describing how the great city of St. Petersburg was built, how the mythos of this wonder was created, and how classical Russian literature from Pushkin to Dostoyevsky boldly and brilliantly interpreted the image of the city and, in the end, profoundly changed it.

Alexander Pushkin was nervous and angry. The poet was in the second week of his self-imposed exile in Boldino, the small steppe estate of his father some six hundred miles from Petersburg. Pushkin’s purpose in coming here was to write poetry, in solitude and peace, far from the bustle of the capital. But the verse, spitefully, wouldn’t come. His head ached, his stomach hurt; could it be the heavy Russian diet—potatoes and buck-wheat groats?

He was worried about his substantial debts. The only way to get rid of them was to hope for inspiration from God, to produce something significant, and then sell that “something” profitably to his Petersburg publisher. But it was difficult for Pushkin to concentrate on poetry; he was tormented by jealousy, obsessed with worry about his young wife, who remained in Petersburg. The famous beauty, Natalya, was flattered by the attentions of the social lions, while the temperamental Pushkin naturally climbed the walls. He crudely berated his wife in a letter from Boldino: “You’re pleased that studs chase after you like a bitch, their tails stiff up in the air and sniffing your ass; nothing to be happy about! … If you have a trough, the pigs will come.” {8} 8 1 A. S. Pushkin, Polnoe sobranie sochinenii (Complete Collected Works), vol. 10 (Moscow, 1951), pp. 453-54.

The dreary autumn weather would have plunged anyone into deep depression. But Pushkin, despite his African ancestry, loved the northern clime. He hoped that the Russian autumn would bring him inspiration, as it always had. It tormented him first, then paid off; verse finally came. The happy poet awoke at seven in the morning, worked in bed until three in the afternoon, then rode horseback in the mud for two hours, cooling off his head, overheated with ideas.

“I started writing and have already written tons,” {9} 9 2 Ibid., p. 454.

he announced proudly to his wife in a letter to Petersburg dated October 30, 1833. The next day at dawn, in his quick but beautiful hand, he finished the fair copy of his narrative poem, The Bronze Horseman. We know that because of the notation on the final page: “five after five a.m.” (that is, contrary to his habit, the poet had worked all night).

Pushkin rarely documented his work with such accuracy. Apparently, even he, who never underestimated his genius, understood that in those twenty-six October days he had achieved something unique and extraordinary. (Which may also be why he asked five thousand rubles from his publisher upon returning to Petersburg, an unheard of sum in those days.) The poet’s intuition did not fail him: The Bronze Horseman is still the greatest narrative poem written in Russian. It is also the beginning and at the same time the peak of the literary mythos about St. Petersburg.

The Bronze Horseman, subtitled by the author “A Petersburg Tale,” is set during the flood of 1824, one of the worst of many that has regularly befallen the city. But the poem begins with a grand and solemn ode honoring Peter the Great and the city he founded, “the beauty and marvel” of the north. Then Pushkin warns, “Sorrowful will be my tale,” though previously he had treated the flood of 1824 frivolously, noting in a letter to his younger brother, Lev, “Voilà une belle occasion à vos dames de faire bidet.” {10} 10 3 Ibid., p. 109.

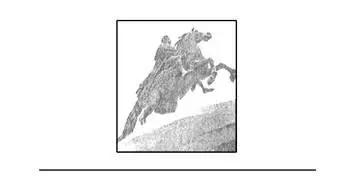

Then there is a sharp change in the protagonist, point of view, and mood. From Peter the Great and the early eighteenth century the action of Pushkin’s poem jumps to his contemporary Petersburg, where the poor clerk Yevgeny dreams of happiness with his beloved Parasha. A storm begins and rages into a flood. Caught in the center of the city, in Senate Square, Yevgeny saves himself by climbing onto a marble lion. Before him, towering above the “outraged Neva,” is the statue of Peter, “an idol on a bronze steed,” the Bronze Horseman himself.

The waves that cannot reach Peter, “the powerful master of fate,” who had founded the city in such a dangerous location, threaten to engulf Yevgeny. But he is more worried about the fate of his Parasha. The storm recedes and Yevgeny hurries to her little house. Alas, the house has been washed away and Parasha is missing. Her death is unbearable to Yevgeny, who loses his mind and becomes one of Petersburg’s homeless, living on handouts.

It is a plot typical of many a romantic tale. If Pushkin had ended it there, The Bronze Horseman, imbued with resounding verse that is at once ecstatic and precise—to date no translation has fully captured its brilliance—would not have risen to the philosophical heights at which it still serves as the most powerful expression of the ambiguity and eternal mystery of St. Petersburg’s mythos.

No, the culmination of this “Petersburg Tale” is still ahead. Pushkin brings his hero back to Senate Square. Yevengy once again faces the bronze “idol with outstretched hand / The one, whose fatal will founded the city beneath the sea.” So Peter the Great is at fault for Parasha’s death. And Yevgeny threatens the “miracle-working builder.” But the madman’s attempted rebellion against the statue of the absolute monarch on his rearing steed is short-lived. Yevgeny runs away imagining that the Bronze Horseman has come down from his pedestal to pursue him. No matter where the panicked Yevgeny turns, the cruel statue keeps gaining on him, and the terrible chase continues through the night under the pale Petersburg moon.

Thereafter, ever since that night, whenever Yevgeny makes his way through Senate Square, he proceeds cautiously; he dares not look up at the triumphant Bronze Horseman. In imperial Petersburg no one may rise up against even a statue of the monarch; that would be blasphemy. The life of the now completely humiliated Yevgeny has lost all meaning. In his wanderings he comes across Parasha’s ruined little house, washed up on a small island, and he dies on its doorstep.

This brief retelling of the comparatively short poem (481 octosyllabic lines) might create the impression that Pushkin’s sympathies are fully with poor Yevgeny, who became the prototype for an endless line of “little people” in Russian literature. But then the mystery of The Bronze Horseman would not have puzzled Slavic scholars the world over for the last one hundred fifty years and given rise to the hundreds of works approaching it from literary, philosophical, historical, sociological, and political points of view.

The mystery lies in the fact that while the reader’s first emotion is acute pity for the poor Petersburger, the perception of the poem does not end with that; new emotions and sensations wash over the reader. Gradually one understands that the author’s position is much more complex than it might at first have seemed.

The Bronze Horseman in Pushkin’s poem obviously represents not only Peter the Great and the city he founded but also the state itself and just about any form of authority—and, even more broadly, the creative will and force, upon which the society depends, but which also clash inevitably with the simple dreams and desires of its members, the insignificant Yevgenys and Parashas. What is more important—the individual’s fate or the city’s and the state’s triumph? It is Pushkin’s genius that he does not present a clear-cut answer. In fact, the text of his poem is open to opposing interpretations and so compels each reader to resolve its moral dilemma anew.

Читать дальше