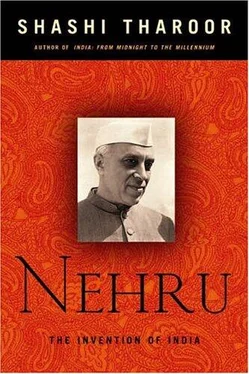

Tharoor Shashi - Nehru - The Invention of India

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Tharoor Shashi - Nehru - The Invention of India» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2004, Издательство: Arcade Publishing, Жанр: Биографии и Мемуары, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Nehru: The Invention of India

- Автор:

- Издательство:Arcade Publishing

- Жанр:

- Год:2004

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Nehru: The Invention of India: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Nehru: The Invention of India»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Nehru: The Invention of India — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Nehru: The Invention of India», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The Congress election manifesto made no mention of socialism. What it did focus on was the constitutional system built into the Government of India Act, in particular the pernicious Communal Award, under which the British had again sought to divide Indians by creating seventeen separate electorates for different communities. The principal purpose of seeking election, the Congress declared, was to undo this British perfidy by wrecking the constitutional system from within and demanding full freedom and unfettered democracy rather than political half-measures.

The allocation of seats under the Act was deliberately stacked against the Congress, in particular by arrangements giving the Muslims and other minorities (and therefore the parties seeking to represent such narrower identities) a larger number of seats than their proportion of the population would have warranted; and the rural poor, Gandhi’s natural base (and to a great extent Jawaharlal’s), were denied the vote altogether. Yet the election results exceeded the expectations of even the most optimistic Congressman. The Congress Party contested 1,161 of the 1,585 seats at stake; it won 716, an astonishing 62 percent of the seats contested. This was despite restrictions on the franchise, which gave disproportionate influence to the educated and the well-off by granting the vote to only 36 million out of India’s 300 million population, and the active hostility of the governmental machinery. Further, the Congress emerged as the largest single party in nine of the eleven provinces; in six of them it had an outright majority. Jawaharlal interpreted this as a mandate to reject the Government of India Act and demand a Constituent Assembly instead, but his partymen preferred immediate office to future freedom — jam today rather than bread tomorrow. They accepted his draft resolution describing the election results as a repudiation of the Act, but added a clause (dictated by Gandhi) authorizing Congressmen to take office in each province if they were satisfied that they could rule without interference by the British-appointed governor. Once again Jawaharlal came close to resigning. Once again, he chose to put party unity ahead of his own convictions. (“Just as the King can do no wrong,” he said after having been outvoted by his colleagues, “the Working Committee can do no wrong.”) In July 1937, Congress ministries were formed in six provinces.

Meanwhile, the Muslim League had awoken from a long slumber. After years of inactivity crowned by political success (since the British government tended to grant the League’s princely leaders everything they asked for, and in the Communal Award actually exceeded the League’s own requests) the party’s grandees began to take note with concern of the mass mobilization led by the Congress. In response, they invited Jinnah back from his long self-exile in London and made him “permanent president” of the League in April 1936.

The British government was not averse to this development. As early as 1888, the Congress’s founder, Allan Octavian Hume, felt obliged to denounce British attempts to promote Hindu-Muslim division by fostering “the devil’s doctrine of discord and disunion.” The strategy was hardly surprising for an imperial power. “ Divide et impera was the old Roman motto,” wrote Lord

Elphinstone after the 1857 Mutiny, “and it should be ours.” Promoting communal discord became conscious British policy. In December 1887 — at a time when the Congress’s first Muslim president, Badruddin Tyabji, was striving to unite Hindus and Muslims in a common cause — the pro-British judge and Muslim educationist Sir Syed Ahmed Khan was arguing in a speech in Lucknow that the departure of the British would inevitably lead to civil war. The numerical advantage of Hindus over Muslims, he argued, would give them unfair advantage in a democratic India; imperial rule by the Christian British, fellow “people of the book,” was therefore preferable. In 1906, a deputation of Muslim notables led by the Aga Khan and seeking separate privileges for Muslims was received by the British viceroy, and the Muslim League was born.

