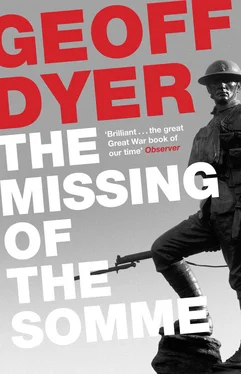

Geoff Dyer - The Missing of the Somme

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Geoff Dyer - The Missing of the Somme» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2012, Издательство: Canongate Books, Жанр: Биографии и Мемуары, Публицистика, Критика, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Missing of the Somme

- Автор:

- Издательство:Canongate Books

- Жанр:

- Год:2012

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Missing of the Somme: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Missing of the Somme»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Missing of the Somme — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Missing of the Somme», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

This tone of deadpan resignation is surprisingly versatile. It embraces a range of the rhetorical devices catalogued in The Great War and Modern Memory . Fussell notes the way that The Pilgrim’s Progress provided a symbolic map of the war (Passchendaele is the Slough of Despond); one of Macdonald’s interviewees begins with the graphically exact understatement, ‘The salient was a dead loss,’ and moves in ten lines beyond Bunyan to describe it as ‘just a complete abomination of desolation’.

This pretty much sums up our feelings about Passchendaele. We buy bread, fruit and pink-coloured meat at a supermarket and then go for coffee. At eleven-thirty in the morning the café is already full of men, beer and smoke.

‘To our dismay, on counting our money, we found that it was nearly gone,’ noted Williamson in 1927. ‘Whither had it gone?’

‘We must have spent more on beer than we thought,’ suggests Paul before going through the figures in the back of his notebook again. However we look at it, money is pouring through our fingers. After further anguished calculations we put it down to the exchange rate. A few weeks ago the pound plunged to a new record low, and as a consequence we are sitting here in Passchendaele, the poor men of Europe, licking our financial wounds.

We leave the café and head for Tyne Cot Cemetery, a vast, sprawling city of the dead. Like any metropolis it has preserved the haphazard, unregulated heart of the old city: the 300 or so graves that were found here after the armistice. Since then it has spread out in a series of radial fans and neat purpose-built suburban blocks, accommodating over eleven thousand of the dead of the rural battlefields. Even rough-hewn German bunkers were absorbed by the city’s irenic expansion.

Rain has cratered and pocked the earth around the headstones, smeared them with mud. The grass has been worn bare in places. The sky is grey with cold. Flowers have been pruned back to their stems. It is easy to imagine that the shedding of leaves is only the first stage in nature’s cutting back for winter. In time branches will shrink back into trunks and trunks into earth until only frost-ravaged headstones remain above the ground.

It is so cold that we stay only a short time before Paul says,

‘Let’s get back in the car.’

‘Tank, Paul, tank.’

‘Sorry. “Tank.”’

‘And say “sir” when you say “tank”.’

‘Tank, sir. Yes, sir.’

Our next stop is the Hill 60 Museum, which for the rest of the trip we refer to as the Little Shop of Horrors. If Hill 60 seemed out of place in that list of sinister names — a stray from Vietnam — this place soon persuades you of its right to be included among them. Out front is a ‘theme’ café decorated with wartime bric-à-brac. One of those creepy old war songs is playing on a scratchy gramophone: ‘It’s a long way to Tipperary. .’ The canned past.

The first room of the museum proper is given over mainly to stereoscopic viewers. Bright sepia in 3-D: lines of blasted trees receding into history; an exaggerated perspective on the past. Everything is covered in dust, ‘the flesh of time’ Brodsky calls it, ‘time’s very flesh and blood’. The walls are lined with photographs, photographs of the muddy dead. Another trench song, ‘The Old Battalion’, scratches and crackles through the speakers:

If you want to find the old battalion,

I know where they are:

They’re hanging on the old barbed wire.

I’ve seen ’em, I’ve seen ’em,

Hanging on the old barbed wire.

