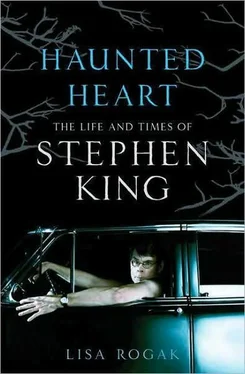

Does he write for a particular person? While he admits that he writes to vanquish his fear, and writing for an audience of one—himself—he has occasionally provided a glimpse of the real man behind the curtain, a man whom Steve has no real recollection of: his father, who walked out of the family home one evening for a pack of cigarettes and kept on going, leaving his wife and two sons—David, age four, and Steve, two—to fend for themselves throughout a childhood of wrenching poverty and great uncertainty.

“I really think I write for myself, but there does seem to be a target that this stuff pours out toward,” he said. “I am always interested in this idea that a lot of fiction writers write for their fathers because their fathers are gone.”

Steve coped with a difficult childhood by turning first to books and then to writing his own stories. And as he put it, it’s a world that he has never really left.

“You have to be a little nuts to be a writer because you have to imagine worlds that aren’t there,” he said. “You’re hearing voices, you’re making believe, you’re doing all of the things that we’re told as children not to do. Or else we’re told to distinguish between reality and those things. Adults will say, ‘You have an invisible friend, that’s nice, you’ll outgrow that.’ Writers don’t outgrow it.”

So who is Stephen King, really? The standard assumption of casual fans and detractors is that he must be a creepy man who loves to blow things up in his backyard. Loyal fans usually go a bit deeper, knowing him to be a loyal family man and a benefactor to countless charities, many around his Bangor, Maine, home.

His friends, however, present a different, more complex picture.

“He’s a brilliant, funny, generous, compassionate man whose character is made up of layer upon layer,” says longtime friend and coauthor Peter Straub. “What you see is not only not what you get, it isn’t even what you see. Steve is a mansion containing many rooms, and all of this makes him wonderful company.”

According to Bev Vincent, a friend whom Steve helped out with Vincent’s book The Road to the Dark Tower, a reference guide to King’s seven-volume magnum opus, his self-image is somewhat surprising: “Steve still sees himself as a small-town guy who has done a few interesting things but doesn’t think that his personal life would interest anyone.”

And he doesn’t understand why anyone would want to read an entire book about him—let alone write one. On the other hand, he has no problem if people want to discuss his work, either face-to-face or in a book.

But we all know he’s wrong. Stephen King has led an endlessly fascinating life, and because we love, admire, and are scared out of our minds by his books, stories, and movies, of course we want to know more about the man who’s spawned it all. Who wouldn’t?

This is a biography, a story of his life. Of course his works play into it, they are unavoidable, but they are not the featured attraction here. Stephen King is.

Through the years, Steve’s fans have been legendary for taking him to task whenever he’s gotten the facts wrong in his stories. For instance, in The Stand, Harold Lauder’s favorite candy bar was a PayDay bar. At one point in the story, Harold left behind a chocolate fingerprint in a diary at a time when the candy contained no chocolate. In the first few months after the book was published, Steve received mailbags full of letters from readers to inform him of his mistake, which was remedied in later editions of the book. And then of course, the candy company began to make PayDays with chocolate. Though some might claim Steve was prescient, you can’t blame the man; after all, this is a guy who isn’t exactly fond of doing research when he’s deep into the writing of a novel. “I do the research [after I write],” he said. “Because when I’m writing a book, my attitude is, don’t confuse me with facts. You know, let me go ahead and get on with the work.”

On the other hand, his lack of concern with the facts of both his fictional and real lives has proved to be more than a bit frustrating to me and other writers. In researching this biography, I’ve attempted to check and double-check the facts of his life, but whether it’s the natural deterioration of memory that comes with age or two solid decades of abusing alcohol, cocaine, and other drugs in various combinations, the guy can’t be faulted for fudging a few dates here and there.

For example, in On Writing, he wrote that his mother died in February 1974, two months before Carrie was first published. However, I have not only a copy of his mother’s obituary but her death certificate, both of which show that she most definitely died on December 18, 1973, in Mexico, Maine, at the home of Steve’s brother, Dave.

Once I knew I was going to be writing about King’s life, I got busy. I dug up old interviews in obscure publications that only published one issue back in 1975, read numerous books, and watched almost all of the movies based on his stories and novels—good and bad, and, boy, the bad ones can be a hoot. I also plunged into the many books that have been written about him and his work since the early eighties. As with the films, there are some good ones and some that are not so good.

The thing that struck me was not the blood and guts and special effects; the gory scenes in his books and movies weren’t as bad as I’d imagined they would be. And it wasn’t his ability to draw and develop characters; I already knew that was one of his particular talents.

What really got me was how funny the man is. I mean, really funny. Yes, his use of pop-culture references and brand names can be amusing when placed side by side with a guy who has a cleaver sticking out of his neck, or as with a corpse in an office setting with an Eberhard pencil stuck in each eye, but his sense of humor just knocked me over. I fell off the couch when the ice cream truck in Maximum Overdrive started playing “King of the Road,” and again in Graveyard Shift when rats are trying to stay on top of broken planks coursing down a fast-moving stream in the middle of a mill’s floor and the music playing is “Surfin’ Safari” by the Beach Boys. King did not write the screenplay for the latter, but you just know his long arm of influence made it into the film.

Steve has gone on the record countless times to say that the one question he hates most is “Where do you get your ideas?” To me as a biographer, all you have to do is ask, “Is it authorized?” to make my face screw up like King’s after an awestruck fan has asked him the idea question.

No, this biography is not authorized. The running joke among biographers is that if it is authorized, the book makes a good cure for insomnia. King does know about this book and told his friends that they could talk with me if they desired. I visited Bangor over several gray, bleak November days in the fall of 2007 to check out all of the key Stephen King haunts. In other words, all the highlights on the local Stephen King tours. It was sheer serendipity that one morning I found myself sitting in his office in the former National Guard barracks out near the airport, with his longtime assistant Marsha DeFillipo grilling me about my aim for this book.

For most of that half-hour interrogation, the man himself hovered just outside the doorway, listening in on our conversation but never once stepping inside.

In the end, perhaps the most surprising thing about Stephen King is that he is a die-hard romantic, which is evident in all of his stories. And to the surprise of his millions of fans, he would be the first to admit it, though to hear him explain it, maybe it’s not really much of a revelation.

Читать дальше