I sit down on the curbstone, underneath the high wall. It seems that I can go no further. The others stand and look down at me. I perceive their consternation in vague, shadowy blocks with the sun behind like a halo. Then they say that they will go on to ascertain the length of the queue, while I rest here. They go, and a short time later they return. There is no queue. The museums are closed on Sundays. We should have checked: we are losing our touch. We have missed our chance.

For a while we stay where we are, idling on the pavement in the shade. I think of Alberto Moravia’s stories, the Roman Tales , where disappointment is always the springboard to some kind of truth, a truth that lies beyond desire and motivation. The others sit on a bench. I remain on the curbstone. Presently my daughter takes a photograph of me. I look at it sometimes, back in England. I am a woman of thirty-nine, casually dressed, with a white bandage on her foot. The place where I sit, in the right angle of the curb and the wall, is so old that the stones have been worn into rounded shapes. In a minute I am going to get up: I won’t be there anymore. It is almost as though I am not there at all. It is the stones that are really there, not me. Maybe one day I’ll go back and sit in the same place, to prove something. But all the same, I look happy. I am smiling.

We have a tent. It is Tiziana’s: she lent it to us. Before we left to go south, she erected it for us on the grassy slope of her garden, beside the wooden hut. It is a small tent, dome-shaped, faded blue on the outside, with a faded pink interior. The bleached colors are intimate: it is Tiziana’s use that has faded them. We all get inside, while Tiziana’s huge black dogs lie down on the hot grass at the flap. It is like sitting in a shell, or a teacup. The brilliant afternoon disappears: the tent is filled with a diffuse, rose-colored light, and the unbodied sounds of outside, of the dogs panting softly in the heat. Tiziana strokes the worn material, recalling her travels. She has been happy in this tent. She has taken it with her everywhere. She wishes to bequeath it to us, this frail shelter that can simply be unfolded and become a place, as familiar as a room, then cease to exist again. She doesn’t like the thought of it ceasing to exist. We promise to send it when we get back to England, but Tiziana shrugs. She doesn’t think she’ll be camping anytime soon, dug in as she is on Jim’s doorstep, awaiting an opportunity to strike.

It is July, and the summer lies heavy on the landscape; the heat extends everywhere, across night and day, unbroken. We pick up the car in Arezzo and drive to the coast, past the port of Piombino with its ships and steel foundries and boats to Elba, out across the deserted countryside of the headland, and north to remote Populonia and the Gulf of Baratti. The light is dry, ancient, on the earth-colored shoreline. The sea is a sheet of glitter. The tufted green headland, the grassy dunes with their crescent of pine trees, the brown-hillocked mystery of the Etruscan necropolis that stands beside the water, the fortified village on its hill above the bay: it is like a secret fold in the earth, inviolate. We pitch Tiziana’s tent in a big, dry glade with straw-colored fields all around its perimeter, a kilometer from the sea. The pine needles and brown, brittle eucalyptus leaves are soft underfoot. We tie a length of rope between two trees as a washing line. We spread a sheet on the floor of the tent to sleep on. There is a shower block, and a little café that sells cappuccino and cornetti for a euro.

