“My name is Kristen. I am from Norway.” She extended her hand.

“I am Ishmael from Sierra Leone.” I shook her hand, and she opened an envelope of name tags and placed one on my shirt. She smiled and motioned for me to join the breakfast line as she walked away, looking for other children without name tags. I followed behind two boys who were speaking a strange language. They knew what they wanted, but I had no idea what to get or what the names of the foods were that the cooks were making. Throughout my stay, I was baffled by the food. I would simply order “the same thing,” or put on my plate whatever I’d seen others put on theirs. Sometimes I was lucky to like what landed there. That was usually not the case. I asked Dr. Tamba if he knew where we could get some rice and fish stew in palm oil, some cassava leaves or okra soup. He smiled and said, “When you are in Rome, you do as the Romans do.”

I should have brought my own food from home to hold me until I learn about the food in this country, I thought as I drank my glass of orange juice.

After breakfast we walked two blocks in the freezing weather down to a building where most of the meetings took place. It was still snowing outside, and I was wearing summer dress pants and a long-sleeved shirt. I told myself that I wouldn’t want to live in such an unpleasantly cold country, where I would always have to worry about my nose, ears, and face falling off.

That first morning in New York City, we learned about each other’s lives for hours. Some of the children had risked their life to attend the conference. Others had walked hundreds of miles to neighboring countries to be able to get on a plane. Within minutes of talking to each other, we knew that the room was filled with young people who had had a very difficult childhood, and some were going to return to these lives at the end of the conference. After the introductions, we sat in a circle so that the different facilitators could tell us about themselves.

Most of the facilitators worked for NGOs, but there was a short white woman with long dark hair and bright eyes who said, “I am a storyteller.” I was surprised at this and gave her all my attention. She used elaborate gestures and spoke very clearly, enunciating every word. She said her name was Laura Simms. She introduced her co-facilitator, Therese Plair, who was light-skinned, had African features, and held a drum. Before Laura finished talking, I had already decided that I would take her workshop. She said she would teach us how to tell our stories in a more compelling way. I was curious to find out how this white woman, born in New York City, had become a storyteller.

That same morning Laura kept looking at Bah and me. I didn’t know that she had noticed we were wearing only our light African shirts and pants and sat closer to the radiators, our hands wrapped around our tiny bodies, and every now and then shaking from the cold that seemed to have settled in our bones. In the afternoon before lunch, she approached us. “Do you have winter jackets?” she asked. We shook our heads. A painful concern passed over her face, making her smile look forced. That evening she returned with winter jackets, hats, and gloves for us. I felt I was wearing a heavy green costume that made my body bigger than it looked. But I was happy, because now I could venture outside to see the city after the daily workshops. Years later, when Laura offered me one of her winter jackets, I refused to accept it because it was a woman’s jacket. She joked with me about the fact that when she had first met me I was so cold that I didn’t care that I was wearing a woman’s winter jacket.

Bah and I became a little close with Laura and Therese over the course of the conference. Sometimes Laura would talk to us about stories I had heard as a child. I was in awe of the fact that a white woman from across the Atlantic Ocean, who had never been to my country, knew stories so specific to my tribe and upbringing. When she became my mother years later, she and I would always talk about whether it was destined or coincidental that I came from a very storytelling-oriented culture to live with a mother in New York who is a storyteller.

I called my uncle in Freetown during my second day. Aminata answered the phone.

“Hi. This is Ishmael. Could I please speak to Uncle?” I asked.

“I will go get him. Call back in two minutes.” Aminata hung up the phone. When I called back, my uncle picked up.

“I am in New York City,” I told him.

“Well,” he said, “I guess I believe you, because I haven’t seen you in a few days.” He giggled. I opened the hotel window to let him hear the sounds of New York.

“That doesn’t sound like Freetown,” he said, and was silent for a bit before he continued. “So what is it like?”

“It is excruciatingly cold,” I said, and he began to laugh.

