We can’t find a place to camp. We drive around the empty French countryside. It is late afternoon, the sky still and gray, torpid. Everything seems stunned, anesthetized. We pass a place where little white houses made of corrugated tin rise in rows up a denuded hillside. It is a holiday park. The man tells us they have an area for tents. He is tall and broad and ruddy, like a farmer, but one of his arms dangles shrunken and deformed from his shirtsleeve.

We go into his office, a wooden cabin that stands on a circle of gravel. He writes down our details using his good arm. While we are standing there a family come in. They are Dutch, a well-dressed couple and two fair-haired children. The father instantly starts to shout. He shouts in English. He is shouting at the top of his voice, at the manager of the holiday park, who continues carefully writing. After an interval, the manager looks up. The Dutchman is beside himself: cords of muscle stand out around his neck, and his pale eyes look as though they might fly out of their sockets. He is still shouting: his wife ushers their children outside. He shouts that they have been tricked, deceived, misled. The manager is a villain, a liar. They have come here all the way from Holland, all the way here for a two-week sojourn at the holiday park, and what do they find? I pay attention: I am interested to know what they have found. Despite his aggressive manner, I am even a little sympathetic. I expect him to say that what they found was a dump full of tin huts, instead of the Provençal idyll doubtlessly advertised. But he does not say that. He barks his accusation with a mouth rectangular with rage, like a letterbox. Its substance is that they have been given a different tin hut from the tin hut they booked at home, on the Internet. But monsieur , the manager says with a shrug, the huts are all the same. At this the Dutchman screams. I refer to the position of the hut! The position of the hut is inferior! A fusillade of expletives issues from his mouth. Suddenly I am afraid for the manager. I think the Dutchman is going to kill him. His anger is delinquent, bizarre. He is a narrow, colorless man, a suit. The manager, with his deformity, seems like someone he might choose as a victim. The manager rises from his chair: he is twice the Dutchman’s size. But he is somehow broken, wounded. He doesn’t seem to care whether the Dutchman kills him or not. He has a withered arm; his holiday park is a dump. It would almost be better if that was what the Dutchman was angry about. He tells him to wait; he is going to show us where to put our tent. When he returns, he will see if he can rectify the problem. The Dutchman immediately stalks out of the cabin. Later we see him, standing on the gravel with his family. He is very upright, rigid, as though with the shock of his own significance. His face is white. He has a puny, triumphant air: he has been fobbed off, but he is telling himself that he acted like a man.

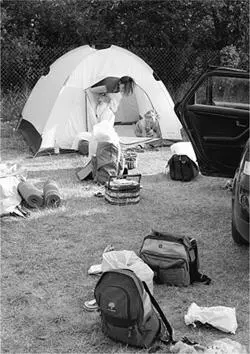

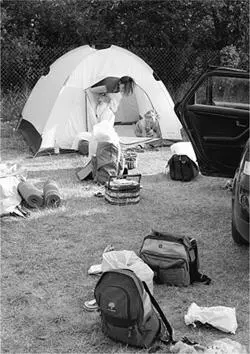

We follow the manager up a dirt road that zigzags interminably through the white tin suburb and then comes out at the top on a stony ledge. The stony ledge is where we are permitted to pitch our tent. It is too late to argue: we put the tent up and get back in the car. It is nearly dark, and we need to find something to eat. There is a village a few kilometers away. When we get there we are surprised to find that it is packed with people. The center is completely closed off. We park the car and walk. In the square a giant screen has been put up, and the buildings are all strung with flags. It is the World Cup final: France are playing Italy. The square is crowded, with old ladies and children, with gangs of kohl-eyed teenagers in black drainpipes and plump middle-aged couples. Everywhere there are shirtsleeved delegations of men locked in endless, cheerful conference.

We find a seat, get beer and food from a stall. We feel a little treacherous, though our treachery is all against Italy. It is not this prosperous French village we are deceiving: we are sure that France will win. They have to win, for much the same reason that we had to leave Italy — because reality requires it. Anything else would be fantastical, improvident. The French have Zidane, rationality, form. These are the things on which expectations can be based and decisions reached. What do the Italians have? I remember the traffic policeman who stood at the mouth of the tunnel with his elaborate braided uniform, his long leather boots, his snowy gloves, his manner that was both theatrical and sincere. He courteously waved us out of his land like an actor at the final curtain. The Italians have splendor. What would a decision be like that had splendor as its basis? To what strange, beautiful expectations would it give rise?

The French do not win the World Cup final. The Italians win. Zidane assaults one of the Italian players, butting him with his white, domed, rational forehead. We return to the rocky ledge, where all night the hard, uneven ground probes our slumber and sends our bodies roaming around the tent, searching for flat places, for relief.

The fields of the Charente are yellow, with chalky white partings like hair. Grain silos stand in their flat distances: they are gray, concrete, shaped like giant hourglasses. Their swollen forms are dominating, implacable. They stand upright between the horizontal planes of field and sky, alone, as though they had devoured everything that was once there.

We come off the motorway at St. Jean d’Angély and skim through the silent, yellow-white landscape. The road is completely straight: it stretches on for as far as the eye can see, pale gray and empty. The children gaze through the open windows. They are very quiet. Now and again a straight line of trees passes, at right angles to the road, and their eyes flicker, mathematically registering the perspective. We have booked a room in a hotel: we arranged it by phone. Tiziana’s tent has been folded into its bag. It is our last night before England, a night for reflection, order, readiness. The world is once more flat and straight, symmetrical. It is bare and clean, blank, like paper. It seems to invite something, some final utterance. What can we say, to the blank yellow-white fields? What should we inscribe along the straight lines of trees?

We follow our directions: at a junction where four narrow white roads depart in four different directions across the flat fields, and where a few stone houses stand at the crossroads displaying pots of red geraniums but no people, we turn left. The road goes straight, into the yellow distances. Now and again there is a right angle, and then a straight section, and then another right angle. We are driving around the perimeters of fields. Sometimes we pass a small white house, sitting behind its fence. After a while we come to a dip, a kind of ripple in the earth. The lines of trees go down and come up again. The expanse of yellow grain describes it with its level, brushlike fibers, this perfect concavity. It falls and rises; it rolls like the sea. How strange and mysterious the world is, describing itself with such rigorous perfection: it is as though description is its ambition, its only purpose. The road enters the dip, descends and comes up again. In front of us there is a screen of dark green trees. The light is chalky, faintly unreal. It gives a kind of flatness to everything, like paint; it describes them, the green trees and the white road, the undulating yellow field. We pass through a pair of stone gates and along a driveway of pale, fine dirt. At the end there is a house. It is a grand house, long and low, light gray, with two rows of shuttered windows. The white, bleaching light is full on its face. The glass in the windows is dark. It is like something someone is remembering. To the left there is a long stone building with high-up windows, like a barn. The terrain is so flat that nothing is visible beyond the screen of trees.

Читать дальше