I spent ages trying to work out how to take a load of interviews and make a story out of it. I am very grateful to Rowland White, author of Vulcan , who allowed me to grill him for an afternoon on the technical side of writing. I also had to work out how to organise telling my own first-person story alongside the third-person stories of my colleagues. What I hope I have produced is a book with the personal feel of what it was like to be a young Royal Navy junglie pilot at war.

Without a war diary to work with, and with very fallible memories of events nearly thirty years ago, I’ve had to assemble a jigsaw puzzle of individual stories and reconcile them with the available records. Oddly, the least useful have been the official squadron records, only some of which were available, but which provided only the barest outline of events. Perhaps this was because they were written by squadron junior officers like me. I am grateful to Anna Clark at the Fleet Air Arm Museum, Yeovilton, for providing me with a great starting point. More accurate and interesting were the few official reports of proceedings submitted by commanding officers. These gave a good flavour and some fascinating details. Thank you especially to Mike Booth for lending me his report of Wessex squadron activities and to Bill Pollock for his report of the incredible Sea King night-flying missions. And to those who dusted off their old action photos for the book, especially Arthur Balls, Mark Brickell, Stewart Cooper, Rick Jolly, Pete Manley, Jerry Spence, Tim Stanning and Simon Thornewill.

Pilots’ log books were generally a very accurate source for dating particular sorties. Yet even these had inconsistencies. Two pilots flew their first sortie together in the Falklands but recorded it on different days. Another pilot managed to record the wrong airframe number for much of the war. By far the best written record is the extraordinary book The Falklands Air War by Rodney Burden et al (1986). It is dripping with details of the squadrons and individual aircraft on both sides. Without this resource I would have found it much harder to put together a timeline of events. By comparing this secondary source, official records and log books, I have been able to turn forty-five interviews and literally hundreds of vignettes into the story of the helicopter war in the Falklands.

I’ve also drawn from the following excellent works: Max Hastings and Simon Jenkins’s still fresh and gripping Battle for the Falklands; Richard Hutchings’s highly recommended personal account of the 846 Squadron night-flyers Special Forces Pilot; Rick Jolly’s story of the Red and Green Life Machine ; Nick van der Bijl’s insightful view of the land campaign, Victory in the Falklands ; Max Arthur’s collection of heroic deeds, Above All Courage ; and Roger Perkins’s detailed account of Operation Paraquat: The Battle for South Georgia .

There are many more terrific junglie stories in John Beattie’s wonderful collection The View from a Junglie Cockpit , published by and available from the Fleet Air Arm Museum. All of the interviews, records, spreadsheets, timelines, aircraft and combat details used for this book are now preserved in the Fleet Air Arm Museum’s archives. If you visit the Museum – and you should – you will see half of the Wessex that I flew in the war (painted Zulu Mike on the side, it was coded X-Ray Lima in the Falklands). Pete Manley, Ric Fox and Dave Greet’s Wessex, Yankee Sierra, is still intact and gets wheeled out on display at the Museum from time to time. It was the second Wessex to arrive in the Falklands.

A few final but crucial thankyous: to my agent Annabel Merullo for finding me a publisher; to Trevor Dolby at Random House who thought it good enough and then covered it in post-it notes telling me how to do it better; to Kate Johnson who edited the manuscript; to Nicola Taplin for putting it all together and finally to my family, for putting up with my erratic moods. It’s been emotionally exhausting spending so much time with half of my brain stuck in 1982 revisiting my own and everybody else’s experiences. I hope you enjoy reading our stories.

Harry Benson, March 2012

On my way to the Falklands as a newly qualified Wessex pilot. Twenty-one-year-old ‘Acting’ Sub Lieutenant Harry Benson RN of the newly formed 847 Naval Air Squadron.

Half of my squadron sailed to the Falklands on the flat bottomed helicopter support ship RFA Engadine . The sea wasn’t always as calm as this, just south of Ascension Island. At a painfully slow twelve knots, it took us four weeks to get from Plymouth to San Carlos. We could have swum faster.

Bill Pollock’s ‘night flyers’ were one of the keys to the British success in the Falklands. A last minute acquisition of seven sets of night vision goggles allowed four specially-adapted Sea Kings of 846 Squadron to fly SAS and SBS patrols in and out of the islands at night completely undetected.

