“You can take me down to the city,” Davuth said to the drunk now, “and I’ll pay you what the American pays.”

Thy looked away and into his dirty ice as if mention of the American was mysterious bad luck.

“He pays better than anyone.”

“Yeah, well, I’ll pay the same.”

It was a deal and Davuth asked him sternly if he was sober.

“Of course I’m sober,” Thy said defiantly.

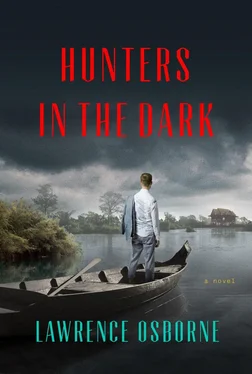

They went down to his boat tied up at the jetty and set off with the sun at their backs. Davuth sat next to him in the cabin and they chatted with rum and cigarettes and Thy told him all about the young barang he had taken down to the city a short while ago.

“How about that American?” Davuth asked. “I heard about him. Wasn’t he some drug dealer down here?”

“He was but he took off. I heard—”

Thy’s face tightened and he glanced down at the hands of the policeman, which were resting passively but somehow dangerously in his lap.

“You heard what?”

“I heard they fished him out of the river.”

“They did?”

“He must have crossed the drug dealers in Pailin.”

“I guess he must have.”

“It’s not a smart thing to do.”

“It’s the stupidest thing to do, all right. But you had a few dealings with him. Tell me about him.”

“Why?”

“I’m just curious. I heard a lot of stories.”

Thy was now drinking heavily. There was a chance, surely, that they would capsize at some point but it couldn’t be helped. Davuth poured out the booze and Delons.

“He was a dealer, I’m sure. But I liked him. He was all right. He paid me good. You can’t ask more than that.”

“No, you can’t ask more than that.”

“He paid me for odd jobs. Between you and me—”

“Yes?”

“A few drop-offs, you know — that kind of thing.”

“I see.”

“Yeah, it was all right. He wasn’t a tightfist.”

“You can’t ask more than that.”

“You bet you can’t. He paid dollars.”

Davuth said that that was the best a man could hope for: dollars with no questions asked.

“You got that right,” Thy said.

“And that British boy you took down to the city—”

“Ah, he was a queer one.”

“Why so?”

“Slept most of the way. Maybe he was stoned when we loaded him on the boat.”

“You and the American?”

“Yes.”

“Why would you do something like that?”

The boatman looked over at Davuth and his eyes went blank.

“Don’t ask me!”

“How strange,” Davuth drawled. “Did the kid know where he was going?”

“He seemed to have no idea.”

“I’ll be damned—”

“He just got off at the jetty where the American told me to let him off.”

“Then take me to the same place.”

“You said you’d pay the same.”

“It’s a promise.”

They drank a fair bit more on their way to the jetty. Somehow the day had passed altogether by the time they got there and the lights had come on in the waterfront shacks and birds swarmed the mulberry trees with a deafening chirping and fluttering. Davuth paid and they went together up to the bank, the boatman staggering and mocking himself, and Davuth took his leave brusquely and went in among the drivers who were hanging out under the babbling trees. He sifted through them asking about the English boy and seeing if any of them remembered him. Since there were very few of them it didn’t take long for him to find the one who had driven Robert into Phnom Penh. Davuth took him to one side and used all his matey charm on him. He offered a pretty good tip if the man could take him to the same hotel he had taken the young barang to.

“Sure,” the man said cheerfully. “It was the Sakura, if I remember correctly.”

“Then let’s go to the Sakura.”

—

It was a chaotic drive. The road was clogged with long-distance trucks. The dusk came upon them. The man chatted glibly. Davuth listened to the stories about his family and then casually asked him if he had noticed anything odd about the young barang he had taken to the Sakura that night. The driver caught Davuth’s eye in the rearview mirror and he wondered if the barang had contracted a debt he couldn’t pay. The man in the backseat looked like a genial enforcer. The driver prevaricated and then admitted that he couldn’t remember much about the foreigner except that he looked quite broke.

“I see,” Davuth said quietly. “But he paid you all the same?”

“He did pay me. He paid twice what you paid.”

They laughed. Davuth leaned over and passed another two dollars to the man. When they came into the city the driver remembered that it had not been the Sakura after all but the Paris on Kampuchea Krom. When they got there Davuth asked him again about the Englishman and the driver said he had had no bags with him. It was an extraordinary thing. A barang with no bags.

Yes, Davuth said to him, it’s an extraordinary thing. With that, he turned and walked boldly into the lobby of the Paris, ignoring the drivers outside. The two girls on duty at the reception desk looked up with an instinctive alarm. Davuth gave off an energy that commanded alertness and wariness, if not a slight distaste that the person seeing him for the first time could not quite pin down. A briskness in the hands, a crisp gait that was nevertheless rarely hurried. He never put women at ease. He set down his bag and smiled, however.

“I’d like a room,” he said.

One of the girls took him up to the fifth floor.

“Have you been here before?” she asked him as they climbed the stairwells. On the higher landings the dolled-up girls parted for them sullenly.

“I don’t come down much to the city these days. My daughter’s at school and I never have the time.”

“Lucky you.”

“She’s a lovely girl.”

“Here on holiday?”

“Business.”

“Ah, I see. Business…”

They came to the fifth-floor landing and its row of tarnished doors and smell of ashtrays, and as they went down it he said, “Did you have a barang staying here recently? A young kid named Robert?”

She stopped and their eyes met in the semi-gloom near an exit light.

“No, I don’t think so.”

“Maybe that wasn’t his name.”

She took out the key and continued walking to the door, which she opened quietly.

“Maybe it was Simon, his name.”

“I don’t remember all the names,” she said.

“You have a lot of young guys staying here for the girls?”

“All ages.”

“But not a lot of young barangs?”

“A fair number. They like the girls too.”

Davuth smiled.

“So it’s rumored. But you’d notice a good-looking young one.”

He closed the door behind them and threw his bag onto the bed. He went up to her and passed a ten-dollar bill into her hand.

“He hasn’t done anything wrong,” he said. “I just want to know if he was here.”

She nodded and absorbed the bill.

“Which room?”

“The one next to this.”

“Can I change rooms?”

She hesitated. “I think there might be someone in there.”

They listened, and the comical nature of the pause made them both smile. An old Chinese guy getting off with one of the spinners?

“I think it’s empty,” she said. “Let me call down and check.”

When she had done so she took him next door to the other room and let him in. He threw his bag onto the bed a second time and strode to the windows, pulled open the curtains and looked down at the boulevard alive in its evening glory. The trees glittered with a golden light. The KTV was lit up. One forgot how both Chinese and French parts of the city felt as night fell. He thanked the girl and asked her again if she remembered anything about the barang occupant of the room and then asked her, in a different tone, if she wouldn’t mind keeping this all between them. He assured her that there was no sinister reason for his asking this. It was just discretion, which benefited everyone. She agreed and he watched her slip away with a malicious satisfaction in the power of ten-dollar bills. Then he locked the door and set to searching the room on his hands and knees.

Читать дальше