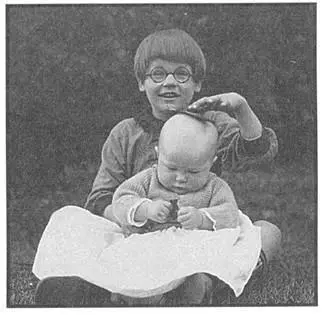

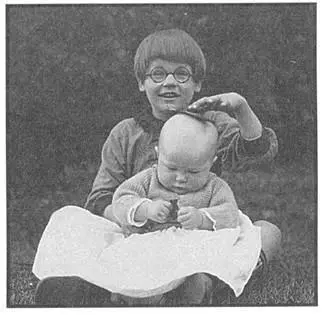

Carol and her younger sister, Janice, photographed in late 1925

Although The Child Who Never Grew makes no mention of my father’s feelings about Carol, I know that both Pearl and Lossing were concerned about her slow development and her inability to learn past a certain level. Both searched for answers to the enigma that was my sister. Being a very strong-willed person who was unable to admit defeat or accept this reality, my mother searched continuously for explanations, looking for a miracle to make her child well. Lossing, on the other hand, could immerse himself in his work. He had come to Nanking in 1916, determined to teach and to introduce American methods of agriculture, especially in the wheat-growing region of China. Since then he had become acting dean and instructor in Agricultural Economics, Farm Management, Rural Sociology, and Farm Engineering at the university in Nanking. Lossing had a long and distinguished career and became well-known in China for his work.

Another reason that Lossing was not included in my mother’s account is that their paths were slowly going in separate directions during this time. Pearl was beginning to develop her potential as a writer, as she needed to find an outlet for her own deep-rooted insecurity. The parting did not become a reality for several more years after Carol left home, but their break-up was a narrative thread that my mother obviously did not want to weave into the story.

During the years after my parents’ divorce, there was little, if any, communication between the two, and I was forbidden to have any relationship with Lossing from the moment my mother and I left China. Lossing remained in China and eventually remarried. He and his Chinese wife had two very bright children who never displayed any genetic problems. It was not until we were reunited after my mother’s death in 1973 that I learned how much he had missed me and my sister. He gave me some early photographs of Carol and me that he had kept all these years, even though my mother had asked him to return all his family photos after the divorce. Lossing died in November, 1975, but not before we had had a chance to renew our family ties. I do not remember that day in 1929 when Carol was taken from me. I was only four, and she was nine, when she was placed in an institution — the Training School at Vineland, New Jersey. Although I realize now that it was for the best, Carol’s departure broke up a family within which we each felt comfortable. Carol and I were as close as sisters should be, even though I was too young to recognize or express my feelings.

The years passed slowly, as I continued in my path from boarding school to boarding school. Because I spent so much time away from home, I did not have the opportunity to visit with my sister as I would have wished. But then again, I did not see much of my parents or other siblings, either. My siblings were eleven and twelve years younger than I was, and we had few interests in common.

For many years, my main contact with Carol occurred in the summer, when she would come home to Pennsylvania for visits of a week or so. The housemother from the Training School always came along to supervise her care, as nobody was ever sure how well Carol would adapt to our family, or our family to her. All in all, I think we adapted fairly well. Carol seemed to recognize us during her visits, and we included her in activities such as playing in the wading pool. But we knew that she had her own life, and it was no longer a part of ours. Usually she kept to herself and her own activities.

When I entered Antioch College in Ohio, I, too, found my own life. There I learned about Occupational Therapy, a new field that combined two interests of mine — medicine and the creative use of the mind through the workings of one’s own hands. After several years of learning and internship, I became an Occupational Therapist, and have worked in this field since early 1949. For many years, I worked with psychiatric patients, then in Geriatrics, and now, for the past seven years, with the mentally retarded.

About a year after I had launched my career, the first edition of The Child Who Never Grew was released. Strange as it may seem, I have no recollection of its publication. One reason may be that I was no longer living at home and was therefore not aware of the flood of letters and visits from parents that the book unleashed. Another reason is that Mother was a prolific writer. I do not remember her ever really discussing any of her books with me, except during the time she used the pseudonym “John Sedges” to write about topics other than China. So, although it may have been a painful struggle for my mother to decide to reveal the truth about Carol, the decision obviously did not harm me in any way.

On one of my brief visits home, sometime in the 1960s, Mother told me that she had learned the reason for Carol’s mental retardation. Carol had an unusual disease called PKU (phenylketonuria). This condition resulted from an inability to metabolize phenylalanine, an essential amino acid. In addition to causing mental retardation, PKU was also associated with blond hair, blue eyes, eczema of the skin, and an overpowering, musty odor, which was perhaps due to the inability to absorb or process protein. (Carol had all of these attributes.) Mother explained that the condition was inherited, and must have been present in both her genes and Lossing’s genes. When we learned about PKU, a method of diagnosing the condition by testing urine samples from the diaper had recently been developed. Today a simple blood test is used to detect the condition in newborns, and a diet low in phenylalanine can prevent mental retardation from developing.

I think my mother had mixed feelings about discovering the cause of Carol’s mental retardation. Mostly I remember her relief at learning that she was not completely to blame. But I also feel that she had trouble accepting that her family’s genes may have contributed to this disorder. Both her brother, Edgar, and her sister, Grace, also had children with handicaps. (One had a child with severe cerebral palsy, and the other, a child who stuttered abnormally.)

Although the test and treatment for PKU were developed too late to prevent Carol’s mental retardation, the title of my mother’s book was somewhat misleading. Despite her PKU, Carol did grow, both physically and mentally. Over the years, I watched her achieve her own potential, thanks to the loving care and concern of the dedicated staff of the Training School at Vineland. They helped her each step of the way, taking to heart their responsibility to ensure the success of those whose lives and growth were entrusted to them.

For most of her life, Carol went to school during the day. She enjoyed school and the activities that were included in her daily routine, and her structured life was good for her. Although I am sure it was not easy to teach her (her attention span was short and she could be strong-minded), she mastered a variety of academic and functional skills over the years. She never learned to read or write, but she did learn to color, write her name, and verbalize her needs. She also learned to sew simple projects and to master many self-care skills that enhanced her independence. She learned to bathe and dress herself with some supervision, to tie her shoelaces, to be independent in toileting and tooth brushing, and to comb and brush her hair with verbal reminders. She also became skilled at using a fork and spoon after she gave up chopsticks, which she preferred for about the first ten years she was at school.

Outside of the classroom, Carol pursued two main interests: music and sports. The love for music described in The Child Who Never Grew continued to deepen until it became, perhaps, Carol’s most calming support. In the playroom in her suite, there was an upright piano on which Mother would play nursery songs while they both sang along. Carol also learned to operate her phonograph and play whatever struck her fancy — whether it be children’s songs, modern music, or classical symphonic music. She actually preferred children’s songs or nursery rhymes and often sang or hummed along with the music. When she did not like a song or a rendition of a song, she would change the record and put it underneath the pile. After records started becoming obsolete, I made sure that Carol always had a radio she could listen to. She enjoyed carrying one around with her, but dropped it often, especially when she forgot to unplug it from the wall. I replaced her radio about twice a year.

Читать дальше