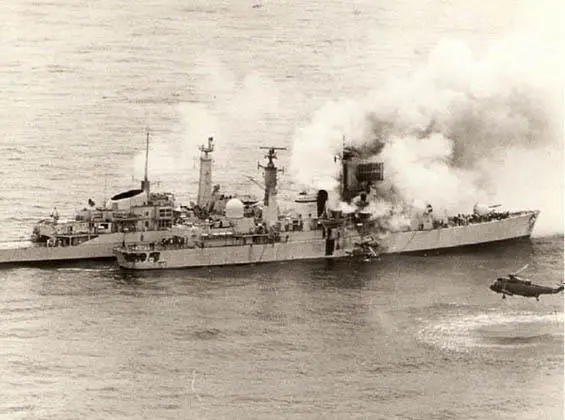

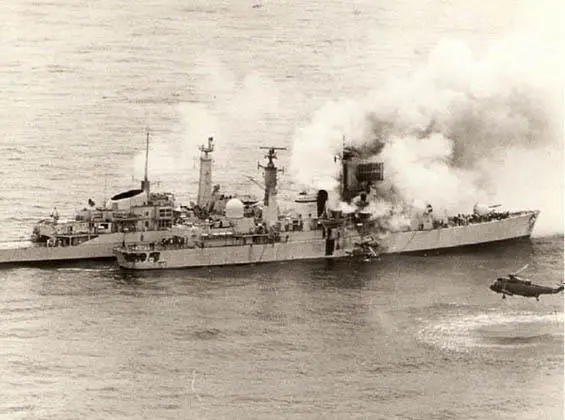

Until early May, few of us thought the Falklands war would actually take place. What changed was the sinking of two ships. For the Argentines, it was the torpedoing of the Belgrano . For the British, it was the Exocet strike on HMS Sheffield , seen here with HMS Arrow bravely alongside.

My colleagues in Yankee Charlie were the only Wessex crew to take part in the D-Day landings. Their first task was to collect a paratrooper who had damaged his back. But within hours, they had attended to two shot-down helicopters, watched most of the air attacks by the Argentine air force, been strafed by a Mirage and finished their day with a dramatic rescue of two sailors from the icy sea next to the burning HMS Ardent .

On the day of the San Carlos landings, Simon Thornewill and his seven ‘day’ Sea Kings of 846 Squadron disembarked over 900,000 pounds of stores and equipment and over 500 men. These two Sea Kings are operating from the rear of the two specially built flight decks on the liner SS Canberra .

Weather was always going to be a crucial factor in the D-Day landings at San Carlos. The morning started really well with overcast skies. But the clouds quickly burnt off, giving the Argentine jets a clear run at the British ships. Amazingly, throughout the war, not one British ship was successfully attacked within San Carlos water.

Even with the arrival of Atlantic Causeway and thirty more helicopters, helicopter lift was in short supply. Here a newly arrived Sea King of 825 Squadron lifts an underslung load while the troops of 5 Brigade have to walk.

The two amphibious assault ships HMS Fearless and Intrepid were the focus of both the San Carlos landings by 3 Brigade and the move forward to Fitzroy by 5 Brigade. This shows the stern being flooded to allow landing craft in and out. A Sea King of 825 Squadron is refuelling on the rear of the two landing spots.

One of the iconic shots of the Falklands war. Pete Manley and Ric Fox fly Wessex Yankee Sierra over the broken back of HMS Antelope in San Carlos water.

This was the astonishing sight confronting Oily Knight and Arthur Balls in their Wessex on the afternoon of 25 May. The helicopters hovering over the upturned HMS Coventry are all 846 Squadron junglie Sea Kings.

My 847 Squadron colleagues Tim Hughes and Bill Tuttey were first on the scene after the dreadful attack on RFA Sir Galahad and Sir Tristram at Port Pleasant. The identity of the SAS soldier kneeling in the doorway remains a mystery. After helping them throughout the rescue, he simply vanished.

Another of the iconic shots of the Falklands war. Hugh Clark’s 825 Squadron Sea King hovering in and out of the smoke from Sir Galahad while trying to blow the life rafts away from the ship.

Former Wessex boss Tim Stanning was in the back of Hugh Clark’s Sea King that was hovering in and out of the smoke from the burning Sir Galahad . This was his view from the aircraft cabin.

On 8 June, HMS Plymouth took the brunt of an attack by five Mirage jets in Falkland Sound. Amazingly none of the bombs went off. This is Paul McIntosh winching Rick Jolly and a stretcher onboard to help with the wounded.

The Forward Operating Base at Port San Carlos got a bit crowded after the reinforcement helicopters disembarked from Atlantic Causeway on 1 June. So the dozen Pinger Sea Kings moved around the corner to a new base at San Carlos the next day, leaving behind nineteen Wessex and the Chinook.

As the war ended, the weather became our new enemy. Al Doughty and I were half way across San Carlos water with an underslung load. We had just enough time to turn back and land before being hit by a sudden massive snowstorm. Seconds later, one of the engines flamed out under the sudden deluge of snow.

I may have been a highly trained and highly capable young pilot. But I nearly blew it the time I pushed down on the tail of a Pucara with a collapsed nose wheel at Goose Green just after the war. When I moved sideways to release, the Pucara’s tail flipped violently back up, narrowly missing the explosive flotation canister on the Wessex wheel.

Every squadron likes its formation fly pasts. These are some of our 847 Squadron Wessex celebrating the move from Port San Carlos to snow-covered Navy Point, opposite Port Stanley, a few days after the war. Stanley airfield is in the distance behind the helicopters.

Having arrived late for the war, 847 Squadron was probably the last active service unit to leave the Falkland Islands. We flew back in dribs and drabs first to Ascension by Hercules and then on to Brize Norton by VC10. I was very relieved to be back after four and a half months away. There was no official welcome for us. But my mum was happy.

Two years after the Falklands war, I’m in warmer climes as Lieutenant Benson RN, Wasp pilot and flight commander of HMS Apollo .

Читать дальше