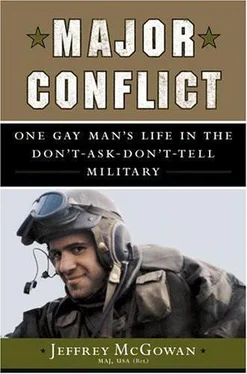

Jeffrey McGowan

MAJOR CONFLICT

One Man’s Life in the Don’t-Ask-Don’t-Tell Military

To my grandparents, who loved me unconditionally and who will always be my heroes, and to the men and women who serve in silence, your sacrifice and perseverance will be recognized soon.

Whenever I used to pick up a book, I would thumb past the acknowledgments so I could dive right into the first chapter. Now, of course, I realize that no book is written truly alone and I will always stop to find out about the people who made a difference for the author. I could probably write a book recognizing the many contributions of the people that I cite below. However, even though space is limited, I wish to dwell a moment on several very important people without whom my efforts would never have come to fruition.

I want to begin with my agent, Ian Kleinert, who is a consummate professional and a genuinely good person, whom I respect greatly. Ian has been there for me every step of the way, looking out for my best interests. He is probably the most patient person I know, having taken countless phone calls from me, as he guided me through the entire process. His agency has the feel of a large family that really cares about the people they represent. I am truly lucky to be associated with such a wonderful group. A special note of thanks to Kathy Barboza who was always helpful and kind over the phone, a company couldn’t have a better person to greet its clients when they call.

I wish to thank my editor, Stacy Creamer, for believing in me and giving me the opportunity to tell my story. She is a great listener and a warm person who was easy to work with. Her insight taught me many things about writing and I admire her greatly for her keen intellect and sophistication. I also wish to recognize her assistant, Tracy Zupancis, whose diligence and thoroughness will make her an editor in chief one day. Her kind, gentle manner always brightened my day whenever we spoke.

Of course, how could I not take a moment to recognize the men in my life, Greg, Paul, and Billy. To Greg Torso, thank you for being there for me. Your recollections and insight, not to mention your journals, gave me the added perspective that allowed me to look at my life more deeply, resulting in a more nuanced book. Thank you for helping me with your opinions and revisions. Special thanks to Chelsea and Dave for letting me use your home and for your insightful feedback. To Paul, thank you for understanding. To Billy, I love you, I want to spend the rest of my life with you. To my mother, I love you.

To my friends, Willy, Jeffrey, Charles and Maurice, Andrea and Claudio, Carla and Michael, Michael Littler, Sari, Julia, Jason West, John Shields, Erna Berger, Dr. Duggan, Christine Karam, Emily Kerr, Steven and Denise, Tara, Larry Cavazza, Cindy Delgado, and Judy Mayle, you guys are simply the best.

To my beloved and much missed friend Vincent, you inspired me to be more than I could be on my own, I miss you deeply and will love you always. To Jed, his partner, your loyalty, love, generosity and kindness make you a true hero and I am honored to call you my friend.

To my boss, Jim Stephens, thanks for being a great leader and busting my balls relentlessly to be the best salesman I could be. To my district, Amy, James, Tom, Paul, Pete, Ted, Tom, and Chris, There isn’t a better bunch to work with anywhere.

To my comrades in arms, in particular Duncan Barry and his lovely wife, Tonianne, Paul Mapp, Brian Hathaway, and Mike Poling, thank you for being heroes and patriots, I love and respect you guys because you made me a better person.

Finally, if I missed anyone, thank you for being there for me.

JULY 22, 1991. SAUDI ARABIA

The ancient yellow school bus was obviously not built for comfort. And it certainly wasn’t built to travel over the sun-baked roads of Jubail, Saudi Arabia. The road was lined with crevices and holes, and as the old bus rolled into one and then the other, it felt as if my kidneys were being dislodged and my lunch would soon be out the window. Add the heat—a relentless, blinding, 110 degrees—and it’s not a great leap to say that we were living and working in a place not unlike hell. The view through the dust-caked windows often confirmed our suspicion that we’d been dropped to that lower place. Toothless men wearing torn and shabby robes stood by squat, sun-bleached buildings made of concrete block, eyeing us with suspicion and hate. It wasn’t hard to imagine one of these men, rushing toward the old yellow bus, a bandolier of C-1 or dynamite strapped around his waist, in order to take out the Western infidels. I knew I wouldn’t feel safe until we were wheels-up in the transport plane.

This tour of duty had been an especially hard one. Six long months of MREs (meals ready to eat, also called Mires) and sleepless nights spent on uncomfortable cots. But it was all good now. Now that we were leaving the kingdom, it was all just sandy water under the bridge. We were on our way back to civilization, back to Europe—to Sitting on the plane, I couldn’t help but think how much the axis of the world had changed in just one short year. Prior to this mission into Saddam’s hell, we were still in full Soviet mode, covertly moving along the East German borders, working up battle plans in the event of a thermonuclear war. We were busying ourselves with the day-today tasks of war without actually firing a shot. Staring out the window on my way back to Germany, I couldn’t help thinking, God love the gentlemanly tones of the cold war! But all that had come to a thunderous halt when one egomaniacal tyrant decided to tinker with the geography of the Arabian Peninsula. Saddam Hussein embarked on a gamble that he’d eventually lose, and lose big, leaving his elite Republican Guard with fifty thousand fewer men.

Before the war actually began we all thought it was going to be a toe-to-toe heavy-metal battle. We had acquired much recon and been briefed on the fighting capabilities of the Republican Guard, which, with over more than five hundred thousand troops, was the fourth-largest army in the world. We knew our mission, and we were going to have to hit them with the force of a jackhammer. Plain and simple: that was our job. Our task was clear, and there was no room for error.

Of course we had great confidence in our own capabilities. We were the best-trained army on the planet, and we were able to maintain a high level of readiness on every terrain imaginable. What we didn’t realize, though, was just how easy it would be, how one-sided the victory would end up being.

Technically it was a three-day war, supremely executed by all the armed forces of the United States. When it was over, we pretty much owned Kuwait and had to remain there to keep the peace until the oil-rich country was back to normal and reestablished as a free and sovereign nation.

I served as a lieutenant in Operation Desert Storm and Desert Shield. For six months I served proudly and without question in these campaigns and as a result was awarded a bronze star and various campaign medals. The unit I was in received a valorous unit citation. I think I was most proud of this since, as their leader, it felt as if my own sons were being honored. After the war I felt as if I was on top of the world. Finally, I was truly where I wanted to be: a leader, an officer, a gentleman, a soldier. Still, something was missing. Sitting on that plane heading back to Germany, I knew that in order to achieve my goals I’d made a great sacrifice, namely a big chunk of myself, and I was beginning to wonder how long I could continue being just half a person.

Читать дальше