His brother Alvan was two years older. Alvan called to his brother, loitering as usual, in the darkness. There was a new call from Lincoln. Alvan said, “I’m going.”

Charles went with him.

The younger of the two boys came back. He had no words with which to tell his mother of those last scenes, when she asked him. He had never laughed much. Now he tried to laugh it off, a raw imitation of Alvan’s contagious laughter.

Alvan was dead. He hadn’t been shot through with a bullet. They were rotting. . they were. . it was typhoid. “It was quick,” he told his mother. He tried to remember something from Lincoln’s last speech, he could only remember “a great battlefield of this war,” but it wasn’t a battlefield of war, not of this war. . he knew that his mother felt now that a million free emancipated darkies weren’t worth Alvan. Or didn’t she? It was better not to know what she was thinking. He knew his mother was trying to love him, he had made that effort to come back to tell her. . what he never told her.

He hadn’t got a single reb, he told his father. Celia wished he wouldn’t laugh in that way, so unlike Alvan, she felt he would choke. The elder Charles felt something of it. He asked Celia to fetch the Bible. “Sweeter than honey in the honeycomb,” he read, opening it anywhere. Celia wished the boy wouldn’t stare so. How could he tell his mother of the makeshift camp-hospital. . at the end, there wasn’t anyone left. . He crawled through some trees. He remembered juniper, birch, balm, and hickory. He muttered these clean words under his breath like a prayer. Alvan was dead. He must get back home somehow, to tell them. . “The rebs left just as we got there, the camp —” His father went on reading, “Yea, than much fine gold.”

He was shaken with the after-effects of the malaria and could scarcely stand up. Every time his eyes met Celia’s he saw Alvan. He knew Celia saw Alvan too. Why had he come back? Why did we ever come west, thought Celia. That knocking? It was some friendly neighbor, they were all too friendly. She almost dropped the pan of corncake; it was the thud-thud of a hoe or maybe that colt loose again from the meadow. It might even be the kitchen clock; its tick was so loud she never noticed the clock back home. Slow now, if you stopped to listen. Time was so slow now. She could scream when she saw, through the open window, Charles sprawled out on the porch steps. He couldn’t yet drag his shambling length after the plow.

He had taken his grandfather’s old bubble-watch and laid it on the floorboards. What was he doing, chalking a clock-face round the bubble-watch? A stick was dangling from a string. It was fastened to the hook in the ceiling where Mercy had had her swing. Rosa was off, upstate to learn to be a teacher. Mercy was dead. There was no one here to help her. What was he doing marking along the shadow where the sun fell, with that chalk? Had he gone mad?

How old was Charles now? He was seventeen when he went with Alvan and lied about it, so they took him. Mercy and he had paired off together. Alvan and Rosa. She remembered how she had had to reprove Mercy for sing-songing, when it came her turn for reading.

The Bible was for decorum.

March 22, Wednesday, 6:30 P.M.

I gave the Professor Bryher’s books. He seemed rather professional and aloof after using half my session yesterday in gossip. I tell him last night’s dream: hotel, stranger, dark (or in-the-dark) young man in the hall, he passes the open door and sees me. I wear a rose-colored picture-gown or ball-gown. I am pleased that he sees me and pose or sway as if forward to a dance. In a moment, he has caught me, I am lost (found?), we sway together like butterflies. He says, “You do know how to dance.”

Now we go out together but I am in evening-dress, that is, I wear clothes like his. (I had been looking at some new pictures of Marlene Dietrich, in one of the café picture-papers.) I am not quite comfortable, not quite myself, my trouser-band does not fit very well; I realize that I have on, underneath the trousers, my ordinary underclothes, or rather I was wearing the long party-slip that apparently belonged to the ballgown. The dream ends on a note of frustration and bewilderment.

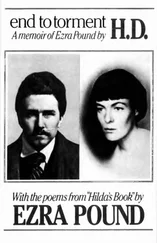

This dream seems to have some association with Ezra; though he danced so badly, I did go to school-girl dances with him. The Professor knew the name, Ezra Pound. He said he had seen an article, but could not pretend to follow it. I told the Professor how Ezra had been more or less “forbidden the house,” and the conflict at that time with my parents.

8:20 P.M.

I feel old. When I told the Professor of a much younger admirer of mine who had flattered and mildly “courted” me, the Professor said, “Was that only two years ago,” as if at my age (forty-six) I should be well over that sort of trifling. But I remembered the novel Wagadoo that Dr. Sachs brought us to read. As I remember, the woman in the book began her analysis at forty-seven. . and she was at that age deeply involved in various love experiences or experiments. But that was French. Vienna, too, develops differently. The Professor seemed to be surprised when I told him that my first serious love-conflict or encounter was with Ezra when I was nineteen; he said then, “As late as nineteen?” Perhaps, this is some technical mannerism or façon de parler.

Ezra and I took long walks; I remember the hepaticas, the spring is late in America, at least compared with England. I was triumphant if I found my first cluster of blue flowers or a frail stalk of wood anemone or bloodroot, the last day or one of the last days of March. To find flowers in March was a great triumph for us there.

I had not time to speak of my dream of the two Japanese-like dwarfs. Their surname is Anemone. (Japanese anemones. . Bryher brought them to me several times a week at St. Faith’s Nursing Home before my child was born; they are associated particularly with that time.) I discuss the dwarfs with my mother and we are both annoyed that they should have that flower-name.

March 23, 8:45 P.M.

I started to hold forth on Frazer and The Golden Bough. The Professor waved me to the couch, “More confession?” I said, no, I wanted to go over some of the old ground again. “I will go back to Van Eck, do you remember Van Eck?” He said, “Of course.” I told him that I felt reticent and shy coming back to all this. I told him of the crystal arriving in the State Express Cigarette box and a letter that I received, sent by Van Eck from Alexandria. I was then at Mullion Cove, Cornwall, with Bryher. The box had come to the new furnished flat we had found at Buckingham Mansions, Kensington, the preceding summer. It was the summer before this, July 1919, that we had gone first to the Scilly Isles together. The crystal seemed to carry out my vision or state of transcendental imagination when I had felt myself surrounded, as it were, with the two halves of the bell-jar.

I told the Professor how after some years I had met the cousin of Van Eck, or rather her sister, to whom he had written a letter, enclosed in this Mullion Cove note to me. I presented the letter, or sent it rather with a small book of my poems, but Miss Van Eck never answered. Then, I met her sister in the Hotel Washington, Curzon Street, where I stayed when I went over to London.

I was now under the impression that Van Eck had been a total illusion or figment of my imagination, but when I mentioned him, and his helping Bryher on the boat with her Greek, to the younger Miss Van Eck, she said, “Yes, he always was very good at languages.” So, there actually was a Van Eck and this lady and the elder, whom I had not met, were in fact his cousins.

Читать дальше