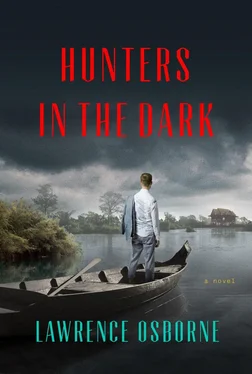

Lawrence Osborne - Hunters in the Dark

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Lawrence Osborne - Hunters in the Dark» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2016, Издательство: Hogarth, Жанр: Триллер, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Hunters in the Dark

- Автор:

- Издательство:Hogarth

- Жанр:

- Год:2016

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Hunters in the Dark: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Hunters in the Dark»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

compares to Paul Bowles, Evelyn Waugh and Ian McEwan, an evocative new work of literary suspense. Adrift in Cambodia and eager to side-step a life of quiet desperation as a small-town teacher, 28-year-old Englishman Robert Grieve decides to go missing. As he crosses the border from Thailand, he tests the threshold of a new future.

And on that first night, a small windfall precipitates a chain of events- involving a bag of “jinxed” money, a suave American, a trunk full of heroin, a hustler taxi driver, and a rich doctor’s daughter- that changes Robert’s life forever.

Hunters in the Dark

Hunters in the Dark — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Hunters in the Dark», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“It was the same guy from last night.”

She frowned and there was a sudden anxiety in her voice.

“Him?”

“Looked a bit rough to you?”

“He looked like a con man. I wouldn’t talk to him, no.”

“Not at all,” Robert protested. “He’s a riot. You should meet him.”

“I don’t want to meet him.”

“I’m sure he wants to meet you. He suggested taking us on a tour.”

“You said no, I hope?”

“Of course I said no. But he’s sort of funny. I quite like him.”

“Don’t even think about it!”

They went up to the room and made love. The heat of the day seeped through the flimsy curtains and made them feel washed out and spectral, but the thread of the conversation begun lightheartedly in the lobby was not broken and sure enough it resumed eventually.

“I said no to the tour, as I said. But all the same—”

She said, “What is he doing hanging out in the lobby like that? It doesn’t feel right.”

“He says he’s fishing for clients.”

She snorted. “That’s one thing to dislike.”

“Maybe. Maybe not.”

“Remember, you’re not local. You don’t pick up on these things.”

“What things?”

“The vibe. He looked at me—”

“He’s just a horny old man. I’m sure they all look at you like that. We can’t hold that against him, can we?”

“You think I want to be holed up in a car with that for hours on end?”

“I suppose not,” he admitted reluctantly.

Moreover, he was not sure why he wanted to go on that tour now. It just seemed like a fairly good idea for a romantic weekend, but more than that it was an added layer to his disguise, a distraction from the question which he now imagined was turning inside Sophal’s mind about his identity. The more normal things they did together, the less she might brood about Robert and his loose ends. This was how he was thinking, in any case, though it was more a blind probing than a train of thought. He thought it would be clever to kick up a little dust and commotion because of late he had begun to feel a quiet suspicion in her. It was her instinct cutting in and the only way to foil instinct is to spoil, entertain and divert. She lay now against his chest with her hand resting on the area of the heart and he could feel her aroused attentiveness and wariness. He was correct. Sophal had bristled at the mention of a tour in the east with a man like that and she began to wonder at once why he had suggested it. His breath still smelled of that cheap rum and it was obvious who he had been drinking with. Why, though, would a man like Simon sit down and drink rum with a man like the tour guide? What would they have to talk about?

How annoying men were, there was always this collusion which even they didn’t understand.

“You should be more careful,” she said quietly. “You shouldn’t talk to strangers so easily.”

“Why not?”

“You just shouldn’t. It’s quicksand.”

“Quicksand?”

“That’s what my father says. It’s quicksand for naive boys.”

“Oh, I’m not a naive boy.”

“You’re not as naive as you seem, but you’re more naive than you think. That’s what matters. If I can see that, so can Mr. Tour Guide.”

“Come off it,” he sighed, smiling to himself. “It’s not that easy. I’m not that easy.”

“You’re wrong — it’s that easy. You should stay away from him.”

“Bollocks,” he muttered.

She didn’t quite get Britishisms.

