Night formation is simple in theory. On the tips of the rotor blades and along the spine of the Wessex are about a dozen beta lights. These give off a faint green glow in the dark. The effect is to produce a disk of light from the spinning rotors. The pilot flying in echelon judges his position using the shape of the disk and the angle of the lights on the spine of the lead aircraft. He judges his distance by the extent to which he can see the red lights of the lead aircraft cockpit. If he can barely see the cockpit lights, he’s too far away. If he can actually read the instruments, he’s about to collide. It’s quite an adventure.

The first problem is that flying smoothly enough to stay in stable close formation is hard enough during daylight, let alone in the pitch black. Fear and uncertainty lead to inevitable overcontrolling and wild swings in aircraft positioning. The second problem is how on earth to join up after launching from a ship where a formation take-off is impossible. As the more experienced pilot, Tidd put Berryman in the pilot’s right-hand seat. This meant that Tidd’s head was squashed in behind the M260 missile sight in the aimer’s left seat. After ‘frightening themselves fartless’ trying to join up with the other Wessex, the idea of a tactical night insert was quietly and sensibly binned.

Although Tidd, Pulford and Georgeson all had experience of Arctic mountain flying in northern Norway, any notion that South Georgia would be a similar environment was quickly disabused following an extensive briefing from Lieutenant Commander Tony Ellerbeck, Wasp flight commander from Endurance . His description of the Antarctic weather sounded pretty unpleasant. None of them fully realised quite how unpredictable and violent it would turn out to be. As for the SAS plan, Ellerbeck was not impressed. ‘They are out of their tiny trees,’ he told Antrim ’s Ian Stanley.

Nevertheless, against the advice of all those with local experience of the severe conditions, the SAS mission went ahead. On the morning of Wednesday 21 April, with Antrim positioned some fifteen miles off the coast of South Georgia, Ian Stanley and his crew took off in their anti-submarine Wessex 3 from Antrim to attempt a recce of Fortuna Glacier.

For the first time, Stanley began to grasp the sheer scale of the task. The scenery was awe-inspiring, breathtaking. Gigantic black granite cliffs rose 2,000 feet vertically out of the sea. Fragmented shoulders of ice spilled off the edge of glaciers. The wind whipping around the bays produced considerable turbulence even before they got into the mountains. An engine failure in these freezing waters would be bad enough. The thought of climbing up into the mountains in these hostile conditions, even with a working engine, was not remotely appealing.

Stanley returned to Antrim to load the few troops he could take into his cramped cabin. He cleared the deck to make way for Yankee Foxtrot, flown by Mike Tidd, and Yankee Alpha, flown by Andy Pulford, to load up their aircraft one at a time with the bulk of the troops. The three aircraft formation then set off across Cape Constance and into Antarctic Bay towards the foot of Fortuna Glacier. However, a heavy snowstorm made further progress impossible and the formation returned to Antrim .

With the weather changing rapidly and violently, Stanley returned for a further recce with the SAS mission commander Cedric Delves and team leader John Hamilton. This time conditions had cleared sufficiently for them to hover-taxi at low level up the face of the glacier. As they climbed, co-pilot Stewart Cooper was mesmerised as the radio altimeter flickered from 30 feet to 200 feet and back almost immediately. The aircraft was crossing deep blue crevasses that cracked the white icy surface of the glacier. At the top of Fortuna, it was clear that Hamilton was less than thrilled at the prospect of legging it over the top of the mountains. Ian Stanley chuckled wryly as he heard Delves tell him: ‘You’ve got to get on John.’

Back one more time to Antrim , the formation loaded up, delayed yet again by a heavy snow shower. This time all three Wessex managed to work their way back up the glacier, buffeted violently in the heavy turbulence and snow squalls. One moment an aircraft would be in full autorotation with no power applied and yet still climbing. Another, they would have full power applied and still be going down. On each occasion, the pilots had to trust that the updraft or downdraft would reverse direction before too long.

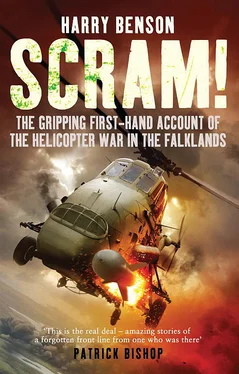

This is one of the two ill-fated Wessex 5s on their way to drop SAS troops on the top of Fortuna Glacier in South Georgia. The massive cliffs give a hint of the awesome scale and power that lay ahead of them up in the mountains.

Stanley’s first attempt to put his wheels down on the glacier was nearly disastrous. Only a warning from the crewman, Fitzgerald, and quick reactions from Stanley prevented the Wessex 3 from slipping into a crevasse. Behind him, Tidd was unable to bring his aircraft to a hover at all and was forced to circle round again. Pulford managed to land using the lead aircraft as a reference point. His crewman, Jan Lomas, voiced what all the other aircrew were thinking: ‘What a bloody stupid idea this is.’

Visibility shifted from clear to zero to clear with alarming speed. Still flying their aircraft on the icy surface with the wind gusting sixty knots, the pilots watched the SAS troops unload their equipment. All three aircraft were now profoundly unstable as the Wessex airframes shook from side to side.

Tidd was first to clear out his passengers, commenting to Tug Wilson in the back: ‘What on earth are these prats coming up here for. They’ll be lucky not to fall into one these crevasses.’ Eager to get off the treacherous mountain, Tidd decided to lift off early in order to take advantage of a clear gap in the weather that had suddenly opened up in front of him. It was a precursor to his fateful decision the following day. After receiving a thumbs-up from the SAS troop commander Hamilton, the two other Wessex gladly lifted off and headed down the glacier to join Tidd for the trip back to Antrim and Tidespring out at sea. ‘Thank God we’ll never have to do that again,’ announced a relieved Tidd on arrival back on board, prematurely as it turned out.

That night was a shocker. The weather worsened dramatically. The barometer dropped thirty millibars within an hour; the wind gusted to over 100 knots, and the seas became huge and burst over the bow of the rolling ships. On the flight decks of both Antrim and Tidespring , a Wessex remained open to the appalling weather, partly because of the danger of moving the aircraft into their respective hangars, partly to keep aircraft available on alert. On Tidespring , the Wessex maintenance crew were forced to lash heavy manila ropes to stop the blades thrashing themselves to death. The normal tipsocks were simply inadequate for the task. On Antrim , wardroom film night was abandoned as the projector became too hard to hold down. On Fortuna Glacier, the SAS troops had only moved a few hundred yards and were vainly digging themselves into the ice to gain even a few inches of shelter from the driving wind and snow.

It was no surprise the following morning, Thursday 22 April, when the signal came through from Hamilton requesting emergency evacuation. His team were suffering from frostbite and exposure. Tidd’s roster put Ian Georgeson and Andy Berryman in the frame to fly the two Wessex 5s. But whereas he was happy for Arctic-trained Georgeson to fly in these appalling conditions, he was less willing to let the less experienced Berryman go, despite the fact that Berryman was an extremely competent young pilot. ‘It’s not a “first tourist” day,’ said Tidd.

Читать дальше