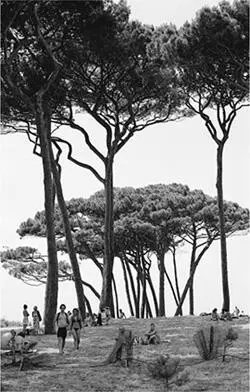

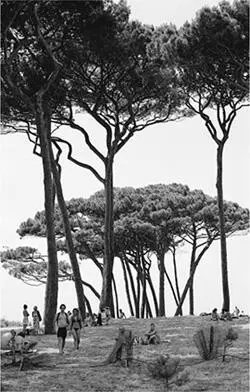

The pine trees in the dunes have umbrella-shaped tops with dark, spur-like branches: their trunks are as thick and tall and fantastical as giants’ legs. Pliny, from his naval vessel in the Bay of Naples, observed that the cloud given off by Vesuvius at its eruption was precisely the shape of an umbrella pine. These trees are ubiquitous in Italy: it is strange that the volcano should mirror their shape, as though a country could have a family of forms, just as it has a distinct language and race of people. The floor of the pinewood is soft and springy: it is undulating, mounded, primitive in appearance. There are people here. They walk soundlessly through the shade with its intricate stencils of light. They tread the narrow paths down to the beach and the sea. The water beats and heaves softly beyond the screen of trees. We follow a path that winds among the giant trunks. We are barefoot, brown-skinned, unburdened. The children carry their swimming towels in a roll under the arm. We have water, and a small secondhand hardback edition of Shakespeare’s plays. We have a home six feet wide made of faded blue cloth, and a washing line. There seems to be no need for anything else. The bay is so warm, so soft, so simple: it releases us from need, like sleep. Is it better to sleep than to need? What was its purpose, all that need, the machinelike complexity of our life at home, the desire for escape that was its dark emission? A warm wind soughs through the pinewood and stirs the high-up branches of the trees. In the distance we can see the humped brown shapes of the Etruscan tombs. Then we come out into the blinding light of the beach, the sand strewn with matted foliage, the water rolling in its frill of surf. The countryside is rough, carefree, running down to the edge of the sand. There are people dotted about. They seem small, indistinct, both vague and multifarious, like forms etched by centuries of tides.

Our copy of Shakespeare has illustrations. They are highly colored, artificial, like stills from an old Hollywood movie. There is a drawing of Julius Caesar in his toga and laurel wreath, craggy and superstitious-looking, his eyes sliding to the side. There is Hamlet, black-clad and thin as a spider, with fair foppish hair. They are realities become characters become realities again. I brought the book to the beach with the intention of reading it myself, but the others want to read it too. The children do not run to the rolling water, nor play in the earthy sand. Instead they sit one on either side of me, their mouths by my ears, trying to see over my shoulder. They want to know about Shakespeare. They want to know the plot of Othello , of Antony and Cleopatra . They point to things and ask what they mean. Every time I turn the page, they complain. After a while I surrender and read aloud. I read them Hamlet’s soliloquies and Antony’s love speeches and Macbeth’s unsettling remarks on the death of his wife. I do all three witches in different voices. I do The Tempest , explaining as I go along.

The afternoon passes. A man comes up the beach selling slabs of frozen pineapple. Later he comes back again, selling lemon granite . People come and go through the heat haze, in and out of the silent pinewoods. The sun begins to dip; slowly light leaves the bay. The sea is milky, thick, mineral-colored. Evening approaches, a blue-gray aura that stands on the hills and fields, as though it has risen from the earth. The tombs cast shadows across the grass. The sun sinks, bloodying the sky. It leaves behind it a feeling of weightlessness, of consciousness desisting. Everything is still, trancelike. The water laps faintly at the shore. There are no lights around the bay; the human day is barely marked. A month might have passed, or a century. We roll up our towels and return to our tent. There are other tents in our glade; people are rinsing out their swimming costumes, heating things on little stoves, reorganizing their pots and pans. They do not relinquish their grip on time. They are standing up for civilization. In the tent next door there is a young German couple, fair and big-boned, who have prepared a hot meal for themselves and are sitting eating it at their folding table, where the glasses and cutlery and pepper pot have been nicely laid out. The girl serves the food to the boy, who sits upright and expectant in his chair. They are so young and yet so proper: I don’t know whether to admire them or feel concerned on their behalf. How rigid and upright they are, how thoroughly disciplined, in this wild bay with its fields of ancient tombs, its giant primeval trees, its centuries that pass in an afternoon. They haven’t turned up here with a volume of Shakespeare, a sheet, and a two-man tent that must somehow accommodate four. They have inflatable mattresses, which I watch the boy pump up after supper.

Читать дальше