There’s a long road that goes east to Vietnam and at the end is a mountain with a temple and views over the Mekong. He wanted to go see it and make her see it too. It was surely feasible. He turned and looked through the open door into the living room, which was now almost dark, the lights of the swimming pool transforming the drawn curtains into a square of dark gold. A wave of nostalgia came over him and he thought of his parents going quietly about their honorable and unrelenting lives in a council house in Bevendean at the edge of the Downs. It was six in the morning there perhaps and his father might well be already in his surprisingly fertile English garden cursing the onset of frost. They ate their porridge together listening to the Today program on Radio 4. He had sent postcards by now to calm them and keep them, as it were, on his side. The postcards would be on the mantelpiece, displayed for some reason. So his disappearance was not yet total and his parents were not yet looking for him and lying awake at night wondering if he was dead. They were maybe worried about him leaving his job and soon the school and his English girl would be dropping by to ask them if they knew anything. They were reticent people who understood the laws of discretion and it was possible they would fend off those questions artfully. He didn’t know. His mother, certainly, would not be convinced by his assurances. She knew how unhappy he was. The first thing that would emerge in her mind when she woke would be her son. Just then, as his eyes were adjusting to the dark and just as he was imagining his mother rising into a cold English dawn, a shadow crossed the gold square and stopped for a moment and seemed to look into the room. Then it moved on and he heard the curious whale-like snorts of the swimmers who always did laps at that hour. He rolled over and his mouth was dry.

“What’s wrong?” Sophal said.

“It’s nothing. I was just thinking about my mother.”

“Does she know where you are?”

“I sent her a postcard—”

She suddenly felt awake again. Did people still send postcards?

“It’s better than nothing, I suppose. If you disappeared tomorrow would you send me a postcard?”

“No.”

“I knew it. I’d use telepathy.”

He thought, Would I really not send one?

They went out later and had dinner at a Viet place called Ngon near the Victory Monument, an open-air place with frangipanis and fans and tables with bowls of spices and stone mortars. They ate bowls of boun with vermicelli and fried nem and chilled coconuts with the tops lopped off. There was nothing more to say for the evening. Finally he did say, as if it didn’t matter and he had not been thinking about it for a while, “You know, I think we should go to Phnom Bayong after all. Your father will approve.”

Along the river an hour later the lamps burned in a soft and solitary splendor, their stationary light enabling the eye to see the motion of the unlit waters below. They walked arm in arm underneath them and from the river came the sweet humidity that raised their spirits and made Sophal want to empty a bottle of vodka. High clouds soared above the city in monochrome, hammer-headed and seeming to swim like sharks upward toward a dimly present moon. At the horizon the pink flashes of lightning silent against the same clouds. There was no rain yet and the young girls sat with their boys in the gloom eating ice creams and watching them pass. The grass sloping down to the river made him dreamy too. He told Sophal about the river his father used to take him boating on. The very evocation of it in words made it materialize anew in his mind, from where it had been absent for a very long time — for a period, in fact, that felt emotionally like centuries. The river, the home country and its dull and heavy memories. The river was called the Ouse and it ran through the Sussex countryside from the village of Piddinghoe down to the sea at Newhaven. And, long ago, his father took him sailing on a small catamaran to show him how. The river ran between mud and chalk banks and in high summer there was a feeling of death and stillness upon it, abandoned tankers rusting in the shallows, the dragonflies playing over it just as they did here. The cemeteries dated from the Middle Ages, from the age of Stephen’s War, “when God and his angels slept.” The river smelled of salt and stewing algae. If only he had known it had been a premonition of Phnom Penh. Both places had an atmosphere of decay but the decay of each was different. The English kind was the sweet torpor at the end of a long and successful innings; it was recent and slightly weary. It was a kind of refusal to live violently and intensely. It was smugly moral. The Khmer decay, on the other hand, was long-standing but the Khmers themselves were quickly emerging out of it. There was no weariness or old age about them. At least that was his way of interpreting it. Perhaps mistakenly. The Khmers didn’t have time to lecture either themselves or others. They were young and wounded, but their wounds were so deep that they could be ignored for a while. Their sadness was of a different kind, too. It was from the 1970s, a time that every fifty-year-old could remember vividly. It was the sadness of generations which had entirely lost their youth for nothing and who had no choice but to forget. The sadness of England, however, lay precisely in her tremendous memory, in her refusal to forget anything. Increasingly, and now definitively, he felt that his affinity lay with the Khmers. They were indefinably alive. In their faces, in their eyes, there was the constant surprise of life itself, that horrifying and sweet wonder. Their ancientness took a different form from his own. It was almost as if it was physical and unconscious, thousands of generations compressed into gesture and speech patterns and quick understandings. They were more subtle than the English, but they were less cerebral. They were more alive, but less consciously joyous or boisterous. For centuries, and even now, the whites wanted to improve them, drag them into a future which for the whites themselves no longer existed. But the project would always fail. The pale ones would never understand the real substance. They floated like boatmen on the surface of the Khmer pond, the glassy, fragile consciousness of this race whom the whites despised and whom the most philanthropic among them subconsciously resented.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Hunters in the Dark»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Hunters in the Dark» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Hunters in the Dark» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.