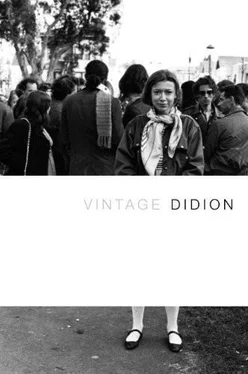

Joan Didion - Vintage Didion

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Joan Didion - Vintage Didion» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2004, Издательство: Vintage Books, Жанр: Биографии и Мемуары, Публицистика, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Vintage Didion

- Автор:

- Издательство:Vintage Books

- Жанр:

- Год:2004

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Vintage Didion: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Vintage Didion»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Vintage Didion — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Vintage Didion», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

To be a man of action in Miami was to receive encouragement from many quarters. On the wall of the reception room at WRHC–Cadena Azul, Miami, where the sales manager was Guillermo Novo and an occasional commentator was Fidel and Raúl Castro’s estranged sister Juanita and the host of the most popular talk show was Felipe Rivero, whose family had from 1832 until 1960 published the powerful Diario de la Marina in Havana and who would in 1986, after a controversy fueled by his insistence that the Holocaust had not occurred but had been fabricated “to defame and divide the German people,” move from WRHC to WOCN, there hung in 1985 a framed letter, the letter Guillermo Novo had mentioned when he first materialized that Monday morning. This letter, which was dated October 1983 and signed by the president of the United States, read:

I learned from Becky Dunlop [presumably Becky Norton Dunlop, a White House aide who later followed Edwin Meese to the Justice Department] about the outstanding work being done at WRHC. Many of your listeners have also been in touch, praising your news coverage and your editorials. Your talented staff deserves special commendation for keeping your listeners well-informed.

I’ve been particularly pleased, of course, that you have been translating and airing a Spanish version of my weekly talks. This is important because your signal reaches the people of Cuba, whose rigidly controlled government media suppress any news Castro and his communist henchmen do not want them to know. WRHC is performing a great service for all its listeners. Keep up the good work, and God bless you.

[signed] R

ONALD

R

EAGAN

At the time I first noticed it on the WRHC wall, and attracted Guillermo Novo’s attention by reading it, this letter interested me because I had the week before been looking back through the administration’s arguments for Radio Martí, none of which, built as they were on the figure of beaming light into utter darkness, had alluded to these weekly talks that the people of Cuba appeared to be getting on WRHC–Cadena Azul, Miami. Later the letter interested me because I had begun reading back through the weekly radio talks themselves, and had come across one from 1978 in which Ronald Reagan, not yet president, had expressed his doubt that either the Pinochet government or the indicted “Cuban anti-Castro exiles,” one of whom had been Guillermo Novo, had anything to do with the Letelier assassination.

Ronald Reagan had wondered instead (“I don’t know the answer, but it is a question worth asking….”) if Orlando Letelier’s “connections with Marxists and far-left causes” might not have set him up for assassination, caused him to be, as the script for this talk put it, “murdered by his own masters.” Here was the scenario: “Alive,” Ronald Reagan had reasoned in 1978, Orlando Letelier “could be compromised; dead he could become a martyr. And the left didn’t lose a minute in making him one.” Actually this version of the Letelier assassination had first been advanced by Senator Jesse Helms (R-N.C.), who had advised his colleagues on the Senate floor that it was not “plausible” to suspect the Pinochet government in the Letelier case, because terrorism was “most often an organized tool of the left,” but the Reagan reworking was interesting on its own, a way of speaking, later to become familiar, in which events could be revised as they happened into illustrations of ideology.