But in its thirty years of existence, the League had failed to become a potent force in national politics. Jinnah formulated an effective strategy to raise the League to political prominence as the “third party” in a struggle involving the British and the Congress. He argued that he too was an Indian nationalist who sought greater rights from the British, but he aimed to achieve these by constitutional means, while protecting the interests of the Muslim community. In his public speeches he portrayed the Congress as a Hindu-dominated party whose triumph would threaten the religious identity of Indian Muslims and displace their preferred language, Urdu. More privately, he was not averse to suggesting to the League’s affluent patrons that Jawaharlal Nehru’s dangerous socialism was a threat to the economic interests of the Muslim landed and commercial elites. Nehru bridled at what he saw as Jinnah’s pretensions, challenging the representativeness of the League’s leadership: “I come into greater touch with the Muslim masses,” he declared acidly, “than most of the members of the Muslim League.” Asserting the Congress’s claim to speak for all Indians of whatever faith, he rejected the notion that the League (a “drawing-room party”) had any valid place: “There are only two forces in the country, the Congress and the Government. Those who are standing midway shall have to choose between the two.”

Jawaharlal’s contempt was based both on his distaste for communal bigotry (he often condemned the Hindu Mahasabha, the principal political vehicle of Hindu chauvinism, in the same breath) and his political judgment. The latter was borne out by the 1937 election results. Under the British provisions for separate communal electorates, 7,319,445 votes were cast by Muslim voters for Muslim candidates; only 4.4 percent of these, 321,772, went to the Muslim League. In other words, the League had been overwhelmingly repudiated by the very community in whose name it claimed to speak. Instead Muslim voters had voted for a wide variety of other parties, from the landholding Unionists in the Punjab to a peasants and tenants’ party in Bengal, and even for the Congress, which foolishly had run very few Muslim candidates (it put up 58 candidates in the 482 seats reserved for Muslims and won 26 of those races). Victorious Muslim politicians were more interested in securing power in their provinces than in supporting Jinnah’s advocacy of a pan-Indian Muslim identity.

In mid-1937, therefore, the League was not a serious threat to Congress ascendancy. Defeated in his wish to keep his party out of British-supervised ministerial office (under a Constitution that did not even grant Dominion status, let alone independence), Jawaharlal stayed president of the Congress but went into the political equivalent of a sulk. He was in fact away on a tour of Burma and Malaya when the decision to accept office was taken by his colleagues. He refused to serve on the Congress Parliamentary Board which was set up to give party guidance to the provincial ministries. Yet he became caught up in one of the most controversial episodes of his political career — the failure of the Congress to accept the offer of the Muslim League to form a coalition government in Jawaharlal’s own province, U.P.

The League had won twenty-seven of the sixty-four Muslim seats in the U.P. legislature; the Congress, which had only run nine Muslim candidates, had won none, but it had enjoyed overwhelming success in the “general” seats (those not reserved for any particular community) and, with a majority in the legislature as a whole, was in a position to form a ministry on its own. As party president, Nehru initiated a “mass contact” program for Congress workers with the Muslim population, in order to bring more of them into the nationalist movement. The League saw this as a threat; its political success depended on its being able to credibly claim that it was the sole spokesman for India’s Muslims. The two visions were clearly incompatible, yet the League began negotiating with the Congress to form a joint government in which the League would nominate two Muslim ministers. The lead Congress negotiator was a Muslim, Maulana Azad; the lead League negotiator was Chaudhuri Khaliquzzaman, formerly a close friend of Jawaharlal’s who had often enjoyed his hospitality, staying at Anand Bhavan whenever he visited Allahabad. The two negotiators came close to an agreement. The League was even willing to merge its identity in the provincial legislature with that of the Congress, but the deal finally foundered on the League’s insistence that its legislators would be free to vote differently on “communal issues.”

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Nehru: The Invention of India»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Nehru: The Invention of India» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Nehru: The Invention of India» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.