But by all outward appearances, Stewart seemed pretty relaxed. “For me, a talk show was never really the goal,” he said. “People that worry about where they’re going next generally don’t end up where they think they’re going. I just worry about what I’m doing now and try to make it good. When you’ve got too much of a master plan, it’s going to fail.”

* * *

Once Stewart had settled into his job and the staffers became comfortable with their new direction, it was time to hire a couple of new correspondents since Brown and Unger, who’d left when Kilborn departed, hadn’t been immediately replaced. Producers wanted to be sure to match any new correspondents with the new direction of the show. They asked around the studio for suggestions, and Colbert suggested Steve Carell, who he’d worked with at Second City and on The Dana Carvey Show .

In the meantime, Stewart had begun to transform the job of fake anchor—which Craig Kilborn had always delivered with a healthy dose of smugness—into something uniquely his own. Instead of conveying fake headlines with a huge wink to the audience as Kilborn had done, Stewart’s tone took on more of an inclusive air, more of a sense of being in on the joke, as if he were saying, “Can you believe these guys?”

Even though the show was now The Daily Show with Jon Stewart , whereas Craig Kilborn’s name hadn’t appeared anywhere in the show’s title, one thing that viewers found refreshing about the show was that even though Stewart set the tone of the show, it wasn’t about him, but about his ability to share the absurdity of current events with an audience of people who could definitely appreciate it. “Jon Stewart has brought back a kind of an everyman intellectualism,” said Brian Farnham, then editor-in-chief of Time Out New York. “He was that smart guy you knew in college [who] was funny and saying the thing that you were thinking and wish[ing] you could say.”

Stewart concurred.

The show was a natural fit for him, he was enjoying himself despite the breakneck schedule of cranking out four shows each week, and the job clearly was not going to go away anytime soon. As a result, Jon appeared to, well, become more Jon . “I always liked him, but when he became Jon Stewart he seemed to become more content with who he was,” said Noam Dworman, who owned the Comedy Cellar where Stewart had cut his teeth in stand-up. “He seemed to be where he was and felt he should be, and it seemed to have a relaxing effect on his personality.”

Even though he became more Jon on The Daily Show, Stewart said that just like his stand-up persona was a more exaggerated version of himself, the same applied to his TV host persona.

“It’s pretty close, but also not close in the sense of I don’t live my life like it’s a half hour, like it’s a show, it’s a performance,” he said. “At home, I don’t go to commercial after breakfast. I’m not playing a character, it’s just a heightened performance.”

He did admit that after years of starts and stops, The Daily Show was where he hit on all cylinders. “The only things that I am able to do, I am able to do here,” he said.

For maybe the first time in his life, he was being true to himself.

“I think people are responsible for themselves, for the most part,” he added. “I think you’re responsible to present yourself, to be as positive a person as you can be, whether it’s because you’re Jewish or black or Asian or whatever you are. I honestly think we’d be so much better off if that’s what people focus on. There’s really one rule: the golden rule. Focus on that, and it really doesn’t matter.”

Lest some people think he was solely on the lookout for a news hook or story to turn into a joke, the daily headlines of that first year on the air were not all fair game for Stewart and the team. “All of the images coming out of Kosovo were so horrific, you think,… ‘There’s nothing funny about this,’” he said. “And then… ‘Fabio got hit in the face with a goose!’… It was like receiving a gift from the gods.”

* * *

Part of the reason why Stewart seemed more settled was simply because in addition to his professional life becoming more established, the same thing was happening in his personal life. He and his girlfriend, Tracey, were now living together in a loft in downtown Manhattan, and they were engaged to be married.

One of the things that won her heart from the beginning was when they played games together.

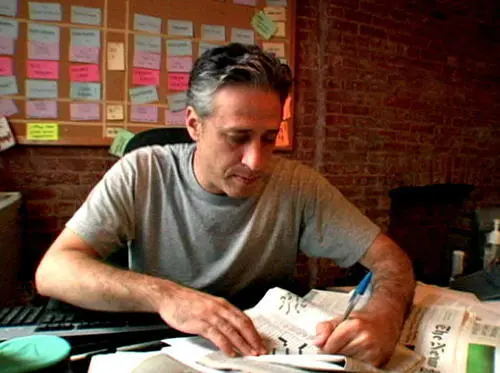

He had proposed in a unique way: he asked Will Shortz, the crossword editor of the New York Times, for help. They had met previously when they were both guests on Late Night with Conan O’Brien and became friends. A few months later, Stewart asked Shortz if he could drop a few hints into an upcoming crossword puzzle since both he and Tracey loved to work on the puzzle each day.

“It was two days before Valentine’s Day and Jon comes home and says, ‘I remembered to bring those crossword puzzles home,’” said Tracey. “As I start to fill it out, there are all these words in it that relate to us.”

“There were [a few] little things in there that related to her,” he said.

One of the hints was “1969 Miracle Met baseball player Art.” The answer, Shamsky, also referred to their dog named Shamsky, who Stewart referred to as his best friend. Shamsky was a rescued pit bull who Stewart claimed was agoraphobic and needed much coaxing to go outside.

“They’re very misunderstood animals,” he said. “At the pound in New York, they’re pretty much the most common animal, I’m sorry to say. People think of them as vicious soldiers, but they’re actually quite sweet and playful. People get them for certain purposes that they don’t work out for and then they discard them. Shamsky unfortunately was not treated particularly well early in life, so I think she has some residual emotional damage. Although you could say that probably about most people you meet.”

Another hint in the puzzle was “tool company,” which pertained to their cat named Stanley. “Then another clue was ‘Valentine’s Day Request,’ and it’s ‘Will you marry me?’” said Tracey. “[The next] clue was ‘Recipient of the Request.’ I look at it saying, ‘It almost looks like my name could fit in there.’”

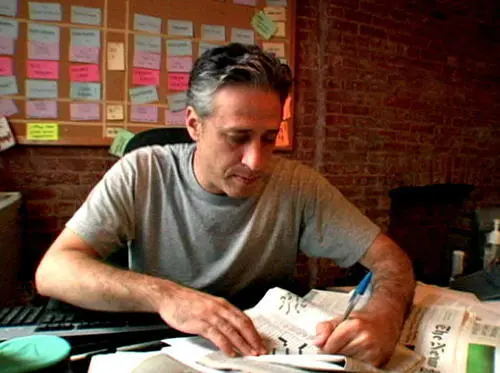

Stewart works diligently on one of his favorite pastimes—the New York Times daily crossword puzzle—in Wordplay , a documentary about the newspaper’s puzzle editor Will Shortz. (Courtesy REX USA/c.IFC Films/Everett)

It did. They were married in 2000.

He was so grateful for his newly happy, settled life that he finally buckled down under Tracey’s pressure and quit smoking cold turkey that same year. “I didn’t realize it at the time, but after you cut out smoking, drinking, and drugs, you feel much better,” he said.

He was profoundly grateful for finding Tracey. “Let me put it this way, I know that I married up,” he said. “And I know how women felt about me before television. When I was a bachelor, I did fine, but usually it had to do with the fact that I was bartending or had a show.”

As they prepared to start a family, they filed a motion with the court to change both of their names to Stewart; legally, Jon was still known as Leibowitz, and some speculated that he made the change in order to put one more step between him and his still estranged father, especially since he was eagerly looking forward to becoming a father himself.

Читать дальше