The indeterminate and indefinable, elemental to fiction, complicate any naming. Inexorably, all writing fits into genres, like the genre-bending novel, which has itself become a genre. Wishing for scientific and technological discoveries or an avant garde to save and advance society and culture is futile; it supports, in the sense Modernism did, the idea of more advanced and superior articulations in writing, of a loftier civilization, less bellicose, more civilized, and an expanded human consciousness — progress. But the machinations and machines of the 20th century should have eviscerated this understandable illusion, since, by midcentury, progress ate its babies alive. So, no progress in literature or art, only differences and changes, contemporary responses and aesthetic variations: Mrs. Dalloway is not better than Middlemarch , Zeno’s Conscience isn’t better than Augustine’s Confessions . And the other way around.

If the reader accepts, as I do, that no object has inherent value, that it is re-made by passing generations of readers and viewers — the erratic history of the worth and reputation of authors’ work attests to this — no form can be privileged, no judgment eternal. Consciousness, in all its manifestations, will come to be represented variously by each generation for their different days and nights; since what is around people, what we see, hear, watch, exist in, affects our being and becoming, our reactions and what we make, as our psychologies shift within parameters of basic needs, new hungers and expanded wants.

Human beings are fantastic and horrifyingly adaptive creatures, fashioning tools or re-tooling, making nice, making war, building up and tearing down. Things change, they stay the same, the world changes and doesn’t, simultaneously. Writers rue rewriting old narratives, despair that there’s nothing new under the sun, except, say, a depleted ozone level, which will engender a plethora of apocalyptic myths. Still, an object can be shaken up and turned on its head, a word set beside another can create a shattering collision, like John Milton’s use of “gray” as an adjective in his poem, “Lycidas.” Still, fiction will thrive primarily through readers’ imaginative capacities, which means that how and what we read is ultimately more crucial than how and what we write.

Those of us who are practicioners live in interesting times. Writing now is like doing laps without a pool. Maybe we wail in an aesthetic void or shout in a black hole, life’s empty or dense; we can’t know what we’re in — fish probably don’t know they’re in water (who can be certain, though). But uncertainty is not the same as ignorance, it may point writers toward other registers of meaning, other articulations. Complacency is writing’s most determined enemy, and we writers, and readers, have been handed an ambivalent gift: Doubt. It robs us of assurance, while it raises possibility.

Fiction is the enemy of facts, facts are not the same as truths. Fiction is inimical to goals, resistant to didacticism, its moralities question morality, its mind changes, while explanations crash and burn, mocking explicability. Fiction also claims that seeming lies can be true, because everything we say and don’t say, know and don’t know, tells and reveals. Novels and stories are not training manuals, their “information” is gleaned by readers in their terms and for their own uses, often not easily comprehended in part or whole, or never. Knowing the plot of Oedipus Rex , say, doesn’t change its powerful effects, for its enunciation of the unspeakable, the way it’s written and its evocation of the mystery and tragedy of human desire overwhelm any one of its parts. A great story is necessarily greater than its plot.

Call these statements a polemic or rant or a partial theoretical background to my own writing, my catholic or promiscuous inclinations. I’m for generative types of contemporary writing, not for proscriptions about writing. I don’t have a secure or immovable position, my various notions on writing might include contradictions, I’m sure they do. I don’t want to take A Position. Not taking a position is a position that acknowledges the inability to know with absolute surety, that says: Writing is like life, there are many ways of doing it, survival depends on flexibility. Anything can be on the page. What isn’t there now?

A Conversation with Peter Dreher

In 1994, I visited the Museum für Neue Kunst in Freiburg. My host, artist Dirk Gortler, showed me a thick, gray book with page after page of gray-toned reproductions — all paintings of the same water glass. Dirk told me Peter Dreher did the same painting every day — there are now over 2,500 of them — and taught in the art academy there. I bought the book, then asked Dirk to send me two more copies. Recently Dreher was in New York for his opening at the Monique Knowlton Gallery. I went and asked if I could interview him. We talked the next morning at the gallery. When I was leaving, he graciously said, “Even if nothing else happens, it was good to talk with you,” which turned out to be portentous. I walked up Broadway, rewound the tape, and started to play it back. There was nothing on it. “Even if nothing…” I phoned him, told him there was nothing on the tape, made another appointment for later that night — he was leaving New York in a day — and bought a new tape recorder. I was intent upon doing this, obsessed, in a way. There were some differences between the first and second interviews — it’s extremely difficult to have exactly the same conversation twice. I think we laughed more the second time.

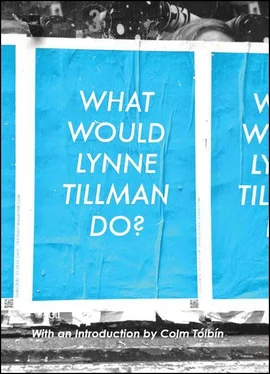

Lynne Tillman: You paint the same object every day. You have since 1974. That fascinates me.

Peter Dreher: Is this the question?

LT: Do whatever you want with it.

PD: It’s difficult to say the second time.

LT: You paint the same thing every day, this should be easy for you. In fact, if I had planned it.

PD: Did you plan it?

LT: No. But if I had, I’d have been more Machiavellian than I ever thought myself.

PD: Many ideas came together. When I was sitting in a bathtub — I love to sit in hot bathtubs, I have all my ideas there — I had the idea to paint the most simple thing I could imagine. Before that I painted large, gray paintings which showed a sort of optical illusion. I thought they were something very simple. But you could identify them as pieces of art only in a museum or gallery. Outside, in the streets, nobody would recognize them as art. I thought it should be more simple than just painting a wall white like Yves Klein did. And what is more simple than to take something usual, like a glass — I mean, something invisible — and place it on a white table before white walls, a white, white glass. Something you could see everywhere, everybody’s used it. It’s something like Hitchcock’s idea of hiding a diamond in a chandelier, which is more simple in the mind than in the form. That was one idea, and I thought the next step would be to do this simple thing, with its simple motive, again and again and again. I had the idea to paint it five or six times. I did one, two, three, then five, then seven, then 10, then 100. I couldn’t stop, and it became fascinating. I think the whole history of art — no, let’s say the history of the problems in painting — came to me in the last 22 years.

LT: As you were doing this.

PD: Yes.

LT: It’s interesting you mention Hitchcock. The viewer can see a little window in the glass. When you look closely at your paintings, you see minute details, minute changes. The window is made with just a few, tiny strokes of different colors. And you — the painter — are in the window. Hitchcock made Rear Window ; and in your paintings, the window’s at the rear of the glass. You said you wanted something that could be recognized as a piece of art not only in a gallery.

Читать дальше