“Ah! Maybe it is your initiation to the white people’s world. Well, tell me all about it when you return. Stay inside if you have to.” As he spoke, I pictured the dusty gravel road by his house. I could smell my aunt’s groundnut soup.

Every morning we would quickly walk through the snow to a conference room down the street. There we would cast our sufferings aside and intelligently discuss solutions to the problems facing children in our various countries. At the end of these long discussions, our faces and eyes glittered with hope and the promise of happiness. It seemed we were transforming our sufferings as we talked about ways to solve their causes and let them be known to the world.

On the night of the second day, Madoka from Malawi and I walked west along Forty-seventh Street without realizing we were heading straight into the heart of Times Square. We were busy looking at the buildings and all the people hurrying by when we suddenly saw lights all over the place and shows playing on huge screens. We looked at each other in awe of how absolutely amazing and crowded the place was. One of the screens had a woman and a man in their underwear; I guess they were showing it off. Madoka pointed at the screen and laughed. Others had music videos or numbers going across. Everything flashed and changed very quickly. We stood at the corner for a while, mesmerized by the displays. After we were able to tear our eyes away from them, we walked up and down Broadway for hours, staring at the store windows. I didn’t feel cold, as the number of people, the glittering buildings, and the sounds of cars overwhelmed and intrigued me. I thought I was dreaming. When we returned to the hotel later that night, we told the other children about what we had seen. After that, we all went out to Times Square every evening.

Madoka and I had wandered off to a few places in the city before our scheduled sightseeing days. We had been to Rockefeller Plaza, where we saw a huge decorated Christmas tree, statues of angels, and the people ice-skating. They kept going around and around, and Madoka and I couldn’t understand why they enjoyed this. We had also gone to the World Trade Center with Mr. Wright, a Canadian man we had met at the hotel. One evening, when the fifty-seven of us got on the subway on our way to the South Street Seaport, I asked Madoka, “How come everyone is so quiet?” He looked around the train and replied, “It is not the same as public transportation back home.” Shantha, the cameraperson for the event, who later became my aunt when I returned to live in New York, pointed the camera at us, and Madoka and I posed for her. On every trip I would make mental notes on things I needed to tell my uncle, cousins, and Mohamed. I didn’t think they would believe any of it.

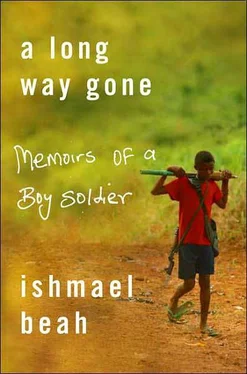

On the last day of the conference, a child from each country spoke briefly at the UN Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) chamber about their country and experiences. There were diplomats and all sorts of influential people. They wore suits and ties and sat upright listening to us. I proudly sat behind the Sierra Leone name plaque, listening and waiting for my turn to speak. I had a speech that had been written for me in Freetown, but I decided to speak from my heart, instead. I talked briefly about my experience and my hope that the war would end—it was the only way that adults would stop recruiting children. I began by saying, “I am from Sierra Leone, and the problem that is affecting us children is the war that forces us to run away from our homes, lose our families, and aimlessly roam the forests. As a result, we get involved in the conflict as soldiers, carriers of loads, and in many other difficult tasks. All this is because of starvation, the loss of our families, and the need to feel safe and be part of something when all else has broken down. I joined the army really because of the loss of my family and starvation. I wanted to avenge the deaths of my family. I also had to get some food to survive, and the only way to do that was to be part of the army. It was not easy being a soldier, but we just had to do it. I have been rehabilitated now, so don’t be afraid of me. I am not a soldier anymore; I am a child. We are all brothers and sisters. What I have learned from my experiences is that revenge is not good. I joined the army to avenge the deaths of my family and to survive, but I’ve come to learn that if I am going to take revenge, in that process I will kill another person whose family will want revenge; then revenge and revenge and revenge will never come to an end…”

Читать дальше