to every single American who would arrive at the Hanoi Hilton.

In July, Bob Shumaker noticed a new POW shuffling to and from the bathhouse in New Guy Village, as the prisoners in Room Nineteen had taken to calling the four cells, two main rooms, and courtyard near Hỏa Lò’s southeast corner. The new captive wore the red-and pink-striped pajamalike uniform that had begun to replace the oxfords and khakis issued to the initial wave of prisoners. The Americans called the striped outfits their “clown suits.” As the new POW crossed the courtyard, he heard a soft voice call from Room Nineteen, “Go fishing.” In the privacy of the bathhouse, he searched the drain and noticed a matchstick lying over the metal grate. When he picked it up, he found a dangling note attached. It bore the words, “If you read this, spit as you depart the latrine door.” Bob Shumaker had established contact with Commander Jeremiah Denton, Naval Academy Class of 1947. He was the thirteenth American to arrive at Hỏa Lò Prison and the new highest-ranking U.S. officer in Hanoi.

Shu found Jerry’s first reply shocking. Jerry had used a wetted burned matchstick to scribble a note explaining that the North Vietnamese had put him in leg irons; he stashed it in the bathhouse nook. “What the hell for?” Shu asked in his next drop. He had heard interrogators threaten POWs with harsh treatment, but Shu hadn’t realized they actually went through with it. He wondered how a captive could have brought such punishment upon himself. He would learn the answer as he came to discover the defiance of Jerry Denton.

* * *

Thirty-seven years before he arrived in Hanoi, Jerry Denton received his first airplane as a gift for his third birthday. His father, a hotel manager, presented him with a blue-and-gold airplane on wheels, which he rode around the Fisher Hotel in El Paso, Texas, where his family lived. He thought little more of the navy or of aviation until he saw the 1937 film Navy Blue and Gold. As he watched actors Lionel Barrymore and Jimmy Stewart navigate a football season at the U.S. Naval Academy, he realized the navy—and its academy—might help him rise above his parents’ station and provide him a path to success. As a high school senior—and as quarterback of McGill Institute’s football team, captain of its baseball and basketball teams, and its “Most Popular” student—he sought the required nomination to the academy from his U.S. representative. He did not receive a response.

With his dream hostage to bureaucracy, he enrolled at Spring Hill College, where his freshman class elected him president. The following year, he still hadn’t heard from Annapolis and decided to enter navy boot camp. One day, his commanding officer called him off the field and into his office. “Denton,” he boomed, “you’re going to Bancroft Hall!” The words meant nothing to Jerry until the officer explained that Bancroft Hall housed the Brigade of Midshipmen at the Naval Academy. Midshipman Denton walked onto the Yard in June of 1943, along with Jim Stockdale of Abingdon, Illinois, and Jimmy Carter of Plains, Georgia.

Jerry forsook Navy football so he could devote his weekends to courting his Mobile sweetheart, Jane Maury, who attended Mary Washington College in Virginia. They were married in the Naval Academy Chapel the day after he graduated. The couple left the chapel and walked beneath the Arch of Sabers, six swords held aloft by Jerry’s classmates. The ceremony initiated Jane into a world where she would see her husband excel as an officer and an aviator. Like so many others, Jerry was led to aviation by his unrelenting competitiveness and high aspirations. In the fleet’s new Grumman A-6 Intruder, he would find status, freedom, and invincibility. All that ended on July 18, 1965.

Читать дальше