‘The thousands of marriages

Lasting a little while longer. .’

Like the Newfoundland Memorial, the other major Canadian memorial, at Vimy Ridge, is located in an expanse of parkland in which the original trenches have been neatly maintained. A road winds up to the park through thick woods. Then, suddenly, the monument looms into view: two white pylons, each with a sculpted figure perched precariously near the top. Sunlight knifes through the clouds.

Twin white paths stretch across the grass. The steps to the monument are flanked by two figures, a naked man and a naked woman. The stone is dazzling white. It is difficult to estimate the height of the pylons. A hundred feet? Two hundred? Impossible to say: there is nothing around to stand comparison with the monument. It generates its own scale, dwarfing the idea of measurement. At its base, between the two pylons, is a group of figures thrusting a torch upwards towards the figures perched high above. The distance between them is measureless.

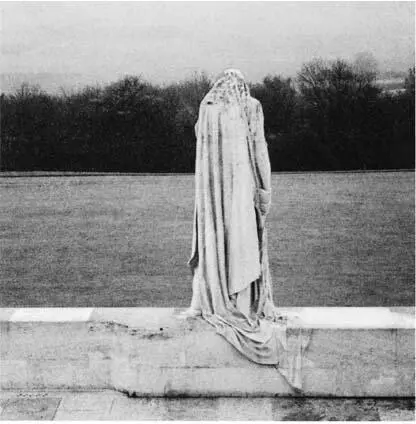

Carved on the walls are the names of Canada’s missing: 11,285 men with no known graves. I walk round to the east side of the monument where a group of figures are breaking a sword. Far off, in the other corner, is another similar group whose details I cannot make out at this distance. Between them, brooding over a vast sea of grass, is the shrouded form of a woman, her stone robes flowing over the ground. The figure spans millennia of grieving women, from pietàs showing the weeping Virgin to photos of widowed peasant women wrapped in shawls against the cold. Below her, resting on a tomb, are a sword and steel helmet, the shadows of the twin pylons stretching out across the grass.

Vimy Ridge: the Canadian war memorial

The Memorial took eleven years to construct. Unveiled, finally, in 1936, it was the last of the great war memorials to be completed. Walter Allward, the sculptor and designer, explained its symbolism in the following terms. The grieving woman represents Canada, a young nation mourning her dead; the figures to her left show the sympathy of Canada for the helpless; to her right the Defenders are breaking the sword of war. Between the pillars, Sacrifice throws the torch to his comrades; high up on the pylons are allegorical figures of Honour, Faith, Justice, Hope, Peace. . This string of virtues recalls a speech made by Lloyd George in September 1914 in which he itemized

Grief. .

the great everlasting things that matter for a nation — the great peaks we had forgotten, of Honour, Duty, Patriotism and, clad in glittering white, the great pinnacle of Sacrifice pointing like a rugged finger to Heaven.

In its glittering whiteness Allward’s monument seems the shorn embodiment of Lloyd George’s words. Duty and Patriotism have fallen away; Honour takes its place alongside Hope and peace as allegorical decoration; Sacrifice remains undiminished: unmeasurable, sheer — but its meaning, too, has been transformed by the war. It is here confronted with the consequence of its meaning.

Discounting the allegorical ‘Defenders’ there are no military figures on the monument. The steel helmet on the tomb is the only clear symbolic link with the war it commemorates. The figures at the base of the pylons strain upward, straining to rise above their grief, to surmount it until, like the figures nestling in the sky above them, they can overcome it. This vertiginous transcendence is counterpoised by the earthward gaze of the woman. Mute with sorrow she makes no appeal to the heavens but fixes her eyes on the ground, making an accommodation with grief, residing in loss.

Owen, wrote C. Day Lewis, ‘had no pity to spare for the suffering of bereaved women’. Vimy Ridge, by contrast, seems less a memorial to the dead, to the abstract ideal of Sacrifice, than to the reality of grief: a memorial not to the Unknown Soldier but to Unknown Mothers.

I remember reading of a soldier’s visit to the mother of a dead friend: ‘“I’ve lost my only boy,” was all she said, then became mute with grief.’

And then, as sometimes happens, this word ‘grief’ that I have used many times floats free of meaning and becomes a sound, an abstract arrangement of letters whose sense is suddenly lost. Grief, grief, grief. I say the word to myself until, gradually, it is reunited with the meaning it has always had.

I was living in New Orleans when the Gulf War ended. The city was swathed in yellow ribbons and each night I watched news reports about soldiers returning home to their loved ones, their sweethearts. Hugs and tears, brass bands playing, kisses, babies born while their fathers were away in the desert of Kuwait.

But what about the soldier with no girlfriend, no wife, no sweetheart to return to? The loner. Returning to nothing, surrounded by tickertape reunions, reminding me of a photograph from the Great War there was no one around to take.

Sepia weather. Shouldering his kit, making for the railway station. Heading home through force of habit. Holding his peace, coughing. The sky sagging over damp shires. The names of stations. Dead men’s faces. Rain falling on smoke-stained towns. From now on this is what life will be: staring through a rain-grimed window, waiting for the journey to be over with. Houses and brooks passing by. Fields of wet nettles.

* * *

From the car, glancing back, the sculptures clinging to the sides of the two pylons give them the look of war-ravaged trees: blasted white trunks from which the stumps of branches protrude.

‘ The charred skeletons of the trees’

Barbusse’s terse entry in his War Diary is echoed, repeated or expanded upon in almost every account of the war. Harold Macmillan thought ‘the most extraordinary thing about the modern battlefield is the desolation and emptiness of it all. Nothing is to be seen of war or soldiers — only the split and shattered trees.’ Writing to Ezra Pound in June 1917, Wyndham Lewis noted that ‘shells never seem to do more than shave the trees down to these ultimate black stakes. .’

Trees were not the only things to display the resilience of the vertical. There were remains of buildings like ‘the famous Cloth Hall looking stark and naked with one wall standing’ in the centre of Ypres. Or there were the ubiquitous calvaries (‘One ever hangs where shelled roads part’), the most famous of which, again in Ypres, in the cemetery, remained miraculously intact after a dud shell lodged between the cross and the figure of the suffering Christ. As often as not these roadside crucifixes were sinister and troubling reminders of mortality rather than images of redemption. Having endured a long, terrifying wait on. ‘Mount Calvary’ — the Germans can all the time be heard mining beneath them — the squad in Raymond Dorgeles’ Wooden Crosses is finally relieved. As they march quickly away, leaving other men to take their place on the powder keg, Dorgeles looks back: ‘The Calvary stood out terrible, a dreadful thing against the green night, with its battered stumps of trees like the uprights of a cross.’ A history of the Gloucesters recalls that

‘Totenlandschaft’

The cemetery at Richebourg was an eerie spot; it had been completely churned up by shell-fire: tombs torn open to reveal skeletons that had lain there for years. The crucifix, as was so often the case, remained standing.

Читать дальше