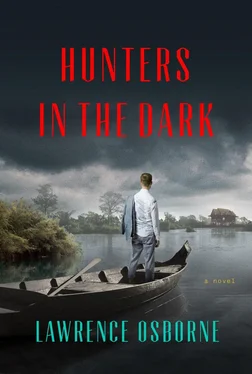

Lawrence Osborne

Hunters in the Dark

To show you mercy is no gain, to destroy you is no loss.

— The Angkar

He came over the border as the lights were about to be dimmed, with the last of the migrants trailing their stringed boxes. With them came gamblers from the air-conditioned buses, returning short-time exiles tumbling out of minivans with microwaves and DVD units. The border forced them all into a defile in the rain. The gamblers complained about their summary treatment while opening plastic umbrellas provided by the tour company. It seemed a shame to them that the casinos on the other side could not manage it better. Their Bangkok shoes began to suffer in the coffee-colored mud. Between the two posts the ground was already filled with pools and the dogs waited for the money. The hustlers and drivers were there, silently smoking and watching their prey. The officer ripped away his departure card in the Thai hut and his passport came back to him and he set off for the farther side lit up by the arc lamps.

The drivers began to wave, to raise their arms and shout, but he could not hear what the words were. Carrying a single bag, he was quick on his feet. He had the aura of poverty about him, but still, he was white and therefore — in their eyes — affluent. He went under the dry eaves of the opposing nation and gave his passport anew to the men behind a shabby window. There were four windows and the men behind did not look very forgiving. They bore considerable weight in their eyes. In the bare concrete rooms, tables were set up with thermos flasks and darkened TV sets. The new king high on the walls in his wise white uniform.

“Tourist,” he said, and they charged him a surplus two dollars for not having a photograph for the visa. He counted out his baht and pushed the filthy money across the table and they stuck a full-page green visa into a page of his passport and tossed it dismissively back at him. He had a month to roam their green and pleasant kingdom and he spent the first minute looking across at the neon lights of the casinos, the dusk and the men waving at him.

The pools opening up under the lamps had grown green as well and he walked gingerly around them with his shoulder bag and his straw hat growing soggy as the rain enveloped him.

“Sir, taxi,” the men were crying, already each one setting off toward a large run-down Japanese car. Forced to pick one at random, he chose a man with a Toyota and an umbrella and it was seven dollars into Pailin. Above them shone the red and blue lights of the Diamond Crown casino. But he was tired and not yet in the mood for a fling on the tables. He resolved to return the following night.

—

He sat in the backseat and drank from the bottle of iced tea he had bought at the border stalls. The verges were filmed red with sticky and wettened dust and in the dark were rolling green hills dotted with primeval-looking, isolated trees. Fields of mung and shaggy sugarcane. It was windy, the sky jagged with storm clouds and a Peeping-Tom moon. The site of a disaster, or of a disaster about to happen. The earth dark with iron and cloying and musty to the nose. He was down to a hundred dollars so he asked the driver to take him to a cheap place for the night, he didn’t care where. Turning his head for a moment, the driver told him there were only two or three choices in the town anyway and none of them was the Hilton. A half hour later they were passing the traffic circles of the town, a few roadside bars with red Angkor beer signs. A small park with twelve golden horses prancing in a grit-filled wind.

The man took him to a place called the Hang Meas. It was on the main road to the border, which was lined by one-story shops. Pailin, to his eye, was clearly a place with three streets and little more. A town built on illegal gemstones and the undeparted Khmer Rouge. A dead and absurd sign on the hotel’s facade read, as if contradicting its current lamentable state, Le Manoir de Pailin. The establishment’s pink walls and the karaoke club on the ground floor gave a further dying look to it — he could tell that it was about to close. There were life-size sculptures of deer on the roof gazing out to the Cardamom Mountains and white glass-ball lamps on the balcony. A huge model cockerel stood in the car park and next to it a spirit house filled with kneeling figures with painted white hair and beards. The ancestors of that windswept place, secretly connected to the fields and the mountains which could be seen even in the night. The car left him by them and he waded into a decrepit lobby with his wet hat and his chills and the girls looked up with a subtle contempt.

He sat in a leather chair by some fish tanks while they photocopied his passport and stamped the forms, and he saw the entertainment hall next door to the lobby with a multitude of red pillars wrapped with ribbons and covered with mirrors. In there the karaoke was going on, Viet or Chinese businessmen singing badly. The girls were in clasped silk skirts playing them for a song. It was a Bee Gees number, “How Deep Is Your Love?”

A girl ambled over and invited him to come with her to the room on the third floor. They went up the stairs and their scents came into awkward contact.

“Holiday?” she said, as if it was the sole English word she had.

“Business,” he said.

It was the word that usually ended all conversations.

“We closed next week,” she said sadly.

They came into the room and the same smell pervaded it. It’s OK, he said, as if there was a choice in the matter. She showed him the workings of a few switches and left him alone. He turned on the AC, stripped off and took a tepid bath with the lights on. One had to fear such a wonderland of roaches. He smoked his last three Thai cigarettes and considered if he had the gall or the energy to go out straight away and find a casino. There would be little else to do here anyway. The other foreigners who crossed the border — nearly all Thai — either went straight back into Thailand or carried on toward the capital, a mere five hours away. They would have to think of a reason to stay in Pailin. He would have to think of a reason other than not having more than a hundred dollars. But it was a reason, at least. He opened his bag and pulled out a cheap dress shirt and pressed it out with the iron in the cupboard. He could make himself half presentable after a shave and an oiling of the hair.

At nine thirty he went down to the lobby and asked them to call a taxi to the gates to drive him to one of the casinos back at Phum Psar Prum. He strolled out in his awkward shirt, his pockets filled with US dollars, and the car was summoned by the boys outside in their “security” uniforms. He said “Casinos” to the car that pulled up, and when he added that he didn’t know which one, there was a confusing consultation. In the end he was driven to the towering place he had seen an hour or two earlier, the Diamond Crown. It was a pointless forty minutes driving there and back again, but he didn’t mind. Anything was better than karaoke or an empty room.

The Diamond loomed over the village around it. There was a forecourt garden of towering palms, and a blaze of neon across the facade in Latin and Khmer lettering. Outlines of playing cards and golden women. A KTV to the right, and a hotel of the same name. Inside, red carpets, sky-blue vaults with painted clouds. There were Chinese shrines; a tacky, run-down feel. The tables were green felt. The Khmer girls in their equivalent green waistcoats watched him slowly with a dim interest. In one corner two staff workers struggled with a large rolled carpet. It was a hot crowd, mostly Thais playing simple poker and baccarat and roulette. They looked like officer workers on a lost weekend. He walked around sizing it up and wondering if he had luck on his side that night, or ever, for that matter. Finally he sat at a drunken table and played roulette for five-dollar bets against a ring of Thai middle managers downing the Sang Som and Yaa Dong and far gone in their daze. There was no time to calculate or think and later he thought to himself that this was how he had won. It’s how an outsider always wins. He pulled in two hundred, packed up and went outside to buy some Alain Delons. At the far end of the forecourt was an outdoor restaurant filled with half-dead gamblers and he sat there and smoked and saw that the moon had appeared again out of the fast-moving black storm clouds.

Читать дальше