Therefore, I say, we must also fight for the right of our children to be born sound and whole. There must not be children who cannot grow. Year by year their number must be decreased until preventable causes of mental deficiency are prevented. The need is more pressing than the public knows. Our state institutions are dangerously overcrowded and unless research is hastened, millions of dollars must go into more institutions. Even if boarding homes are multiplied, care of these children must be paid for, in the vast majority of cases, by public funds. How much wiser and more hopeful it would be to pay for scientific research which would make such care unnecessary! Let us remember that more than half of the mentally deficient in this country are so from noninherited causes, and these causes can be prevented, did we know what they are. 1

Present care, moreover, is very inadequate. State institutions are able to provide very little of the education that might release a good many of the children to normal, if protected, life. It is not possible to do much educating with an overworked staff in an overcrowded institution. In some states the higher positions in these institutions are still political plums, and the lives of the children are at the mercy of a succession of ignorant men. Private institutions, if they are good ones, are too expensive for the average family.

Yet I believe that the private institution has an indispensable place in our American system. Our notable scientific advance has been the result of private persons working in privately owned places. Public funds have developed very little scientific knowledge except for military purposes. So now I believe that research into this most necessary field, the study of the causes and cure of mental deficiency, must, in accordance with American tradition, take place in small private institutions where scientists can work in freedom. Such research should be co-ordinated so there will be no time wasted in duplication.

Something, of course, has already been done. I have spoken of the notable work of the Research Department at The Training School in Vineland, New Jersey. We know that at least 50 per cent of the mentally deficient children now in the United States can be educated to be productive members of society. Education alone would relieve our overcrowded public institutions. Studies have shown that there are nineteen types of jobs that can be done by an adult whose mentality is no more than that of a six-year-old child. Twenty per cent of all work in the United States is done by the unskilled worker.

We know, too, some of the reasons for injury to the brain, both prenatal and postnatal, but we do not know enough. A little physical remedial work is being done for the injured brains which are the chief causes of mental deficiency, but it is still experimental and confined largely to the limited though important field of cerebral palsy, where the decreased blood supply to the brain is the apparent cause for mental deficiency. 2Results are still too new to be relied upon, but in one institution they were reported as hopeful: 34 per cent of those operated upon showed definite mental improvement, an additional 51 per cent showed changes for the better in alertness, muscular control, interest span, appetite and increased irritability.

I speak of all this merely as grounds for hope, if and when research really begins in the causes and cure for mental deficiency on a scale comparable to that now being done in other fields. Hope is essential for activity.

Those who have children who can never grow — and few are the families who have not one somewhere — must and will work with renewed effort when they realize that more than half the children now mentally deficient need not have been so. They must and will work still harder when they realize that more than half now mentally deficient can, with proper education and environment, live and work in normal society, instead of being idle in inadequate institutions.

Hope brings comfort. What has been need not forever continue to be so. It is too late for some of our children, but if their plight can make people realize how unnecessary much of the tragedy is, their lives, thwarted as they are, will not have been meaningless.

Again, I speak as one who knows.

1[At present, the number of cases of mental retardation caused by inherited factors is not known. According to The ARC, over 350 causes have been identified, but in 75 percent of the cases, the cause of a child’s mental retardation is not known. It is undeniable, however, that the leading cause of mental retardation today — maternal abuse of alcohol or drugs — is preventable.]

2[Today it is known that cerebral palsy can be caused by many types of injuries to the brain before birth, during birth, or shortly after birth. Decreased blood supply is only one possible cause of brain injury.]

Afterword by Janice C. Walsh 1

I REMEMBER THE DAY, in the summer of 1972, when my mother made her last visit to see Carol. She had asked me to drive her down to the school, and my younger sister, Jean, also accompanied us. My mother wanted Carol to get reacquainted with both of us, as she knew that she might not be able to visit again. She was beginning to feel the effects of the lung cancer that was shortly to be diagnosed.

We had arrived at Carol’s cottage, a two-story, yellow-brick building which my mother had endowed to the school many years ago. We were in Carol’s suite, which included a large, light and airy bedroom furnished with a painted French Provincial bedroom set from the 1930s, as well as a small bath, and a playroom with windows on three sides. Mother was seated in a high-backed chair, and Jean on the window seat, while I stood nearby. My mother spoke to Carol slowly and simply, trying to explain who these other visitors were. At first, Carol seemed somewhat perplexed, but then she turned toward me, and in her own authoritative way told me to sit, as Mother repeated my name several times. I watched Carol’s face intently, and saw her expression change from confusion to recognition as Mother spoke the word “Janice.” I knew then that the responsibility had been passed on from mother to daughter. I looked at my mother’s face, and saw the quiet relief and serenity that she had sought in this visit. It was now my time to accept the responsibility; to ensure that Carol would continue to have a family of her own. I would be her link to the past, and to the present.

Some of our shared past is recounted in The Child Who Never Grew. Many years have passed since the book was first published, however, and new chapters have been added to Carol’s life. Mother also left a few unanswered questions in the original story, which can now, I think, be safely answered. This, then, is Carol’s and my story, but mainly Carol’s, drawn from my memories of how she grew.

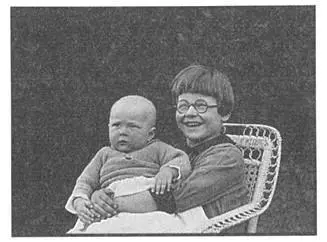

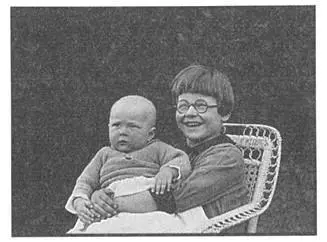

Carol was just five when I was adopted by our parents, Pearl and Lossing Buck. I was a scrawny three-month-old child who had not grown, nor gained much weight since I was born. In fact, I was not expected to survive much past those months. The mother who adopted me wanted a child who would fulfill the expectations her own birth child had been unable to satisfy, and though she had obstacles to surmount, she was determined to achieve her dream.

Carol and I were happy as we grew up in China. We played together, and enjoyed our lives together as we explored the sounds and sights of nature: the sun, the wind, and the earth. But Carol did not grow as a child should grow, and I am sure that I sped past her. I don’t, however, have any recollections that my sister and I were developing at a different pace.

Читать дальше