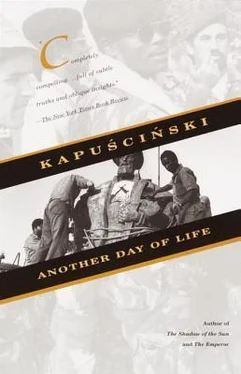

All our enemies feed on the backwardness of the people, he says, and pay handsomely to keep the tribal wars going without end. They bought Holden Roberto so he’d create the FNLA from the Bakonga. They bought Savimbi to create UNITA from the Ovimbundi. We have a hundred tribes and must build one nation out of them. How long will it take? Nobody knows. We have to wean the people from hatred. We have to introduce the custom of shaking hands.

This is an unlucky country, he continues, just as there are unlucky people whose lives just don’t want to work out. The Portuguese were constantly organizing armed expeditions to conquer all Angola over the last two hundred years. There’s been no peace. We’ve been fighting a guerrilla war for fifteen years. No country in Africa has had such a long war. None has been so devastated. There were never many of us guerrillas. Then some died and others left for headquarters or the government. Only a handful of the old cadres remained at the front. We are scattered all over the country. We are short of people.

The troops with me are boys taken straight from the streets to the front. They ought to be in school, but we closed the schools in order to have an army, since we have to defend ourselves. This war was forced on us because we are a rich country inhabited by five million poor people, benighted illiterates incapable of operating an 86-mm recoil-less rifle. The other side thinks it’ll only take twenty armored vehicles to go on having our oil and diamonds and to put us back in our place. They didn’t give us time for anything, we have green troops who have to grow up to fight. For me, it’s a waste of these boys because they ought to grow up to read and write, to build towns and make people healthy. But they have to grow up to kill. They have to grow up to having less and less blind shooting on our side and more and more death on the other side. What other way out do we have in this war that we never wanted?

I am in Caxito, over sixty kilometers north of Luanda. Comandante Ju-Ju telephoned this morning to say there had been a battle for Caxito at dawn, that Comandante Ndozi’s unit had seized the town from the FNLA and it would be possible to go there presently. Ju-Ju is the political commissar of the MPLA general staff and he reads a communiqué on the war situation over the radio at eight each evening. These communiqués sound high-flown because Ju-Ju puts his heart and soul into them. One day we were weeping over the death of the late lamented Comandante Cowboy, who fell in the assault on the town of Ngavi. The intrepid hero refused to take cover and, severely wounded, dealt out death to three bestial aggressors. The next day we are celebrating the triumph at Folgares, where our glory-bedecked army delivered a shattering blow to a band of venal mercenaries. On another occasion we learn that all Africa is following with bated breath the fate of the heroic garrison in Luso, which has resolved to yield not an inch of ground to the numberless horde surrounding it. Our spirit will never weaken, our will to fight is inflexible as steel, we do not know fear, we do not fear death, and we are perishing in the eyes of an admiring world.

Ju-Ju’s communiqués are brief and calm when things are going well. The facts speak for themselves, and you don’t have to beg people to back a winner. But when something turns rotten, when it starts going bad, the communiqués become prolix and crabbed, adjectives proliferate, and self-praise and epithets scorning the enemy multiply. Ju-Ju’s voice reaches out to me through open windows as I walk the streets of Luanda. At this distance I can’t make out the words, but the fact that he talks for only a moment tells me that it’s good, that they are holding out, that they have taken something. But yesterday I covered half the city while Ju-Ju went on and on. Something had obviously gone wrong at the front. A thousand doubts descended on me: Would they manage to stick it out? Would they win?

Ju-Ju is a white Angolan, which means that his family comes from Portugal but he was born in Angola, which is his homeland. There are hundreds like him in the MPLA. They fight at the front or work in the staff or in administration. They all wear beards. That is a mark of identity here: a white with a beard is from Angola and nobody asks for his documents or pulls him in for interrogation. The blacks call him “camarada” and treat him with respect, because if he’s a white with a beard he must be somebody, the leader of a unit or higher. Ju-Ju has a beard like a Byzantine patriarch — down to his chest, impressive. That beard is the most striking thing about him, because he is small, thin, and stooped; he wears thick glasses and resembles a lecturer in the department of classical languages at one of the older European universities.

During the conquest of Caxito, Comandante Ndozi’s unit took 120 FNLA prisoners; Ju-Ju is interrogating them. They are summoned one by one under a large chestnut tree, where the political commissar is seated on an ammunition crate (grenades, French manufacture, captured from the enemy). By nature a shy man, Ju-Ju speaks politely or even deferentially to each of them and concludes the conversation by imparting a lesson, in the hope that it will lead the prisoner into the correct road of life and endeavor. He begins by evoking feelings of shame and guilt in his subject.

“Aren’t you ashamed,” the political commissar asks, “to be fighting in the FNLA as an agent of imperialism?”

A glum, vacant-looking Bakongo with skin so black that it shades toward violet, and a mug ugly enough to make your flesh crawl, says nothing and stares at the ground. He adjusts a bloody rag tied around his head where a bullet has taken one of his ears off. He sighs and seems ready to cry, but still says nothing.

Ju-Ju encourages him to talk, insists, even offers him a cigarette, although cigarettes are a priceless treasure in Angola and you can save your life for a pack or even half.

The prisoner answers at last that in Kinshasa (in Zaïre) they make roundups of Angolan Bakongos and press-gang them into the FNLA. Mobutu’s troops conduct these roundups. Whoever has the francs can buy his way out, but he didn’t have the francs because he was unemployed, so when they caught him they press-ganged him. It was good in the FNLA because they gave you something to eat. They give you manioc and lamb. On Saturdays they give you beer. If you win a battle, you get money. But he wasn’t in any battles they got paid for. He stole nothing, because everything was already looted and empty from the Zaïrian border to Caxito. He never saw Holden Roberto. He doesn’t know how to read and write. They were surrounded this morning, so they surrendered and here they are. He didn’t kill anybody.

Ju-Ju orders the next one brought in: a Bakongo, with hair that begins right above his eyebrows, reeling in terror. The commissar asks if he isn’t ashamed, etc., then asks where the nearest FNLA troops are.

This one doesn’t know. It was so mixed up that he doesn’t know who was captured and who got away. One mercenary shouted at him, “That way, that way,” and he obeyed and ran right into the MPLA, while the mercenary took off in the other direction and escaped. Among his fellow prisoners, he knows nobody. He and four others were sent from Ambriz to Caxito. They had nothing to eat or drink, because there is nothing on that road. Three died of exhaustion. One disappeared at night. He was left alone. He arrived in Caxito last evening. He wants to drink. He thinks that if there are any FNLA nearby, they will give up tomorrow on their own because there is no water in the vicinity except in Caxito. They will hold out overnight and perhaps until noon, then they will come in because otherwise they’ll die of thirst.

The next prisoner looks twelve. He says he’s sixteen. He knows it is shameful to fight for the FNLA, but they told him that if he went to the front they would send him to school afterward. He wants to finish school because he wants to paint. If he could get paper and a pencil he could draw something right now. He could do a portrait. He also knows how to sculpt and would like to show his sculptures, which he left in Carmona. He has put his whole life into it and would like to study, and they told him that he will, if he goes to the front first. He knows how it works — in order to paint you must first kill people, but he hasn’t killed anyone.

Читать дальше