“There was no blacklist of Hollywood,” Ronald Reagan told Robert Scheer of the Los Angeles Times during the 1980 campaign. “The blacklist in Hollywood, if there was one, was provided by the communists.” “I’m going to voice a suspicion now that I’ve never said aloud before,” Ronald Reagan told thirty-six high-school students in Washington in 1983 about death squads in El Salvador. “I wonder if all of this is right wing, or if those guerrilla forces have not realized that by infiltrating into the city of San Salvador and places like that, they can get away with these violent acts, helping to try and bring down the government, and the right wing will be blamed for it.” “New intelligence shows,” Ronald Reagan told his Saturday radio listeners in March of 1986, by way of explaining why he was asking Congress to provide “the Nicaraguan freedom fighters” with what he called “the means to fight back,” that “Tomás Borge, the communist interior minister, is engaging in a brutal campaign to bring the freedom fighters into discredit. You see, Borge’s communist operatives dress in freedom fighter uniforms, go into the countryside and murder and mutilate ordinary Nicaraguans.”

Such stories were what David Gergen, when he was the White House communications director, had once called “a folk art,” the President’s way of “trying to tell us how society works.” Other members of the White House staff had characterized these stories as the President’s “notions,” casting them in the genial framework of random avuncular musings, but they were something more than that. In the first place they were never random, but systematic and rather energetically so. The stories were told to a single point. The language in which the stories were told was not that of political argument but of advertising (“New intelligence shows…” and “Now it has been learned …” and, a construction that got my attention in a 1984 address to the National Religious Broadcasters, “Medical science doctors confirm …”), of the sales pitch.

This was not just a vulgarity of diction. When someone speaks of Orlando Letelier as “murdered by his own masters,” or of the WRHC signal reaching a people denied information by “Castro and his communist henchmen,” or of the “freedom fighter uniforms” in which the “communist operatives” of the “communist interior minister” disguise themselves, that person is not arguing a case, but counting instead on the willingness of the listener to enter what Hannah Arendt called, in a discussion of propaganda, “the gruesome quiet of an entirely imaginary world.” On the morning I met Guillermo Novo in the reception room at WRHC–Cadena Azul I copied the framed commendation from the White House into my notebook, and later typed it out and pinned it to my own office wall, an aide-mémoire to the distance between what is said in the high ether of Washington, which is about the making of those gestures and the sending of those messages and the drafting of those positions that will serve to maintain that imaginary world, about two-track strategies and alternative avenues and Special Groups (Augmented), about “not breaking faith” and “making it clear,” and what is heard on the ground in Miami, which is about consequences.

In many ways Miami remains our most graphic lesson in consequences. “I can assure you that this flag will be returned to this brigade in a free Havana,” John F. Kennedy said to the surviving members of the 2506 Brigade at the Orange Bowl in 1962 (the “supposed promise,” the promise “not in the script,” the promise “made in the emotion of the day”), meaning it as an abstraction, the rhetorical expression of a collective wish; a kind of poetry, which of course makes nothing happen. “We will not permit the Soviets and their henchmen in Havana to deprive others of their freedom,” Ronald Reagan said at the Dade County Auditorium in 1983 (2,500 people inside, 60,000 outside, 12 standing ovations and a pollo asado lunch at La Esquina de Tejas with Jorge Mas Canosa and 203 other provisional loyalists), and then Ronald Reagan, the first American president since John F. Kennedy to visit Miami in search of Cuban support, added this: “Someday, Cuba itself will be free.”

This was of course just more poetry, another rhetorical expression of the same collective wish, but Ronald Reagan, like John F Kennedy before him, was speaking here to people whose historical experience has not been that poetry makes nothing happen. On one of the first evenings I spent in Miami I sat at midnight over came con papas in an art-filled condominium in one of the Arquitectonica buildings on Brickell Avenue and listened to several exiles talk about the relationship of what was said in Washington to what was done in Miami. These exiles were all well-educated. They were well-read, well-traveled, comfortable citizens of a larger world than that of either Miami or Washington, with well-cut blazers and French dresses and interests in New York and Madrid and Mexico. Yet what was said that evening in the expensive condominium overlooking Biscayne Bay proceeded from an almost primitive helplessness, a regressive fury at having been, as these exiles saw it, repeatedly used and repeatedly betrayed by the government of the United States. “Let me tell you something,” one of them said. “They talk about ‘Cuban terrorists.’ The guys they call ‘Cuban terrorists’ are the guys they trained.”

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Vintage Didion»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Vintage Didion» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Vintage Didion» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.