Sarah Bakewell - How to Live - A Life of Montaigne in One Question and Twenty Attempts at an Answer

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Sarah Bakewell - How to Live - A Life of Montaigne in One Question and Twenty Attempts at an Answer» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 2011, ISBN: 2011, Издательство: Random House UK, Жанр: Биографии и Мемуары, Критика, Философия, Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:How to Live : A Life of Montaigne in One Question and Twenty Attempts at an Answer

- Автор:

- Издательство:Random House UK

- Жанр:

- Год:2011

- Город:New York

- ISBN:9780099485155

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

How to Live : A Life of Montaigne in One Question and Twenty Attempts at an Answer: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «How to Live : A Life of Montaigne in One Question and Twenty Attempts at an Answer»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Review In a wide-ranging intellectual career, Michel de Montaigne found no knowledge so hard to acquire as the knowledge of how to live this life well. By casting her biography of the writer as 20 chapters, each focused on a different answer to the question How to live? Bakewell limns Montaigne’s ceaseless pursuit of this most elusive knowledge. Embedded in the 20 life-knowledge responses, readers will find essential facts — when and where Montaigne was born, how and whom he married, how he became mayor of Bordeaux, how he managed a public life in a time of lethal religious and political passions. But Bakewell keeps the focus on the inner evolution of the acute mind informing Montaigne’s charmingly digressive and tolerantly skeptical essays. Flexible and curious, this was a mind at home contemplating the morality of cannibals, the meaning of his own near-death experience, and the puzzlingly human behavior of animals. And though Montaigne has identified his own personality as his overarching topic, Bakewell marvels at the way Montaigne’s prose has enchanted diverse readers — Hazlitt and Sterne, Woolf and Gide — with their own reflections. Because Montaigne’s capacious mirror still captivates many, this insightful life study will win high praise from both scholars and general readers. -Bryce Christensen

“This charming biography shuffles incidents from Montaigne’s life and essays into twenty thematic chapters… Bakewell clearly relishes the anthropological anecdotes that enliven Montaigne’s work, but she handles equally well both his philosophical influences and the readers and interpreters who have guided the reception of the essays.”

— “Serious, engaging, and so infectiously in love with its subject that I found myself racing to finish so I could start rereading the Essays themselves… It is hard to imagine a better introduction — or reintroduction — to Montaigne than Bakewell’s book.”

—Lorin Stein, “Ms. Bakewell’s new book,

, is a biography, but in the form of a delightful conversation across the centuries.”

— “So artful is Bakewell’s account of [Montaigne] that even skeptical readers may well come to share her admiration.”

— “Extraordinary… a miracle of complex, revelatory organization, for as Bakewell moves along she provides a brilliant demonstration of the alchemy of historical viewpoint.”

— “Well,

is a superb book, original, engaging, thorough, ambitious, and wise.”

—Nick Hornby, in the November/December 2010 issue of “In

, an affectionate introduction to the author, Bakewell argues that, far from being a dusty old philosopher, Montaigne has never been more relevant — a 16th-century blogger, as she would have it — and so must be read, quite simply, ‘in order to live’… Bakewell is a wry and intelligent guide.”

— “Witty, unorthodox…

is a history of ideas told entirely on the ground, never divorced from the people thinking them. It hews close to Montaigne’s own preoccupations, especially his playful uncertainty — Bakewell is a stickler for what we can’t know…

is a delight…”

— “This book will have new readers excited to be acquainted to Montaigne’s life and ideas, and may even stir their curiosity to read more about the ancient Greek philosophers who influenced his writing.

is a great companion to Montaigne’s essays, and even a great stand-alone.”

— “A bright, genial, and generous introduction to the master’s methods.”

— “[Bakewell reveals] one of literature's enduring figures as an idiosyncratic, humane, and surprisingly modern force.”

—

(starred)

“As described by Sarah Bakewell in her suavely enlightening

Montaigne is, with Walt Whitman, among the most congenial of literary giants, inclined to shrug over the inevitability of human failings and the last man to accuse anyone of self-absorption. His great subject, after all, was himself.”