The next room is given over to hideous uniforms and a random assortment of broken bayonets, revolvers and shell casings. There are a couple of petrified boots, the remains of a rifle so rusty it looks like it has been salvaged from a coral reef. A dusty damp smell — damp rot, rotting dust — pervades the place. It is as if Steptoe and Son have opened up their own branch of the Imperial War Museum.

Through a glass door we step out into the rain-clogged trenches and ditches. Everything here is rusty. Not just the strips of corrugated iron which, let’s face it, were designed to rust, but the earth and leaves. The year is turning to rust. Mud is old rust with dirt mixed in. Water is liquid rust.

By now the tank is a slum. It is littered with pâté rind, bread crumbs, greaseproof paper, orange peel and banana skins. Tins of beer rattle across the floor every time we turn a corner. From the outside hardly a square inch of the original paintwork can be seen. Even the interior is caked with mud from our boots.

Paul is driving. We are waiting at a junction. He begins pulling out on to the main road.

‘Watch out!’

A truck, overtaking a car on the main road, thunders past, missing us by inches. We’re all stunned. We talk about nothing else for the next hour.

‘Think of the publicity that would have got for your book,’ says Mark. ‘Getting killed before you even wrote it.’

‘This is not a book about Paul’s driving,’ I say. ‘English poetry is not yet fit to speak of it.’

‘Dulce et decorum est in tankus mori,’ says Paul.

Messines Ridge Cemetery is set back from the road, in the middle of a quiet wood. The graves are strewn with leaves: yellow, flecked with black, brown-green. At the back of the cemetery is an arcade of classical pillars. Even the slightest breeze is enough to tug leaves from the trees. The rustle of a pheasant breaking free of the silence. Rain dripping through trees. Damp bird calls.

The headstones are turning green with moss. The words ‘Their Glory Shall Not Be Blotted Out’ are blotted out by mud splashed up by rain.

As each year passes, it grows more difficult to keep time at bay. A quarter of a century’s moss forms in one year. Time is trying to make up for lost time. Left untended this cemetery, with its classical pillars, would look like an ancient ruin in a couple of years. If the machine-gun’s unprecedented destructive power made it ‘concentrated essence of infantry’, then here we have concentrated essence of the past. This is the look the past tends towards.

We come to the vast German cemetery at Langemark. A pile of horse dung lies, accidentally, I suppose, in the entrance. Nearly 25,000 men are buried here in a mass grave. At the edge of the Kameradengrab stand four mourning figures, silhouetted against the zinc sky. Up close these are poorly sculpted figures, but from a distance they impart a sense of utter desolation to the place. It is as if the minute’s silence for which they have bowed their heads has been extended for the duration of eternity. Names are printed on low grey pillars. To the right there are individual graves marked by flat slabs of stone.

There is no colour here, no flowers, nothing transcendent. The dead as individuals hardly matter; only as elements of the nation. There are no individual inscriptions, no rhetoric. Only the unadorned facts of mortality — and even these are reduced to a bare, bleak minimum. This is the meaning and consequence of defeat.

The French cemetery at Notre Dame de Lorette covers twenty-six acres. There are 20,000 named graves here; in the ossuary lie the remains of another 20,000 unknown dead. It is icy cold. Wind streams across the grey hill. Wind is not something that passes through the sky. The sky is wind and nothing else. Crosses stretch away in lines so long they seem to follow the curvature of the earth. Names are written on both the front and back of each cross. The scale of the cemetery exceeds all imagining. Even the names on the crosses count for nothing. Only the numbers count, the scale of loss. But this is so huge that it is consumed by itself. It shocks, stuns, numbs. Sassoon’s nameless names here become the numberless numbers. You stand aghast while the wind hurtles through your clothes, searing your ears until you find yourself almost vanishing: in the face of this wind, in this expanse of lifelessness, you cannot hold your own: you do not count. There is no room here for the living. The wind, the cold, force you away.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Missing of the Somme»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Missing of the Somme» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Missing of the Somme» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.