Saunders avoids righteousness and pleading. He understands Mary McCarthy’s observation in “A Charmed Life,” “Nobody can have a permanent claim on being the injured party,” and his earnestness and seriousness propel him instead, as they did McCarthy, to satire and parody. Imagine Lewis’s Babbitt thrown into the back seat of a car going cross-country, driven by R. Crumb, Matt Groening, Lynda Barry, Harvey Pekar or Spike Jonze. That’d be a story Saunders could tell.

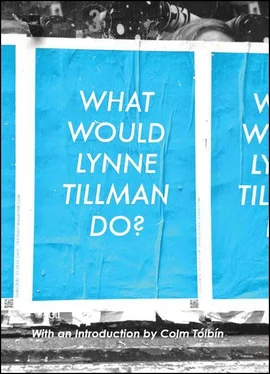

T is for What Would Lynne Tillman Do

I wrote a first novel. I spent years on it, and, when it came out, it was just a book. I had worried about its cover, but it was just a cover. When I went into a bookstore, I saw it was just a book among many others, or it wasn’t even there. Its dwarfed presence or absence made me think: Why add another book, I haven’t even read all the books here? Or, narcissistically: Why publish a book if even I can’t find it? When it was reviewed, the reviews were just words, often the wrong words. I spent months in bed, overwhelmed by my naïveté and folly. All my suppressed hopes acted like a tsunami and reduced me to nothing; my wishes were too big for any book, especially a first book. Later, I discovered it was the book that readers knew, if they knew any of mine, and no others. It was also the book whose existence made me realize that writing before publication was sweeter. Then I could think about my work the way I wanted: It didn’t exist for others, and nothing about it could be disputed, including its presence.

Write your first novel, put everything you know and don’t know into it, and stow it in the back of a drawer. Do this with your agent’s cooperation. Ask her or him to spread the word in the industry that your first novel is explosive, revealing, scandalous, so brilliantly written that you are the new Pynchon, Morrison, Austen, Beckett, Joyce, Woolf, Burroughs. You have created — no, invented — an entirely new novel, whose time has not yet come; it cannot be exposed to the public. Instead, the manuscript on offer is your second novel, which is even better, as it is more mature.

Your second novel is not roman à clef or a bildungsroman, not thinly disguised or outright autobiography. It is not based on your terrible past, whose egregious trials mock the reality of childhood innocence. The protagonist is not you. If the secondary characters appear to be you, they are cleverly achieved. The reader will not look for you, the author. You have skipped all the troubles of the first novel by presenting your second, first. Let others wonder about the first. Someday, you suggest, you may allow it to be published. But only after everyone, including you, has died.

Doing Laps without a Pool

In the beginning, there seems just one way to write, the way it comes out, and then that way becomes a debate, contested, most essentially, in and by its writer. Hopefully, a writer reads and reads and will become more conscious of decisions in style and form. Some writers make these choices more consciously than others, the decisions mark differences in fiction, though whether they might be experiments can’t be assumed, certainly not by their authors.

The term “experimental” and others that characterize or categorize writing have, for me, lost their explanatory power. Mainstream, conventional, innovative, progressive, whatever value they hold or once held, the notions are vague, and they lack agreed-upon meanings among writers, readers and critics. Rather than being descriptive, the characterizations are predictive and can mark expectation, both writers’ and readers’. Also, they are outmoded and unhelpful, even as heuristic tools; still, they survive, like the human appendix, without usefulness. Lacking other terms, we writers are their hapless recidivists.

If a writer has an idea about how writing should act, or what a reader should experience, it can occupy the writing, which then might foreground the writer’s beliefs and a priori aesthetic preoccupations, which then might preclude a sensation, for a reader, of its “newness” (even when writing is not technically “new,” as most isn’t). A writer’s discovering or discerning a way to write “it,” whatever that is, finding a style, structure, subject to realize “it” through his or her capacities and sensibilities, lies outside of proscription. It’s not that any of us can, with clairvoyance, recognize our ensnarement in and by language or in the grand, middling and small narratives that construct our lives, but it is a writer’s most essential work to be conscious of the act of writing, of enabling words to do as much as possible, for instance.

Our business is to see what we can do with the old English language as it is. How can we combine old words in new orders so that they create beauty and that they tell the truth. That is the question. [Words] hate anything that stamps them with one meaning or one attitude. What is our nature, but to change. It is because the truth they try to catch is many-sided, they convey it by being many-sided, dashing this way and that. Thus they mean one thing to one person, another thing to another person.

— Virginia Woolf, from “A Eulogy to Words,” BBC Radio broadcast 1938

Sometimes finding the best word, best way of saying it, at least to the writer’s mind, can be less accommodating to a reader; difficulty is always relative. But how a writer’s trials, errors and successes add, or not, to a body called literature draws consensus in one time that might be denied in another. Believing in how it should be written, a way to write, also bedevils reasons to write; for me, the necessity to figure out how to accomplish a story or novel pushes me on. Many writers talk about sensing necessity in fiction, feeling it in a story, in its writing, which does not imply subject, psychology, relevance or reason, since nonsense can have necessity in the way it’s written. Harry Mathews once remarked, and I paraphrase, It’s not what you write about, it’s how you write it. This is the ineffable which makes writing about writing so hard.

Unquestioned adherence to any dictates — about arcs, character development, fragmentation, dramatic tension, use of semicolons or adjectives, closure, character development or assassination, resolution or anti-closure — to any MFA workshop credos, or their antitheses, for a novel, story, poem, essay, will generate competent, often unexciting work, whether called mainstream, conventional, progressive or experimental; these products will have been influenced by or derived from, almost invariably and without exception, “established” or earlier work, their predecessors. In writing, “derivativeness,” except in extreme cases, is a cagey issue, since all things flow from others; discontinuities emerge from a writer’s objections, conscious and unconscious, to earlier literary approaches. But contemporary art and writing can be thoughtless or mindful re-inventions, dull or highly creative imitations, resonant and generative reworkings; new work can also glide, skip or jump off of culture’s secure bases and revamp them remarkably, keeping the racquet, just restringing it. It’s assumed there’s less conformity in “experimental fiction.” But what constitutes a genuine experiment in an “experimental” text? An argument might go: A true paradigm shift will model what follows, and these accumulate and accrete to the next. So, a convention results from earlier breaks or reformulations — Gertrude Stein’s, Jane Bowles’, Henry James’ with the novel — and, augmented over time and by practice, the “experimental novel” becomes recognizable, no longer really an experiment but in the spirit or school of such. “Innovative” is used instead of “experimental,” and that’s often allied with “fresh,” “edgy,” “inventive,” “novel,” “groundbreaking.” Then there’s “unique,” but how many formulations can be? The “literary novel”—what is it? Uncommercial? Conventionally experimental? And, how is “literariness” measured? And then there’s “progressive.” What is progressive writing, is it in its subject matter, politics or style? Or all three? Can there be a measure for it, whatever it might be, in its own time or before readers experience it?

Читать дальше