—Laura Miller, “Lively and fascinating…

takes its place as the most enjoyable introduction to Montaigne in the English language.”

— “Splendidly conceived and exquisitely written… enormously absorbing.”

— “

will delight and illuminate.”

— “It is ultimately [Montaigne’s] life-loving vivacity that Bakewell succeeds in communicating to her readers.”

—The Observer

“This subtle and surprising book manages the trick of conversing in a frank and friendly manner with its centuries-old literary giant, as with a contemporary, while helpfully placing Montaigne in a historical context. The affection of the author for her subject is palpable and infectious.”

—Phillip Lopate, author of “An intellectually lively treatment of a Renaissance giant and his world.”

— “Like recent books on Proust, Joyce, and Austen,

skillfully plucks a life-guide from the incessant flux of Montaigne’s prose… A superb, spirited introduction to the master.”

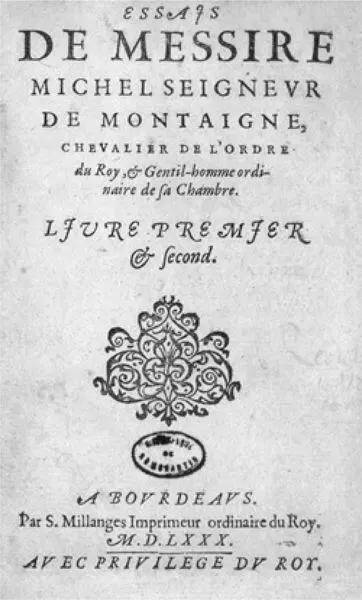

— In a wide-ranging intellectual career, Michel de Montaigne found no knowledge so hard to acquire as the knowledge of how to live this life well. By casting her biography of the writer as 20 chapters, each focused on a different answer to the question How to live? Bakewell limns Montaigne’s ceaseless pursuit of this most elusive knowledge. Embedded in the 20 life-knowledge responses, readers will find essential facts — when and where Montaigne was born, how and whom he married, how he became mayor of Bordeaux, how he managed a public life in a time of lethal religious and political passions. But Bakewell keeps the focus on the inner evolution of the acute mind informing Montaigne’s charmingly digressive and tolerantly skeptical essays. Flexible and curious, this was a mind at home contemplating the morality of cannibals, the meaning of his own near-death experience, and the puzzlingly human behavior of animals. And though Montaigne has identified his own personality as his overarching topic, Bakewell marvels at the way Montaigne’s prose has enchanted diverse readers — Hazlitt and Sterne, Woolf and Gide — with their own reflections. Because Montaigne’s capacious mirror still captivates many, this insightful life study will win high praise from both scholars and general readers. -Bryce Christensen Named one of Library Journal’s Top Ten Best Books of 2010 In a wide-ranging intellectual career, Michel de Montaigne found no knowledge so hard to acquire as the knowledge of how to live this life well. By casting her biography of the writer as 20 chapters, each focused on a different answer to the question How to live? Bakewell limns Montaigne’s ceaseless pursuit of this most elusive knowledge. Embedded in the 20 life-knowledge responses, readers will find essential facts — when and where Montaigne was born, how and whom he married, how he became mayor of Bordeaux, how he managed a public life in a time of lethal religious and political passions. But Bakewell keeps the focus on the inner evolution of the acute mind informing Montaigne’s charmingly digressive and tolerantly skeptical essays. Flexible and curious, this was a mind at home contemplating the morality of cannibals, the meaning of his own near-death experience, and the puzzlingly human behavior of animals. And though Montaigne has identified his own personality as his overarching topic, Bakewell marvels at the way Montaigne’s prose has enchanted diverse readers — Hazlitt and Sterne, Woolf and Gide — with their own reflections. Because Montaigne’s capacious mirror still captivates many, this insightful life study will win high praise from both scholars and general readers.

—Bryce Christensen