My uncle became sick. One morning we were sitting on the verandah when he complained he wasn’t feeling very well. In the evening he developed a fever and he lay inside, groaning. Allie and I went to a nearby shop and bought medicine, but Uncle’s fever grew worse day after day. Auntie Sallay would force him to eat, but he would vomit everything the moment she was done feeding him. All the hospitals and pharmacies were closed. We searched the city for doctors or nurses, but those who hadn’t left would not leave their homes for fear they might not be able to return to their families again. One evening I was sitting by my uncle, wiping his forehead, when he fell off the bed. I caught his long body in my arms and held his head on my lap. His cheekbones stood out of his round face. He looked at me and I could see in his eyes that he had given up hope. I begged him not to leave us. His lips were about to utter something, but they stopped shaking, and he was gone. I held him in my arms and thought about how I was going to break the news to his wife, who was boiling him some water in the kitchen. She came in soon afterward and dropped the hot water, splashing it on both of us. She refused to believe that her husband had died. I still held my uncle in my arms, tears running down my face. My entire body had gone numb. I couldn’t move from where I sat. Mohamed and Allie came in and took Uncle away from me and put him on the bed. After a few minutes, I was able to get up. I went behind the house and punched the mango tree until Mohamed took me away from it. I was always losing everything that meant something to me.

My cousins cried, asking, Who is going to take care of us now? Why did this happen to us in these difficult times?

Down in the city, the gunmen fired off their guns.

My uncle was buried the next morning. Even in the midst of the madness, many people came for his burial. I walked behind the coffin, the sound of my footsteps clinging to my heart. I held hands with my cousins and Mohamed. My aunt had tried to come to the cemetery, but she collapsed right before we left the house. At the cemetery the imam read a few suras and my uncle was lowered into the hole and covered with mud. People quickly dispersed to continue their lives. I stayed behind with Mohamed. I sat on the ground next to the grave and talked to my uncle. I told him that I was sorry that we couldn’t find him any help, that I hoped he knew that I really loved him and wished he could have been alive to see me as an adult. After I was done, I placed my hands on the heap of mud and quietly wept. I didn’t realize how long I had been at the cemetery until after I had stopped crying. It was late in the evening and the curfew was about to begin. Mohamed and I ran as fast as we could back home before the soldiers started shooting.

A few days after my uncle was buried, I was finally able to make a collect call to Laura. I asked her if I could stay with her if I made my way to New York City. She said yes.

“No. I want you to really think about this. If I make my way to New York, can I stay with you at your house?” I asked again.

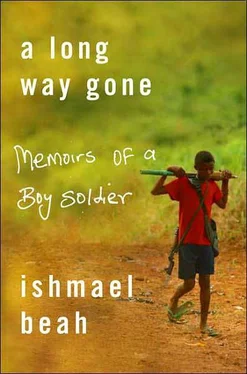

“Yes,” she said again, and I told her that “I would visualize it” and would call her when I was in Conakry, the capital of Guinea, the one neighboring country that was peaceful and the only way out of Sierra Leone at that time. I had to leave, because I was afraid that if I stayed in Freetown any longer, I was going to end up being a soldier again or my former army friends would kill me if I refused. Some friends who had undergone rehabilitation with me had already rejoined the army.

I left Freetown early in the morning of the seventh day after my uncle passed away. I didn’t tell anyone that I was leaving except Mohamed, who was to relay my departure to my aunt after she was done grieving. She had turned herself away from the world and everyone in it after Uncle’s death. I left on October 31, 1997, while it was still a little dark outside. The curfew was still in place, but I needed to leave the city before the sun came out. It was less dangerous to travel at this hour, as some of the gunmen were dozing off and the night made it difficult for the militiamen to see me from afar. Gunshots echoed in the quiet city, and the morning breeze felt harsh against my face. The air smelled of rotten bodies and gunpowder. I shook hands with Mohamed. “I’ll let you know where I end up,” I told him. He tapped me on my shoulder and said nothing.

I had only a small dirty bag containing a few clothes. It was risky to travel with a big or fancy bag, as armed men would think that you were carrying something valuable and would possibly shoot you. As I walked into the last remains of the night, leaving Mohamed standing on the verandah, I became afraid. This was becoming too familiar. I stopped next to a utility pole for a bit, exhaled heavily, and threw some angry punches in the air. I have to try to get out, I thought, and if that doesn’t work, then it is back to the army. I didn’t like thinking this way. I hurriedly walked near the gutters and took cover when I heard a vehicle approaching. I was the only civilian on the street, and I sometimes had to bypass checkpoints by either crawling in gutters or crouching behind houses. I safely made it to an old bus station that was no longer in use at the edge of the city. I was sweating and my eyelids trembled as I looked around the station. There were a lot of men—in their thirties, I presumed—some women, and a few families with children five years of age and older. They all stood in line against the dilapidated wall, some holding bundles of things and others their children’s hands.

I walked to the back of the line and sat on my heels to make sure my money was still inside my sock, under my right foot. The man in front of me kept mumbling things to himself and pacing away from the wall and back. He was making me more nervous than I already was. After several minutes of quietly waiting, a man who had been standing in line with everyone else proclaimed himself the bus driver and asked everyone to follow him. We walked farther into the abandoned station, making our way over falling cement walls into an open area where we got on a bus, which was painted dark, even its rims, so that it would blend with the night. The bus rolled out of the station, its lights off, and took the back road out of the city. The road hadn’t been used for years, so it seemed the bus was moving through bushes, as leaves and branches heavily slapped its side. It slowly galloped in the dark until the sun began to rise. At some point, we had to get off and walk behind it so that it would be able to climb a little hill. We were all very quiet, our faces tensed with fear, as we hadn’t yet safely left the city area. We got back on the bus, and about an hour later it dropped us off at an old bridge.

We paid the driver and walked across the rusty bridge two at a time, and then had to walk all day to a junction where we waited for another bus that would arrive the next morning. This was the only way to get out of Freetown without being killed by the armed men and boys of the new government, who hated it when people left the city.

There were over thirty of us at the junction. We sat on the ground near the bushes and waited all night. No one said a word to one another, as we all knew that we hadn’t completely escaped the madness. Parents whispered things in the ears of their children, afraid to let out their voices. Some people stared at the ground and others played with stones. Gunshots were faintly heard in the breeze. I sat at the edge of the gutter and chewed on some raw rice I had in a plastic bag. When will I stop running from this war? What if the bus doesn’t show up? A neighbor in Freetown had told me about this only way out of the country. So far it seemed to be safe, but I was worried, as I knew how quickly things change for the worse in such circumstances.

Читать дальше