And yet the Las Vegas wedding business seems to appeal to precisely that impulse. “Sincere and Dignified Since 1954,” one wedding chapel advertises. There are nineteen such wedding chapels in Las Vegas, intensely competitive, each offering better, faster, and, by implication, more sincere services than the next: Our Photos Best Anywhere, Your Wedding on A Phonograph Record, Candlelight with Your Ceremony, Honeymoon Accommodations, Free Transportation from Your Motel to Courthouse to Chapel and Return to Motel, Religious or Civil Ceremonies, Dressing Rooms, Howers, Rings, Announcements, Witnesses Available, and Ample Parking. All of these services, like most others in Las Vegas (sauna baths, payroll-check cashing, chinchilla coats for sale or rent) are offered twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week, presumably on the premise that marriage, like craps, is a game to be played when the table seems hot.

But what strikes one most about the Strip chapels, with their wishing wells and stained-glass paper windows and their artificial bouvardia, is that so much of their business is by no means a matter of simple convenience, of late-night liaisons between show girls and baby Crosbys. Of course there is some of that. (One night about eleven o’clock in Las Vegas I watched a bride in an orange minidress and masses of flame-colored hair stumble from a Strip chapel on the arm of her bridegroom, who looked the part of the expendable nephew in movies like Miami Syndicate. “I gotta get the kids,” the bride whimpered. “I gotta pick up the sitter, I gotta get to the midnight show.” “What you gotta get,” the bridegroom said, opening the door of a Cadillac Coupe deVille and watching her crumple on the seat, “is sober”) But Las Vegas seems to offer something other than “convenience”; it is merchandising “nice-ness,” the facsimile of proper ritual, to children who do not know how else to find it, how to make the arrangements, how to do it “right.” All day and evening long on the Strip, one sees actual wedding parties, waiting under the harsh Ughts at a crosswalk, standing uneasily in the parking lot of the Frontier while the photographer hired by The Little Church of the West (“Wedding Place of the Stars”) certifies the occasion, takes the picture: the bride in a veil and white satin pumps, the bridegroom usually in a white dinner jacket, and even an attendant or two, a sister or a best friend in hot-pink peau de soie, a flirtation veil, a carnation nosegay. “When I Fall in Love It Will Be Forever,” the organist plays, and then a few bars of Lohengrin. The mother cries; the stepfather, awkward in his role, invites the chapel hostess to join them for a drink at the Sands. The hostess declines with a professional smile; she has already transferred her interest to the group waiting outside. One bride out, another in, and again the sign goes up on the chapel door: “One moment please — Wedding.”

I sat next to one such wedding party in a Strip restaurant the last time I was in LasVegas. The marriage had just taken place; the bride still wore her dress, the mother her corsage. A bored waiter poured out a few swallows of pink champagne (“on the house”) for everyone but the bride, who was too young to be served. “You’ll need something with more kick than that,” the bride’s father said with heavy jocularity to his new son-in-law; the ritual jokes about the wedding night had a certain Panglossian character, since the bride was clearly several months pregnant. Another round of pink champagne, this time not on the house, and the bride began to cry. “It was just as nice,” she sobbed, “as I hoped and dreamed it would be.”

1967

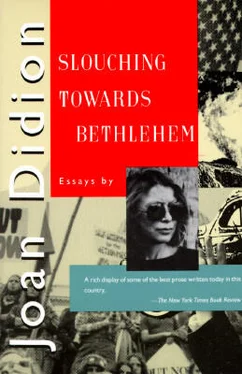

Slouching Towards Bethlehem

the center was not holding. It was a country of bankruptcy notices and public-auction announcements and commonplace reports of casual killings and misplaced children and abandoned homes and vandals who misplaced even the four-letter words they scrawled. It was a country in which families routinely disappeared, trailing bad checks and repossession papers. Adolescents drifted from city to torn city, sloughing off both the past and the future as snakes shed their skins, children who were never taught and would never now learn the games that had held the society together. People were missing. Children were missing. Parents were missing. Those left behind filed desultory missing-persons reports, then moved on themselves.

It was not a country in open revolution. It was not a country under enemy siege. It was the United States of America in the cold late spring of 1967, and the market was steady and the G. N. P high and a great many articulate people seemed to have a sense of high social purpose and it might have been a spring of brave hopes and national promise, but it was not, and more and more people had the uneasy apprehension that it was not. All that seemed clear was that at some point we had aborted ourselves and butchered the job, and because nothing else seemed so relevant I decided to go to San Francisco. San Francisco was where the social hemorrhaging was showing up. San Francisco was where the missing children were gathering and calling themselves “hippies.” When I first went to San Francisco in that cold late spring of 1967 I did not even know what I wanted to find out, and so I just stayed around awhile, and made a few friends.

A sign on Haight Street, San Francisco:

Last Easter Day

My Christopher Robin wandered away.

He called April 10th

But he hasn’t called since

He said he was coming home

But he hasn’t shown.

If you see him on Haight

Please tell him not to wait

I need him now

I don’t care how

If he needs the bread

I’ll send it ahead.

If there’s hope

Please write me a note

If he’s still there

Tell him how much I care

Where he’s at I need to know

For I really love him so!

Deeply,

Maria

Maria Pence

12702 N.E. Multnomah

Portland, Ore. 97230

503 /252-2720.

I am looking for somebody called Deadeye and I hear he is on the Street this afternoon doing a little business, so I keep an eye out for him and pretend to read the signs in the Psychedelic Shop on Haight Street when a kid, sixteen, seventeen, comes in and sits on the floor beside me.

“What are you looking for,” he says.

I say nothing much.

“I been out of my mind for three days,” he says. He tells me he’s been shooting crystal, which I already pretty much know because he does not bother to keep his sleeves rolled down over the needle tracks. He came up from Los Angeles some number of weeks ago, he doesn’t remember what number, and now he’ll take off for New York, if he can find a ride. I show him a sign offering a ride to Chicago. He wonders where Chicago is. I ask where he comes from. “Here,” he says. I mean before here. “San Jose, Chula Vista, I dunno. My mother’s in Chula Vista.”

A few days later I run into him in Golden Gate Park when the Grateful Dead are playing. I ask if he found a ride to New York. “I hear New York’s a bummer,” he says.

Deadeye never showed up that day on the Street, and somebody says maybe I can find him at his place. It is three o’clock and Deadeye is in bed. Somebody else is asleep on the living-room couch, and a girl is sleeping on the floor beneath a poster of Allen Ginsberg, and there are a couple of girls in pajamas making instant coffee. One of the girls introduces me to the friend on the couch, who extends one arm but does not get up because he is naked. Deadeye and I have a mutual acquaintance, but he does not mention his name in front of the others. “The man you talked to,” he says, or “that man I was referring to earlier.” The man is a cop.

Читать дальше