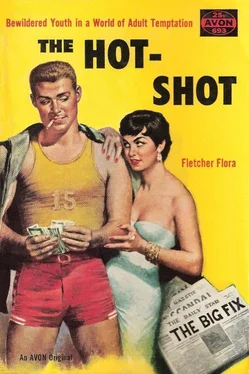

I had fifteen lousy cents in my pocket, and I wondered what the hell I’d do if Marsha wanted to stop somewhere for a coke or something, and I was thinking that maybe I could get away with that old dodge of putting your hand in your pocket and feeling around and saying, “Well, Jesus Christ, what could’ve happened to the money I had? Do you suppose I could’ve left it in my other pants?” but just then who do you think I saw but old Bugs dropping a nickel in a pin ball machine at the end of the soda fountain. There was an outside chance that Bugs might have some dough, even if it was a damn slim one, so I went up to him and said, “Hi, Bugs, old boy. You happen to have an extra buck on you?” and to tell the truth, I never had any God-damn idea he had anything like that much, if any at all except the nickel he’d just dropped in the machine, but I could tell right away by the sneaky look that got on his face that he really had it.

“Hi, Skimmer,” he said. “Where the hell would I get that kind of dough?”

“Same place you always get it,” I said. “Out of your grandmother’s purse.”

It was a pretty good shot, and it was plain enough from the way old Bugs got all red in the face that I’d hit it right on the nose. Old Bugs had this grandmother who was about a million years old and got a pension from the government because Bugs’s grandfather had been in some God-damn war back in the Middle Ages or sometime. Every month after she got her pension, she’d put part of it in the bank and put the rest of it in this little black purse she carried around with her. The way she carried the purse, she’d wrap it in a handkerchief and pin it to her long underwear under about six inches of other underclothes and stuff, and the only way Bugs could get to it was to wait until she’d undressed and gone to bed. She kept pieces of hoarhound candy in the purse with the money, and you could always tell when old Bugs had swiped some money from his grandmother because it always smelled like this God-damn hoarhound.

Well, he swore up and down that he didn’t have any, but I knew he was a damn liar and just didn’t want to come across for a buddy, so I said, “Look, Bugs, don’t give me any crap now, because I’ve got to have some lousy dough, and I’ll tell you why. I got this date with Marsha Davis, and I’m stony, and she’s going to be here any minute to pick me up in her old man’s car.”

He looked at me and said, “Oh, bull, you haven’t any more got a date with Marsha Davis than I have,” and I said, “The hell I haven’t. You just stand up inside the window and see if she doesn’t pick me up, and if you’ll let me have a buck I’ll tell you what I’ll do. I’ll try to fix you up with one of Marsha’s friends.”

That was a God-damn laugh, because no classy doll was going to have any time for old Bugs, even if he’d played on a dozen lousy basketball teams, and besides he was only a stinking substitute who hardly ever got to play in a real game, but it worked just the same, Bugs being pretty God-damn stupid when you got right down to it, and he said, “No bull, Skimmer? You really think you could fix me up?”

I said sure, it was a cinch, and he forked over a buck, and sure enough, it smelled just like this stinking hoarhound. I took the money and started for the door, and Bugs followed me up past the soda fountain saying, “Don’t forget now, Skimmer. You promised to fix me up,” and I said, “Sure, sure, I’ll fix it, Bugs,” even though I didn’t really have any idea of doing any such damn thing, and I went on outside and stood by the curb and waited. It was quite a while before she got there, and I began to think how maybe she wasn’t coming after all, and how old Bugs would hoot if she didn’t, and how I’d knock his God-damn teeth out if he did, and that’s for damn sure the trouble with having a classy doll like Marsha on the string, she always keeps your lousy guts in an uproar. Pretty soon she came, though, in this black Buick about a mile long. She pulled up to the curb and said, “Hop in, Skimmer,” and I hopped in beside her and looked back through the window of the drug store, and there was old Bugs with his teeth hanging out, and I could see that he was just about to wet his drawers, he was so God-damn jealous.

We went buzzing along in this big Buick that was like riding on the damn air, it took the bumps in the crummy street so easy, and Marsha said, “Sorry I was so long picking you up, Skimmer, but Dad always has to go through this deadly routine of giving me simply hours of instructions when I take the car out, and it’s just too sickening for words.” and I said, “I was just fooling around killing time anyhow. Would you like to go over to Tompkins’ for something?” and she said, “No, I don’t think I’d better go to Tompkins’, because I’m supposed to be over at Marion’s, and if I went to Tompkins’, Dad would be sure to hear of it. Honestly, I think that man has paid spies or something, and besides I only have the car for an hour, instead of two hours like I thought, and I know we can find something better to do than sit around in Tompkins’ with a lot of juveniles. Honestly, Skimmer, don’t you sometimes find them just too juvenile?”

I said I sure as hell did, and by that time we’d got out to the edge of town, not on a highway but on a little farm-to-market road, and she said, “What are you sitting way over on that side of the seat for, Skimmer?” Well, I may be a little slow on the uptake sometimes, but I don’t have to be kicked in the teeth before I get the God-damn point, so I eased across the seat until I was right up against her, and she said, “You wouldn’t bother me if you put your arm around me,” so I did.

We kept on going out the gravel road until we got to the river, and we kept talking about how she’d missed me, and I’d missed her, and how the past week had been longer than a damn year, and how strange it was how something had just gone bang like a God-damn bomb the minute we first looked at each other, and when we got to the river she turned off at the end of the bridge onto another little road that went along the bank down past some cabins. Pretty soon we came to one that was bigger than the rest, set in under some trees, and she stopped the Buick beside the cabin and said, “This is the old man’s shack, in case you’re interested. He comes out here fishing in the summers, and sometimes he brings his friends out here when they want to have a brawl that might corrupt their dear children if they had it at home. Isn’t it just too disgusting how transparent fathers are?” I said sure, fathers were for the book, and I could have backed that up with some stories about my old man that would probably have made her think hers was practically a plaster saint or something, but I didn’t and she slipped out of the seat on her side and said, “Let’s walk down and look at the river.”

We walked down to the bank and looked at the river going past, and she said, “There’s something about a river that makes you feel kind of sad, isn’t there?” and I said it made me feel that way too, which was a lie, and to tell the truth, it wasn’t much of a river, and just a lot of God-damn muddy water as far as I could see. We kissed once while we were standing there, but it was too damn cold with the wind blowing at us across the river, and so we went back to the Buick and really got started. Man, we really wallowed all over the lousy seat, and I won’t tell you what all we did, any details or anything like that, but it’ll give you an idea when you hear what she finally said. She laughed this little laugh and said, “Tough luck, Skimmer. I’m in the saddle.”

To tell the truth, it sort of got me for a minute, hearing her come right out with it like that, just as cool as a Goddamn cucumber, because girls usually act like it was a stinking crime or something and will go all out to keep a guy from finding out anything like that ever happens, and once I razzed old Mopsy about it a little, and she got all colors and began to bawl like I’d accused her of being queer at least. Anyhow, that put a ceiling on us, but we kept fooling around a long time under the ceiling, and she kept whispering things to me like how cute I was, and rugged, and sort of tough-like and different from all the other guys she knew, and then she sat up all of a sudden and looked at her wrist watch and said, “Oh, my God, my hour’s up, and we haven’t even started home. My father will simply be livid.”

Читать дальше